Collaborative Farming

Overview

Overview

Farming collaboratively allows farmers to pool resources and work together for mutual benefit. It requires cooperation, compromise, and trust.

This page will cover some of the pros and cons of collaborative farming, and will also provide brief descriptions of some types of arrangements that farmers can use to pool resources and work together – either formally or informally. Ultimately, though, every collaborative farming arrangement is unique and varies depending on the needs, wants, personalities, resources, and capabilities of the farmers involved.

Within the descriptions below, you will also find links to real-life farmer stories illustrating examples of collaborative farming arrangements.

Farmer Spotlight:

Urban Edge Farm

Managed by Southside Community Land Trust (SCLT), and based in Providence, Rhode Island, Urban Edge Farm is an incubator farm that helps aspiring farmers start their own enterprises. An incubator farm is designed to give new farmers access to affordable land, equipment, tools, infrastructure, and established markets. This helps new farmers learn the art of farming and create their own brand. If a farmer flourishes, they can leave the incubator, find their own land, and start their own business. Alternatively, if a farmer decides that farming is not for them, they can walk away with minimal investment. Click here to learn more about Urban Edge Farm, and read on for more information about incubator farms.

Pros and Cons of Collaborative Farming

Pros and Cons of Collaborative Farming

Resource sharing for mutual benefit is one of the main advantages of collaborative farming arrangements. Shared resources could include the following:

- Skills

- Knowledge of farming practices

- Labor

- Equipment

- Infrastructure (for example: barns, greenhouses, or hoop houses)

- Land

- Costs

- Marketing and distribution plans and activities

- Pack houses or processing facilities (and labor)

- Sales

- Business plans

- Farming and business networks

- Energy and support

Although farming collaboratively does have benefits, it also has some potential disadvantages. Farmers should keep these in mind, including:

- Potential for disputes among collaborators

- Profit sharing (especially when money is tight)

- Personality conflicts

- Unequal effort, labor, or resources (real or perceived)

- Lack of shared expectations around money, management, or future farming plans

- Difficulty leaving a collaborative arrangement

- Shared customer base may be split (or may be taken over by one collaborator) if the collaboration collapses

- Potential liability for the actions of collaborative business associates, especially if sharing profits

- Lack of sole control over your farm business

- Different ideas about farming practices or marketing strategies

It’s best to weigh the potential advantages and disadvantages of any particular collaboration opportunity before making a serious commitment to collaborate. Many farming collaborations begin informally before transforming into a serious legal commitment (like a formal business partnership or LLC—see more about these below).

The examples below are designed to help farmers get a sense of potential collaborative farming opportunities.

Types of Farm Collaborations

Types of farm collaborations include informal arrangements, incubator farms, lease agreements, and legal business arrangements like legal cooperatives, LLCs, and formalized partnerships. While the types of farm collaborations discussed below are examples of farming collaboratively, these examples are not an exhaustive list of the ways farmers can share resources and work together for mutual benefit. Farmers are continuously finding new and creative ways to support each other and work together.

For best results, before entering any type of collaboration, it’s important to get to know potential collaborators. Collaborators should add value to your operation and should generally have similar farming values and goals.

It’s also essential to plan for the end of the collaboration at the very beginning of the arrangement. Nearly all collaborations will eventually end (whether on good terms or bad terms). Thus, collaborators should plan at the outset for a future exit that is fair for all participants and doesn’t unduly harm individual farm business prospects. This kind of “exit planning” can be informal, but it is often best to put it in writing – especially if you are legally bound to your collaborators (via participation in a lease or business entity, for example). A lawyer can help you draft an appropriate collaboration agreement or help you put exit planning language in your lease or LLC operating agreement.

Informal Arrangements

Informal arrangements are probably the most common type of collaborative farming. Farmers often work together with their neighbors on an informal basis. For example, the three farms on Copake Agricultural Center have no formal agreement and all have separate farming businesses. Still, they farm collaboratively in the sense that they are friends and neighbors who help each other. The farmers on Copake Agricultural Center intentionally decided to forego a formal collaborative arrangement. That means they have no written documents that detail a collaborative model or even an equipment-sharing schedule. Nevertheless, the farmers there often share skills and resources by helping each other fix structures (like hoop houses), meeting to discuss farming practices, and sharing and purchasing equipment together.

An informal arrangement between farmers has the advantage of a “no-strings-attached” collaboration, meaning that all the farmers involved are free to collaborate – or not – as they see fit. However, the downside to this style of arrangement is that you cannot necessarily depend upon help being available when you need it. You may run the risk of becoming a default general partnership if you share profits and losses with informal collaborators. Also, such informal collaboration does not provide much security, whether for the farmer or for a farmer seeking financing from a bank.

Incubator Farms

Incubator farms help aspiring farmers start their own enterprises. Incubators generally operate as collaborative arrangements overseen by an umbrella organization (often a nonprofit that owns the land and manages the incubator). Farmers on incubators typically run separate and distinct farming businesses but share land, equipment, infrastructure, skills, and knowledge of farming practices. The land, infrastructure (like farm buildings, packing facilities, or commercial kitchen space), and equipment are most often owned by the incubator farm itself, and may be leased or offered to farmers who participate in the incubator program.

Farm incubators exist to help remove start-up barriers that challenge new farmers, such as access to land, training, capital, markets, and equipment. Although each one is different, farm incubators typically provide new farmers a combination of the following resources:

- Access to affordable land;

- Access to equipment, tools, and infrastructure such as hoop houses and greenhouses;

- Mentorship and training from experienced farmers;

- Business planning support; and

- Access to established markets.

Starting a farming business on a farm incubator allows new farmers to learn necessary farming skills, experiment with different crops and farming practices, and test the viability of their business ideas without having to spend a significant amount of money on startup costs. After spending time on the farm incubator, if farmers decide not to pursue their business further, they can wind down the enterprise with fewer losses than they might have incurred if they had had to start up on their own. Alternatively, farmers can leverage the training, experience, community exposure, and market share gained on the incubator to later create a successful farming business off the incubator site.

Farmer Spotlight:

From Incubator to Farm Ownership: Elmer Farm

Spencer Blackwell began his farming career on an incubator farm in Burlington, VT. During his time on the farm incubator, Spencer enjoyed the opportunity to learn from fellow farmers about soil quality and growing crops. He also appreciated the ability to share farm equipment without having to purchase it (although he noted that people who don’t know how to use equipment properly can damage it).

However, during his time on the Intervale Center, he began to feel that he might be better suited somewhere else. He felt that Burlington wasn’t his “scene.” Spencer was concerned about the lack of opportunity to gain equity in the land and to build needed infrastructure. He was turned off by some of the interpersonal politics related to collaborative farming, where everyone had a stake in the land. Ultimately, Spencer began looking for land of his own to purchase, and he and his wife Jennifer now own Elmer Farm. Read more about how the Blackwells found their farm here.

Additional farmer stories within this toolkit related to incubators include Pine Island and Digger’s Mirth.

Pros and Cons of Farm Incubators

Pros and Cons of Farm Incubators

Advantages of farming on an incubator include affordable access to land, an instant farming network, a repository of shared knowledge, and emotional support for the ups and downs of farming. While starting a farming business on a farm incubator has many benefits, it also has some drawbacks that an aspiring farmer should keep in mind.

Lack Of Control Over Access To Specific Farming Plots Within The Incubator Farm Property

- Farming on a farm incubator generally does not allow a farmer to shop for soil quality or land placement. For example, a farm incubator may have fields located in a flood plain or may not have the type of soil best suited for the crops a farmer would like to grow.

Challenges In Equipment Sharing And Maintenance

- Sharing equipment with new and beginning farmers means that the equipment will have the typical wear and tear associated with use by many people (and often people who are inexperienced at handling machinery.)

Required Paperwork

- Most incubator farms require a business plan proposal and application process, and while it is wise to have a well-developed business plan, plans and paperwork add a level of complexity and administrative burden for busy farmers.

Difficulty Leaving The Incubator

- Moving off of the incubator can be costly or impossible because land and transition costs are high. Furthermore, even if farmers can access or acquire land off the incubator, they may have to acquire a new customer base.

Sharing Resources

- Incubator farming requires navigating interpersonal politics, sharing equipment and land, and investing time in relationships and communication with other farmers.

Investing In a Temporary Situation

- Incubator programs are generally meant to be short term, so farmers may be investing in improving fertility on land that they must eventually leave and in local markets that they may not be able to access once leaving the incubator.

Examples of Farm Incubators

- The Intervale Center, Burlington, VT: provides discounted leases, mentorship program, shared equipment, greenhouses, irrigation, storage, food hub, community exposure.

- New Entry Sustainable Farming Project, Lowell, MA: provides plowing, field scale fertility and pH applications, irrigation, fall cover crop seed, field training, greenhouses, storage sheds, shared equipment, produce wash stations, and business and production plan support.

- Urban Edge Farm, Providence, RI: provides access to land, educational programs, access to markets, equipment, and training in organic farming practices.

- Minnesota Food Association/Big River Farms, Marine on St. Croix, MN: provides primarily immigrant and minority farmers with instruction and certification for organic vegetable production, access to resources and markets for growing, selling, and distributing those vegetables, a forum to develop and practice business skills, and access to demonstration/production plots for growing vegetables.

To learn more about farm incubators, see the Farm Incubator Toolkit developed by the National Incubator Farm Training Initiative.

Leasing

A collaborative farming arrangement can also take the form of a lease. Although farm leases can be straightforward transactions with a landlord renting land to a tenant in exchange for cash or other value, leases offer extreme flexibility in creating a more collaborative landlord-tenant relationship. Landlords can offer knowledge, skills, and equipment in addition to land, and tenants can offer their own complementary knowledge, skills, and labor to create a collaborative farming relationship that provides value to both parties.

There are an infinite number of ways landlords and tenants can work together to add value for each other. As one example, in addition to farming cooperatively, Our Harvest, a worker-owned fruit and vegetable farm, leases land from a cattle farmer. As part of the lease agreement, the landlord grazes his cattle on portions of the farm that are not suitable for vegetable growing. This allows both parties to utilize the property while making access to land more affordable for the farmer tenants.

The leasing section of this toolkit offers an in-depth look at farm leases, and the innovative models section of the toolkit provides information about land access via innovative leasing models. Farmer stories within this toolkit that address collaboration through leasing include Say Hay Farms, Sunbow Farm and Growing Veterans.

Formal Business Entity

Choosing a farm business model that allows for collaboration is another way farmers can work together. However, farmers should understand that incorporating as a legal entity (especially when multiple people are involved) requires time, effort, and money. Entering into a formal business arrangement also involves undertaking serious legal and financial obligations. It can be difficult and expensive to extricate yourself from ownership in a business entity, especially a closely-held, small business with only a few collaborators. Accordingly, it’s best to consult with an experienced attorney before agreeing to formally participate in a legal entity with other farmer-owners.

The following sections discuss three types of legal business entities that could be used for farmer collaboration: 1) Legal Cooperative; 2) LLC; and 3) Formal Business Partnership. Other types of formal business entities are also available to farmers, depending on your state. In some states, though, corporate farm laws restrict or prohibit business entities from owning farmland except in certain circumstances (like family ownership of the business entity). Check your state’s laws and/or consult with your state department of agriculture and an attorney before transferring ownership of farmland to a new business entity.

For additional reading on farm business entity selection, see the Farm Commons guide “Farmer’s Guide to Choosing a Business Entity.”

Legal Cooperative

A legal cooperative is a legal entity formed under state law that is owned and controlled by its members. Farms can benefit from the cooperative model because it allows producers to share processing and distribution costs.1 Agricultural cooperatives are also allowed, via the federal 1920s-era Capper-Volstead Act, to set prices together as a large group, which would otherwise likely violate federal antitrust price-fixing laws.2 As a result of the Capper-Volstead Act, farmer/producer cooperatives have historically been placed on a more equal footing with large corporate agribusiness and have consequently played a major role in American agriculture. Familiar household brands such as Organic Valley, Cabot Creamery, Ocean Spray, Land O’Lakes, and Blue Diamond Growers are all large producer cooperatives owned by their member-producers. In fact, 30 percent of all agricultural production in the United States is marketed by a relatively small number of producer cooperatives.3

While large producer cooperatives are common in the agricultural sector, the “members” of these cooperatives are generally individual farmers or individual farm businesses. It is less common for an individual farm itself to be set up as a cooperative, but interest in new approaches to farming collaboratively is increasing and some individual farms are attempting the cooperative model.4 For example, Our Harvest is a worker-owned cooperative established in 2012 that grows and markets produce in Cincinnati. For most farms that set themselves up as cooperatives, the “members” of the farm are individuals who have invested in the cooperative.

Pros And Cons of Legal Cooperatives

Pros And Cons of Legal Cooperatives

Advantages

Advantages

One benefit of organizing as a legal cooperative is the ability for farmers to share the costs and risks of, for example, investing in farmland, marketing agricultural products, packing and/or processing agricultural products, creating and marketing value-added agricultural products, and transporting and delivering agricultural products. The shared ownership and democratic control of a cooperative may be particularly conducive to a successful collaborative enterprise. Additionally, cooperatives are often explicitly values-based (unlike most business entities) and can provide a formalized way for farmer-members to participate in an enterprise with shared values.

Forming a cooperative may also allow a group of farmers to access a piece of property or a warehousing/packing/processing facility that would be too expensive or too large for them to afford or to make use of individually.

However, to realize the potential of any of these benefits, all potential members of the cooperative must consider: 1) their individual business needs and goals; 2) the financial cost of administering the cooperative and shared enterprises; and 3) the time and effort involved in running the cooperative. Especially if the members of the cooperative will have separate agricultural enterprises, each member must consider the potential for growth and development of each individual business endeavor and whether their business can support the additional overhead that may be required to run a shared cooperative enterprise (like rent, labor, professional fees, property taxes, equipment, etc.). Thoughtful up-front planning and continuing communication between members is essential to ensure that each member’s needs can be met by creating a new entity using the cooperative model.5

Note that joining an existing producer cooperative is much different from creating a new cooperative from scratch. Farmers joining an existing cooperative would likely have far less control over the cooperative entity (and would have to agree to follow the cooperative’s existing rules) but would also likely end up shouldering far less of the cost and risk of running the cooperative entity.

Disadvantages

Disadvantages

Many states have detailed requirements that must be met before you can legally call your business a cooperative.6 Choosing to form a cooperative may involve more attention to statutory requirements (meaning, more time spent on the formation process and more money spent on lawyers) than choosing to form other business entities (like LLCs).

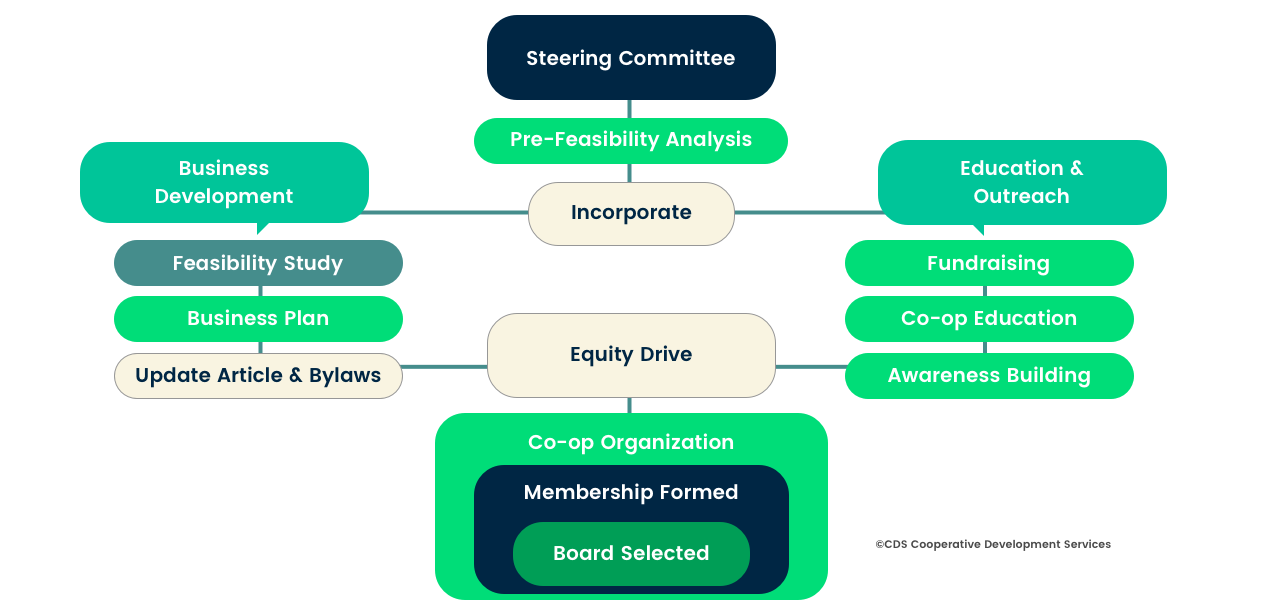

Additionally, best business practices for cooperative formation can include: 1) formation of a cooperative steering committee; 2) a pre-feasibility analysis; 3) legal incorporation of the entity and formation of a board; 4) business development work (feasibility study, business planning, updating articles and bylaws); 5) education and outreach (fundraising, cooperative education, awareness building among potential members and customers); 6) an “equity drive” to raise capital from members to fund the business; and 7) on-going cooperative management and marketing. All of these steps require money and time, and some require professional services fees (like consultant or attorney fees). For more information about cooperative development best practices, see the Cooperative Development Services “Co-op 101” presentation.

Thus, from a business perspective, the legal formation, business setup, and management of a cooperative may cost more in time and money than the profits farmers can earn using a cooperative business model – especially if the planned cooperative will have a relatively small number of members funding and participating in the endeavor. For a small group planning to farm collaboratively, forming and managing an LLC (see below) may be a more flexible and less expensive approach to achieving the same goals as a cooperative. Also, for a small group that wants to farm collaboratively, working through the details necessary to form and manage any type of business entity (whether a cooperative, LLC, or other entity) should prompt important conversations about expectations and goals that can prepare the group for success.

The management of a cooperative may cost more in time and money than the profits farmers can earn using a cooperative business model – especially if the planned cooperative will have a relatively small number of members.

Accordingly, unless the prospective cooperative members have the financial and time resources necessary to effectively form and manage a legal cooperative, farming as a legal cooperative is not necessarily the best way to arrange a collaborative farming situation. However, if the farmers involved have the administrative capacity to form and manage a cooperative, the ability to access consultants and lawyers with expertise in this area, and have enough product flowing through the business to make the arrangement financially worthwhile, the benefits can outweigh the costs.

Owning Farmland as a Cooperative

One important initial consideration for cooperatives planning to invest in farmland is whether and under what circumstances your state allows cooperatives to own farmland. Many states have placed restrictions on the types of business entities that can engage in farming or that can own agricultural land.7 This means that some business entities may not be legally allowed to own farmland in certain states. However, of the states that have these “corporate farming laws,” some explicitly exempt cooperative associations from the restrictions if certain conditions are satisfied. Other states, though, exempt nonprofit corporations from their corporate farming laws but do not exempt cooperatives.8 Because your state’s unique laws will determine whether owning farmland cooperatively is an option, it is important to consult an attorney in your state if you are considering forming a cooperative to own farmland. A different type of ownership arrangement may make more sense for farmers in states that tightly restrict cooperative farm ownership.

Bottom Line on Cooperatives

The bottom line is that forming a cooperative can be complicated, expensive, and time-consuming. Although a cooperative offers valuable features, like cost sharing among members and democratic decision making, farmers will need to commit time and financial resources to conduct up-front and ongoing organizational and legal work to maintain the entity. It will be necessary to find a good lawyer to help, and preferably a lawyer who already has experience working with cooperatives (a specialized area of law). For further reading on collaborative farming via cooperatives, see The Greenhorns’ “Cooperative Farming: Frameworks for Farming Together" and the Cooperative Development Services website.

LLC

For a small group planning to farm collaboratively, forming an LLC (limited liability company) may be a more flexible and less expensive approach that can—if properly set up—achieve the same collaborative goals and incorporate the same values as a legal cooperative.

Farmer Spotlight:

Digger's Mirth

Diggers’ Mirth is a farm composed of five farmer-members who farm cooperatively and share an equal stake in the business. The Diggers’ Mirth farmer-members describe themselves as a “collective” and consider their method of farming to be truly collaborative. Formally, though, Diggers’ Mirth is an LLC. The farm’s operating agreement describes how the farmers share responsibilities, profits, and ownership while simultaneously reflecting and encouraging the members’ collaborative spirit. The operating agreement also lays out issues such as how the members get paid, the payout system upon exit from the LLC, and the procedure for a person to join the LLC as a member.

Prior to 2007, the Diggers’ Mirth farming business was a general partnership by default. Realizing the risks inherent in this general partnership arrangement (see more below), the Diggers decided to formalize the business to protect the members from unnecessary liability. They chose to form an LLC because it was the most similar to their previous collaborative arrangement in terms of filing taxes and business structure. “We wanted to be a cooperative but we didn’t want to deal with the differences in filing taxes and creating a board. We liked how we were but we didn’t want to be personally liable," one farmer-member explains.9 Each of the five Diggers is an equal member of the LLC with respect to decision making. That means even if each member works a different number of hours, their decision-making power is equal.

Thoughts on collaborative farming and LLCs from Hilary Martin, Diggers’ Mirth farmer and LLC member:

“Some people would find it difficult to share in decision making. For me, it’s how I prefer to work. We are all motivated by each other. We are happier showing up and knowing that the business incorporates five minds and not just one. It feels healthier in terms of personal health."

Transferring a farm through an LLC is another method of LLC-based collaborative farming. In the transfer of Eric and Alison Rector’s Windswept Farmstead Cooperative, for example, the senior farmers are slowly passing their farm down to the incoming farmers via an LLC that the senior and junior farmers own collectively (at different percentage ownership levels that change as the junior farmers contribute to the farm over time). For more information about LLC-based farm transfers, click here. Additional farmer stories within this toolkit that address LLCs as a collaborative farming method include Wahl Ranch and Sunbow Farm.

Formal Business Partnership

Two or more farmers or farm businesses can also farm collaboratively as a legal partnership. One type of formal business partnership is an LLP (limited-liability partnership), which is similar to an LLC. For general legal information on LLP formation and management, see the NOLO partnership resource list.

One major pitfall to avoid when farming collaboratively is inadvertently becoming part of a default general partnership. If you share profits and losses or if you refer to any co-collaborator as a “partner,” you run the risk of becoming a general partnership by default. General partners are liable for all of the acts and debts of the other partners, which is a very risky situation. If you plan to act as true business partners, it is best to set up a formal arrangement either as an LLC, a limited liability partnership, a corporation, or another formal business entity that limits farmer-member liability and therefore does not carry the risks of a default general partnership.

For more information regarding additional types of business entities and farm business entity selection, see the Farm Commons guide “Farmer’s Guide to Choosing a Business Entity.”

How An Attorney Can Help

How An Attorney Can Help

The Attorney’s Role

It’s not an attorney’s job to make decisions for farmers or to set farm transfer goals. Instead, attorneys can provide information about pros and cons of different options, advice about what is common versus unusual, fair versus unfair, etc. Attorneys can help farmers understand the universe of possible farm transfer goals and help narrow down individual options so that farmers can make final decisions.

How an Attorney Can Help With Collaborative Farming Arrangements

- Help understand the risks and rewards of different types of collaborative farming arrangements, and help you decide which type might best suit your operation.

- Draft a lease that allows for collaboration.

- Properly set up a formal business entity (legal cooperative, LLC, LLP) to be used as a collaborative farming arrangement.

- Draft thoughtful, tailored cooperative bylaws, LLC operating agreement, or partnership agreement that governs how the farm will be managed and how farmers will collaborate.

- Avoid or exit a risky default general partnership situation.

- Make sure that your farm assets are properly “placed into” your LLC.

- Create a fair and reasonable course of action in the event of a collaborator exit.

- Resolve disputes among collaborators or help you protect yourself in a dispute situation.

- Avoid the consequences of commingling personal and business assets.

Related Legal Tools

Additional Resources

Additional Resources

- Land for Good, Accessing Farmland Together: A Decision Tool for Farmers, https://landforgood.org/wp-content/uploads/LFG-Accessing-Farmland-Together-Decision-Tool.pdf.

- Cooperative Farming: Frameworks for Farming Together, A Greenhorns Guidebook, at Chapter 5

- Cooperative Development Services, CDS Co-op 101 Presentation

- Farm Commons, Farmer’s Guide To Choosing A Business Entity

Footnotes

1. Types of Cooperatives, Northwest Cooperative Development Center, page 1, available at http://nwcdc.coop/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/CSS01-Types-of-Coops.pdf.

2. Donald M. Barnes and Christopher E. Ondeck, The Capper-Volstead Act: Opportunity Today and Tomorrow, available at https://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=US1999006717.

3. Marjorie Kelly and Shanna Ratner, “Keeping Wealth Local: Shared Ownership and Wealth Control For Rural Communities: A report for the Wealth Creation in Rural America project of the Ford Foundation,” available at: http://community-wealth.org/sites/clone.community-wealth.org/files/downloads/report-kelly-ratner09.pdf.

4. See generally Faith Gilbert, Kathy Ruhf, and Lynda Brushett, Cooperative Farming: Frameworks for Farming Together, A Greenhorns Guidebook, available at https://greenhorns.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Greenhorns_Cooperative_Farming_Guidebook.pdf.

5. See Faith Gilbert, Kathy Ruhf, and Lynda Brushett, Cooperative Farming: Frameworks for Farming Together, A Greenhorns Guidebook, at Chapter 5, available at https://greenhorns.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Greenhorns_Cooperative_Farming_Guidebook.pdf.

6. For example, Vermont law prohibits use of the word “cooperative” in relation to a business entity unless certain specific requirements are met. See 11 V.S.A. § 981, available at https://legislature.vermont.gov/statutes/section/11/007/00981.

7. See National Agricultural Law Center, Corporate Farming Laws, available at http://nationalaglawcenter.org/research-by-topic/corporate-farming-laws/.

8. For example, Nebraska; see Pig Pro Nonstock Co-op. v. Moore, 253 Neb. 72, 568 N.W.2d 217 (1997), available at https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/1308304/pig-pro-nonstock-co-op-v-moore/?.

9. Note that an LLC, even if properly maintained, cannot protect individual LLC members from all personal liability.

The Center for Agriculture and Food Systems is an initiative of Vermont Law School, and this toolkit provides general legal information for educational purposes only. It is not meant to substitute, and should not be relied upon, for legal advice. Each farmer’s circumstances are unique, state laws vary, and the information contained herein is specific to the time of publication. Accordingly, for legal advice, please consult an attorney licensed in your state.