Wills

Overview

Overview

A will is a legal document directing how your assets will be distributed after death. To ensure farm transfer goals are met, a will can generally be used in combination with, at least: one or more types of trusts, long-term health care planning, life insurance, and tax planning for both estate taxes and gift taxes.1

Using a will as part of the farm transfer process will require a public “probate” process that involves a court, can take at least 12-18 months, and generally requires the help and expense of an attorney who specializes in probate law.

Creating an effective will and farm transfer plan that actually does what you want it to do will almost always require the help of an estate planning attorney. Estate planning attorneys can draft wills, set up trusts, help keep farmland in the family, help find tax advantages, and help determine the best combination of legal tools to meet strategic farm transfer goals. If possible, it’s best to find an estate planning attorney who has experience working with farmers and understands the special rules and benefits that apply to farms.

Farmer Spotlight:

Wahi Ranch

The Wahl family has been raising sheep and cattle in Oregon since 1874. Their 2,000-acre ranching operation includes timber-producing forests, ponds, riparian buffer vegetation, and wetland habitats.

What Is A Will?

A will is a plan that someone makes giving instructions about how they want their property (assets) to be distributed when they die. Wills can be highly individualized according to each farmer’s situation, and can include special provisions to help children continue the family farm business. A will can also help farmers thoughtfully distribute assets among multiple children—including some who don’t want to farm (non-farming heirs), and some who do want to farm (farming heirs). If a farmer is married, the farmer and the farmer’s spouse should each have a separate will.

Wills often include:

- Appointment of a trusted personal representative (also known as an “executor”) to handle the estate, collect assets, pay debts, and manage the distribution of assets according to the instructions in the will;

- Procedures for distributing property;

- Special mention of how the spouse will be treated under the will;

- Special mention of how children will be treated under the will;

- Incorporated trusts (often called “testamentary trusts”) to help avoid estate taxes and protect the spouse and/or children;

- Special provisions to help farming heirs remain on the farm;

- Any instructions on who should not receive any property; and

- Provisions for the care of minor children.2

If a farmer dies without a will, state law determines how the farm property will be distributed. A person who dies without a will dies “intestate.” Dying without a will is risky, because state law will not account for farm transfer goals. For example, farmland may have to be put up for sale instead of being passed to a farmer’s child who wishes to maintain a family farm legacy. In addition, dying without a will is likely to create heirs' property, which creates a whole other set of problems for maintaining the land.

What is Estate Planning?

Estate planning (also referred to in the farm transfer context as “succession planning”) is the process of strategically controlling your assets during your life and strategically distributing your assets after death. Important estate planning goals are: 1) Ensuring you have the necessary income and resources upon which to live; 2) Ensuring that upon your death, your assets go to the people and/or organizations you intend; and 3) Minimizing estate taxes, fees, delay, disputes, confusion, and associated court costs.

Estate planning involves setting goals and using legal tools and strategic planning to meet those goals. A will is a key part of an estate plan. Your will (and/or trust) should be tailored to meet your farm transfer goals. Property, farm business ownership, and the transition or distribution of such assets should be examined and tailored to your farm transfer goals. Estate liquidity issues (being able to acquire cash quickly) should be reviewed and can sometimes be addressed with the help of life insurance. Family income requirements should be matched with projected income. Other issues to be considered include treatment of heirs (farming and non-farming), incapacity planning through the use of powers-of-attorney and health care directives, disability planning, tax planning, personal representative or trustee selection, estate administration cost savings, long-term health care issues, and more, depending on your personal situation.

Estate planning can be a simple or complex process depending upon the size and composition of your estate, your family situation, and your business situation. No two families have precisely the same set of circumstances. Farm families, however, tend to have more complex estates and goals. Effective estate planning for farmers requires the help of an estate planning attorney, preferably one that has experience working with farmers. Without legal help, specific farm transfer goals are unlikely to be met. Investing in strategic estate planning up front is often far less costly and disruptive to a farm family than handling these issues after a disability or death.

How Wills Work

How Wills Work

Most farmers should seek the assistance of an estate planning attorney in order to create a will that follows all state requirements, to meet farm transfer goals, to design a plan to minimize estate taxes, and to avoid heirs' property. Often, farmers have somewhat complex estates because they own complicated assets, such as farmland, a farm business, farm buildings, livestock, equipment, and may want to keep these assets undivided and under family ownership. Complex estates require more complex wills, and often benefit from the use of one or more types of trust in conjunction with a will. Sometimes a trust might be created by and incorporated into the will itself.

Wills should be kept in a safe place, like a fireproof safe or a safety deposit box, and your personal representative and heirs should know where the will is kept. Additionally, if you would like to make changes to a will, it is important to make those changes formally and in writing—usually with the help of an attorney. Without taking formal steps, any changes you may want to make might not actually take effect at death.

Making a will legally effective after death most often requires a court-supervised probate process, described below. While probating a will has the benefit of a court’s approval and enforcement, many farmers try to avoid it (if possible) because it can be an expensive, lengthy, and public process. Avoiding probate generally requires using a specific type of trust to transfer assets. Trust creation and administration also requires the assistance of an experienced estate planning attorney.

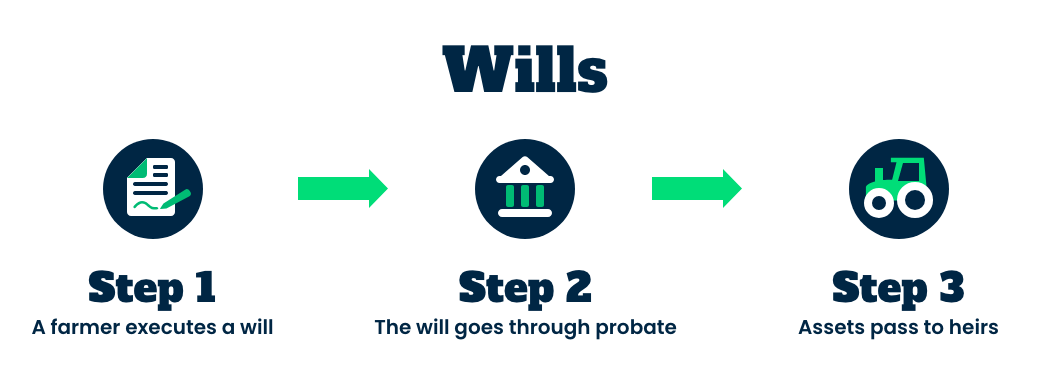

A will is equivalent to a letter of instruction to the court system that automatically starts a probate process when the testator (the will creator) dies. Probate is the process in which a court recognizes that a will is valid, decides who will be the personal representative for the testator’s estate, establishes clear title (ownership) of any assets, and approves the plan for distributing the assets.

Probate is a public process, and can be time consuming (12-18 months, or more) and costly (attorneys may charge an hourly fee, or a percentage of the value of the estate, such as 2% to 3%). (Probate is less expensive for people with properly drafted and executed wills.) The purpose of probate is for the court to make sure the testator’s (will creator’s) assets are managed and distributed effectively and according to the testator’s wishes as set forth in the will.3 It also ensures that the testator’s tax obligations and debts are paid off before distributing the assets according to the will's instructions. Assets that are subject to the probate process are any assets in an individual’s name that are not otherwise able to be transferred at death through some other mechanism, such as a beneficiary designation (a retirement account, for example) or joint ownership of the asset (such as certain joint bank accounts with a right of survivorship so that the survivor is automatically entitled to the funds). Assets that are jointly owned by the individual who died and others, if there is no right of survivorship, are subject to probate up to the amount of the decedent's ownership. Assets that are not subject to the probate process are called non-probate assets.4 The probate process can be avoided in some instances, at least in part, when farmers strategically use a certain type of trust (like a Revocable Living Trust) to transfer assets at death.5

Probate Process Steps

Although the process of probate differs depending on state law and the individual's circumstances, there are generally eight steps (described below).6 Prior to beginning the probate process, the decedent’s (will creator’s) personal representative or the decedent’s heirs will need to locate the will itself, consult with a probate attorney, and obtain copies of the death certificate.7

- Individuals who want a court to enforce or invalidate a will file a petition with the court. Generally, the proposed or nominated personal representative will file the petition (often with the help of an attorney).

- The court then appoints the personal representative.

- The court determines the validity of the will.

- The personal representative collects and takes inventory of the decedent’s (will creator’s) assets.

- Depending on state law, if the decedent had a living spouse or minor children, the spouse or minor children may be entitled to certain allowances that take precedence over certain debts, creditors, and obligations of the estate.8

- Creditors are then paid off. The decedent’s creditors are paid from what remains after a surviving spouse or children are given any property required to be distributed to them.

- The decedent’s assets are then distributed according to the instructions of the will.

No Valid Will At Death = Dying “Intestate” = State Law Controls Asset Distribution

If a person dies without a will, or if a will does not meet state requirements for being valid, then assets pass through intestate succession, meaning that state laws and/or state courts determine who gets what property. Each state has enacted its own intestate succession laws.10

State rules on how property is transferred cannot take into account an individual's desires or individual circumstances. So, those rules can differ dramatically from what a farmer really would have wanted to happen to their property. Even where it is known what a farmer might have intended under a farm transfer plan, if there is no valid will, state law governs. There are no exceptions made based on need or special circumstances.11

Finally, if you have multiple heirs, dying without a will means your heirs will inherit the property as tenants in common. This is the most vulnerable way of holding land, and can lead to loss of the land, or the inability to generate wealth for successive generations from the land. Please review the pages on this website describing heirs' property and the difficulties of owning land in this way.

Farmers likely have particular goals for farm transfer that are not likely to be met by state intestate succession laws. That means it is important for a farmer to have a will drafted by an attorney.

How Wills Relate to Farm Transfer

Farmers can use a will to make sure the farmhouse, farm business, farmland, farm equipment, and any other farm assets go to intended people or organizations. People inheriting the land can be within or outside the family.

Pros and Cons

Pros and Cons

Advantages for Senior Farmers (Will Creators)

Advantages for Senior Farmers (Will Creators)

- Wills drafted by an estate planning attorney can help ensure farm transfer goals are met, and can create and incorporate trusts and other tools (like power of attorney, health care directives, etc.) as necessary.

- Wills are generally easier, and thus less costly, to arrange than a trust.

- Wills generally require a probate process. Although probate involves time, cost, and court intervention, if a will is drafted and executed properly, probate can be less expensive and quicker than not having a will at all. Also, the probate process can be helpful in situations where the heirs may not agree on the will’s instructions for distributing assets. It also insures that the title to the land transfers appropriately to the correct people, rather than remain in the name of the person who died. Finally, the will should name an executor, who is in charge of the distribution of the assets alongside the probate court.

Disadvantages for Senior Farmers (Will Creators)

Disadvantages for Senior Farmers (Will Creators)

- The transfer of property under a will only occurs upon the death of the farmer. In contrast, some types of living trusts (and other mechanisms, like LLCs) can be used to gradually transfer property during a farmer’s life. Wills can be used in addition to trusts and other farm transfer tools.

- Wills must generally go through the probate process. Probate can be expensive and lengthy, meaning there may be a delay in transferring the assets. Furthermore, probate is a public court proceeding, which may make farmers and heirs uncomfortable.

Advantages for Junior Farmers (Potential Heirs)

Advantages for Junior Farmers (Potential Heirs)

- A will, especially if used as one tool in a strategic estate planning process, can protect farming heirs and allow the farm business to be passed on.Without a will, state law governs, and could make preserving a family farm legacy impossible.

Disadvantages for Junior Farmers (Potential Heirs)

Disadvantages for Junior Farmers (Potential Heirs)

- The probate process can cause interruption of the farm business, potentially resulting in financial and other losses.

- A will that is not designed with farm transfer goals in mind could result in family discord and the inability to pass on the farm.

How An Attorney Can Help

How An Attorney Can Help

The Attorney’s Role

It’s not an attorney’s job to make decisions for farmers or to set farm transfer goals. Instead, attorneys can provide information about pros and cons of different options, advice about what is common versus unusual, fair versus unfair, etc. Attorneys can help farmers understand the universe of possible farm transfer goals and help narrow down individual options so that farmers can make final decisions.

How An Attorney Can Help With Wills

- Help draft a valid will that meets farm transfer goals. Using an experienced attorney can help assure a farmer that their assets will be distributed according to their wishes.

- Incorporate trusts into a will, or into a farmer's overall estate plan. Using trusts in combination with a will can help ensure an uninterrupted transfer of a farm business to a farming heir.

- Reduce farmers’ estate tax obligations.

- Probate attorneys specialize in helping families through the probate process, and can help make that process go smoothly.

- Attorneys can also help farmers use wills as part of a larger strategic estate planning process that incorporates long-term health care planning, life insurance, health care directives, power of attorney decisions, and more.

Additional Resources

Additional Resources

- Transfer and Estate Planning, University of Minnesota Extension.

- Iowa Farmers Business and Transfer Plans, Iowa State University Extension

Related Legal Tools

Footnotes

1. Gary A. Hachfeld, et. al., Establishing A Will, University of Minnesota Extension Estate Planning Series (2016), https://extension.umn.edu/transfer-and-estate-planning/gifting-farm-assets

2. Each state has its own rules governing how to create a valid will. Generally, a will must be in writing and must be signed. The signing of the will must be observed by a usually at least two witnesses. See, e.g., Uniform Probate Code s. 2-502 . For example, in Ohio, a will is valid if it is made by someone who is at least 18 years old, it is in writing (typed or handwritten), it is signed by the person creating it (or on behalf of him/her), and signed by two witnesses within the will-creator’s conscious presence (meaning within any range of the will-creator’s senses). See Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 2107.03. Depending on the state, a court may accept a will that does not follow all of the requirements. Furthermore, about half of the states treat as a valid will documents that do not follow the state’s requirements but are in the will-creator’s handwriting with the will-creator’s signature (known as a “holographic will”). Some states such as Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Massachusetts, Mississippi, Missouri, New Hampshire, and more even allow for oral wills in limited circumstances (known as a “nuncupative will”).

3. Gary A. Hachfeld, et. al., Establishing A Will, University of Minnesota Extension Estate Planning Series (2016), https://extension.umn.edu/transfer-and-estate-planning/gifting-farm-assets; see also Cort A. Neimark, Helping Your Clients Understand The Probate Process and Meeting Your Client’s Expectations, The Role of Probate Court in Administering Estates, 2012 WL 2165919 at *1.

4. Gary A. Hachfeld, et. al., Estate Planning Principles, University of Minnesota Extension Estate Planning Series (2016), https://extension.umn.edu/transfer-and-estate-planning/gifting-farm-assets.

5. Gary A. Hachfeld, et. al., Revocable Living Trusts, University of Minnesota Extension Estate Planning Series (2016), https://extension.umn.edu/transfer-and-estate-planning/gifting-farm-assets.

6. For a Florida example, see “Step By Step Guide To The Probate Process,” The Law Offices of Snyder & Snyder, P.A., http://www.snyderlawpa.com/global_pictures/stepbystepguidetoprobateprocess.pdf.

7. Gary A. Hachfeld, et. al., Steps in Estate Settlement, University of Minnesota Extension Estate Planning Series (2016), https://extension.umn.edu/transfer-and-estate-planning/gifting-farm-assets.

8. See, e.g., Notice to Spouse and Children, State of Minnesota, Ramsey County, https://www.mncourts.gov/mncourtsgov/media/CourtForms/PRO906.pdf?ext=.pdf

9. See Trav Baxter, Succession Planning for Family Farms, Ark. Law., Fall 2015, at 18, 20, https://issuu.com/arkansas_bar_association/docs/lawyer_fall_2015_issuu/20.

10. See, e.g., Understanding Intestacy: If You Die Without An Estate Plan, Findlaw, http://estate.findlaw.com/planning-an-estate/understanding-intestacy-if-you-die-without-an-estate-plan.html.

11. Understanding Intestacy: If You Die Without An Estate Plan, Findlaw, http://estate.findlaw.com/planning-an-estate/understanding-intestacy-if-you-die-without-an-estate-plan.html.

The Center for Agriculture and Food Systems is an initiative of Vermont Law School, and this toolkit provides general legal information for educational purposes only. It is not meant to substitute, and should not be relied upon, for legal advice. Each farmer’s circumstances are unique, state laws vary, and the information contained herein is specific to the time of publication. Accordingly, for legal advice, please consult an attorney licensed in your state.