“Soil type is what we were really going for – having good, workable soil. We fell into a market that received us well, but we didn’t move here for that. It was really just for the 25 acres of great soil.”

– Spencer Blackwell

Background

Spencer Blackwell started farming when he was an undergraduate student at the University of Vermont. At the time, he worked for vegetable growers in the University’s home city of Burlington. After graduating, Spencer continued farming. After 10 years of working on various farms around the state of Vermont, he started his own venture at the Intervale, an incubator farm in Burlington, Vermont.

Starting at the Intervale

The Intervale leases land, equipment, and infrastructure to small independent farms. The goal of the Farms Program on the Intervale is to remove start-up barriers that typically challenge new farmers, such as access to land, training, capital, markets, and equipment.

Once on the Intervale, Spencer noticed that almost all farmers there were growing vegetables. He concluded that he should differentiate himself by focusing on small grains, like dried beans. During his time on the farm incubator, Spencer enjoyed the opportunity to learn from fellow farmers about soil quality and growing crops. He also appreciated the ability to share farm equipment without having to purchase it (although he noted that people who don’t know how to use equipment properly can damage it).

However, during his time on the Intervale, he began to feel that he might be better suited somewhere else. First, he felt that Burlington wasn’t his “scene.” Second, he was concerned about the lack of opportunity to gain equity in the land and to build needed infrastructure. He was also turned off by some of the interpersonal politics related to collaborative farming, where everyone has a stake in the land. Ultimately, Spencer began looking for land of his own to purchase.

The Pursuit of Land

In looking for his own piece of land, Spencer had two priorities: soil quality and cost. “Soil type is what I was really going for,” he said, “having good, workable soil.” Ultimately, after approximately 20 visits to potential properties, he and his wife Jennifer found 89-acre Elmer Farm in Middlebury, Vermont.

Spencer and Jennifer found Elmer Farm through Vermont Land Trust’s (VLT) Land Access Program. The program is designed to provide farmers with opportunities to purchase or lease affordable farmland. To achieve this goal, VLT connects farmers with farms as they come on the market, purchases conservation easements on farm property to make land more affordable, and expands farm leasing opportunities.

After seeing Elmer Farm, the couple knew they wanted the property. It had more than enough land, it had the right soil quality, and it was the right price. However, closing the deal wasn’t as simple as saying “yes.” “VLT has a vision of who they want the buyer to be,” Spencer explained. To participate in the Land Access Program, VLT requires that candidates have at least three years of farming experience, strong agricultural references, plans to develop an agricultural enterprise that would gross $100,000 annually within five years, and sufficient financial resources for start-up costs. Ready to make the purchase, Spencer and Jennifer submitted the required proposal to VLT, which then selected them to be the next farmers of the Elmer land. “They thought that what we were trying to do was most suited to the community,” Spencer said.

As part of the purchase negotiation, VLT retained a conservation easement and an option to purchase at agricultural value (OPAV) on the land. The conservation easement includes terms aimed at preserving the property. For example, it includes provisions that:

- Prevent the property from being developed for non-agricultural purposes;

- Protect the surface of the land from excavation, topsoil and other mineral removal, and mining of oil, gas, or other minerals; and

- Prohibit the land from being subdivided or conveyed in separate parcels.

Specifically, one provision of the easement states that:

“No residential, commercial, industrial, or mining activities shall be permitted, and no building, structure, or appurtenant facility or improvement shall be constructed, created, installed, erected, or moved onto the Protected Property, except as specifically permitted under this Grant. The Protected Property shall be used for agricultural, forestry, educational, non-commercial recreation, and open space purposes only.”

The easement also provides Spencer and Jennifer with certain agricultural rights such as the right to:

- Establish, maintain, and use cultivated fields, orchards, and pastures in accordance with generally accepted agricultural practices;

- Conduct maple sugaring operations on the property;

- Use, maintain, establish, construct, and improve water sources, courses, and bodies within the property; and

- Use all-terrain vehicles on the property for the purposes of agriculture and forestry.

The easement also includes a forest management plan, enforcement mechanisms, and the Option to Purchase at Agricultural Value mentioned above. An OPAV can be sold by a landowner to a conservation organization or the government. It allows the holder (buyer) of the OPAV to purchase the land at agricultural value if the landowner offers the property for sale to anyone other than a family member or a qualified farmer. The OPAV that VLT holds on Elmer Farm spells out to whom Spencer and Jennifer may sell, convey, or transfer the property, what will trigger the OPAV, and how to calculate the agricultural value of the property. Additionally, there is a separate walking trail easement on the Elmer Farm property that is owned by the Middlebury Land Trust.

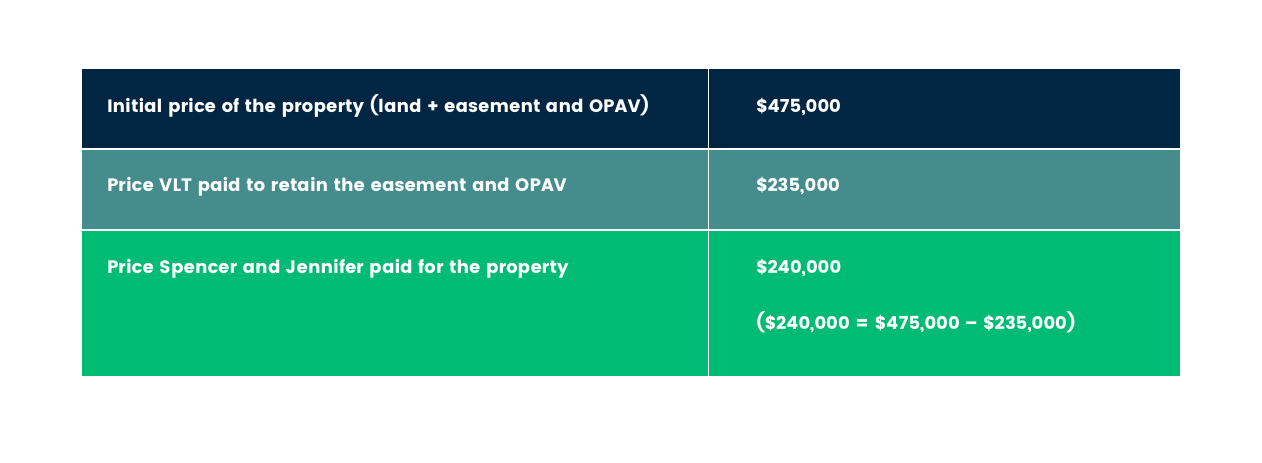

Because Spencer and Jennifer planned to operate Elmer Farm as a certified organic farm with ecological and sustainable values, they felt that the conservation easement would not impede their farming business. However, Spencer and Jennifer still had to negotiate certain elements of the easement. For example, there was some back and forth on drawing easement lines. Specifically, the Middlebury Land Trust wanted a larger easement for the walking trail than Spencer and Jennifer were willing to provide. Spencer and Jennifer also negotiated regarding price. VLT initially offered the property for $270,000, which included the right to build a second building on a portion of the property where it otherwise would have been restricted by the easement. Spencer and Jennifer had no plans to build, but didn’t want to write the option off, so the parties compromised: Spencer and Jennifer purchased the farm for $240,000, relinquished the right to construct the second building, but retained the right to repurchase those development rights. Below is the breakdown of the property price:

In order to pay the $240,000 purchase price, Spencer and Jennifer secured private financing through a family member. Spencer describes his biggest challenge along the way as “just finding the land – finding good quality soil at an affordable price.” He goes on to explain that there isn’t a lot of good land available at any price. “Farmers that are profitable know the value of good land and aren’t giving it up – even for development.” In fact, Spencer and Jennifer almost lost the farm to higher bidders. Luckily for Spencer, the Elmers – the farmers who sold the property to him and Jennifer – had philosophical goals in putting their property on the market. Namely, they were interested in keeping their farm sustainable. As a result, when the Elmers’ neighbors offered considerably more than Spencer and Jennifer for the property, the Elmers declined the offer because the neighbors farmed using conventional methods that didn’t meet the Elmers’ stewardship goals.

When asked what his hopes are for the future of Elmer Farm, Spencer jokes, “I hope that the vegetables can walk up the hill themselves!” On a more serious note, Spencer says he hopes that “we can reduce our inputs and grow high quality, nutrient dense vegetables without as much effort as when we started.”