Community Supported Agriculture

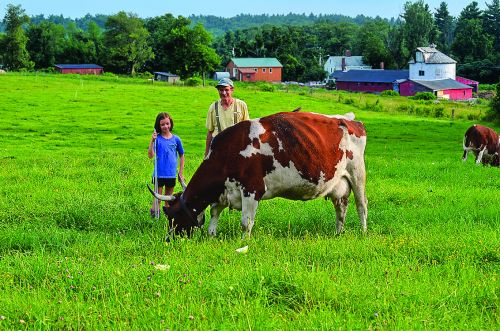

The Temple-Wilton Community Farm has been operating a year-round CSA (community supported agriculture) program since 1986, making it the oldest continually-running CSA in the country. The 200-acre farm supplies 110 CSA member families with over 40 different kinds of vegetables and herbs, milk, cheese, yogurt, eggs, beef, veal, pork, and chicken. Temple-Wilton is located in and around the Abbott Hill area, where historically a farm called Four Corners Farm was located. The aptly named Temple-Wilton Community Farm straddles the border between the New Hampshire towns of Wilton and Temple. Temple-Wilton operates according to biodynamic principles and employs a multi-species grazing system. This means they rotate sheep, cattle, and chickens across the pastures – a system that promotes the health of the animals, the land, and the people.

Many CSAs operate by selling a share of the harvest in exchange for a fixed amount. In contrast, Temple-Wilton first drafts an operating budget for the farm each year and then divides that figure by the number of adults who have pledged to participate in the CSA. This yields an average amount per household. CSA members are encouraged to consider the farm’s needs and their own needs when determining what amount of money to contribute. Each year, some CSA members who can afford to pay more for their shares actually do pay more, thereby enabling others who cannot pay the average amount to pay less and still partake in the harvest. The harvest share includes vegetables for a full year and up to 3 gallons of milk each week. Produce is available at the farm two days each week for pickup and families are encouraged to take an amount that they think they will use; shares are not fixed unless supply is limited.

The farm sells its surplus milk to the public or uses it to make yogurt and cheese, and sells meats, breads, cookies, maple syrup, and herbal teas at the farm’s store. All goods are sold at a small profit to help with costs that are not covered by CSA-member pledges. Extra produce is sold to the Hilltop Café, which is located nearby and is committed to using fresh, local, and organic ingredients to create nourishing meals. The Café’s vision of “nourishing” the community complements Temple-Wilton’s ethic.

The Roster

The story of Temple-Wilton is as wonderful as it is complicated. It may be helpful to refer to the following roster to keep track of the various entities.

The story of Temple-Wilton is as wonderful as it is complicated. It may be helpful to refer to the following roster to keep track of the various entities.

- Temple-Wilton Community Farm – shorthand: the farmers. Temple-Wilton Community Farm was originally an unincorporated (not legally formed) association of farmers.

- Four Corners Cooperative, Inc. – shorthand: current Temple-Wilton Community Farm. The co-op is composed of the farmers and CSA members of the Temple-Wilton Community Farm. It is newly formed and has mostly taken the place of the previous unincorporated association.

- The Educational Community Farm – shorthand: the nonprofit. The Educational Community Farm is a New Hampshire non-profit corporation formed to support the Temple-Wilton Community Farm. The Educational Community Farm does many of the fundraising and land deal-making activities associated with Temple-Wilton Community Farm.

- Yggdrasil Land Trust – shorthand: the current landlord. Yggdrasil Land Trust owns many parcels that make up the Temple-Wilton Community Farm. Yggdrasil has given a lease to the Education Community Farm for the benefit of the Temple-Wilton Community Farm.

- Four Corners Farm – the name of the farm that had operated historically in the area that is now the Temple-Wilton Community Farm. The then-Four Corners Farm and the now-Temple-Wilton Community Farm are located in the Abbott Hill area that straddles the towns of Temple and Wilton.

- Senator Development LLC – shorthand: the former landlord. Previously, Senator Development owned the land that had historically been Four Corners Farm. During its ownership, a conservation easement was put on some of the land, and Senator Development entered into a lease with Temple-Wilton. Eventually, Senator Development sold its holdings to Temple-Wilton.

How It All Began: A Common Vision

In 1985, the three founding Temple-Wilton farmers began discussing the idea that eventually, combined with the work of other farms and farmers, became what is now known as Community Supported Agriculture (CSA). Trauger Groh, Lincoln Geiger, and Anthony Graham wanted to collaboratively provide wholesome food for their local community while maintaining good stewardship of the land. Anthony has been growing vegetables at Temple-Wilton since the farm began in 1986. Lincoln has been the dairy farmer for over 30 years, milking the cows, managing the hay, and repairing the equipment. Trauger grew vegetables and maintained a small herd of cows and then retired from active farming a few years ago. He passed away in 2016.

It all started with several preliminary discussions, after which Trauger drafted an “Aims and Intentions” document detailing the farmers’ agreement. The agreement explains the spiritual, legal, and economic aims of the group. Notably, one of the aims is “to make access to farmland available for as many people as possible through the use of covenants and easements that protect the land from development in perpetuity.”

Temple-Wilton defines itself as “a free association of individuals, which aims to provide life-giving food for the local community and to respect the natural environment.” The farmers set forth “principles of cooperation” to govern their collaborative venture, which include how costs will be shared and how budgets will be approved. In addition, the farmers agreed that their overarching motivation would be guided by the agreed-upon “spiritual and nutritional aims, rather than by our financial needs.”

Getting Started With The CSA

In the 1980s, Anthony shared a house with Lincoln, who had training in biodynamic agriculture and had grown up in Sweden. Lincoln moved to a small farm in Temple, New Hampshire, and was interested in acquiring a couple of cows to start a dairy herd. Trauger joined the two after moving to the United States from Germany, where he had engaged in social farming.2

Trauger proposed to Anthony and Lincoln that the three begin a collaborative venture. However, they were looking at a different structure from what became the dominant form of CSA. Rather than ask everyone to contribute a set price and receive a set amount of the harvest, like Indian Line Farm in Massachusetts (the other early CSA that started in 1986), the three chose to present an annual budget and ask prospective members to meet that budget through freely given pledges. That worked for a few years and then it changed to presenting an average amount of money per adult per month based on the projected operating budget. This system gave people a clearer goal. Anthony says about 70 percent of their CSA members pay close to the average amount. The remaining 30 percent includes some people who are able to pay more and some who pay less.

The model was successful. In the first year, the CSA had 35 households and over the next few years, the number of participating families grew to about 100. Today, the farm operates with 110 CSA households and has a substantial waiting list.

Anthony says that all CSAs are unique. Of the several thousand CSAs currently operating in the United States, Anthony comments, “you could go to every one of them and find differences in the way that they operate. They all work differently according to the community of people they’re working with.” Many families who join the Temple-Wilton have children attending the nearby Waldorf schools and the families are committed to living in the area while their children are in school – and usually even after that. Some families have been with the farm for 31 years. “Solid community is a must,” Anthony says. “There is also an interest here in doing things differently – people have an interest in unusual forms.”

Although the farm is successful and thriving now, it has endured its share of tough times. Until the late 1990s, it was not uncommon for the farmers to have a hard time meeting the budget. In April (because the season starts June 1), the farmers would hold a budget and pledge meeting for all the CSA members. Anthony recalls, “sometimes we would have to go round the room two or three times, asking if everyone could add another few dollars per month per adult. . . . We didn’t always meet the budget, but we got along well enough to scrape through.”

Things began to shift after what Anthony terms “a national freakout” in the late 1980s over people who were getting sick from apples treated with the chemical Alar – a substance sprayed on apples to regulate their growth and preserve them in storage. Manufacturers voluntarily withdrew Alar from the market after the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) proposed banning its use due to concerns that it could cause cancer in children. During this period, the organic movement gained ground. From that moment on he said it became easier and easier to meet the budget each year because Temple-Wilton had always farmed biodynamically. “Suddenly, being a member of the farm became much more important for people than it had been. Today people have a real appreciation for what the Temple-Wilton Community Farm is doing.”

Anthony understands that eating biodynamic food can be more expensive but the gains in health and wellbeing are worth the extra cost. This belief informs the CSA practice at Temple-Wilton so that families of varying income levels are still able to participate and partake in healthy, nutritious food.

Unwritten and Otherwise Unstable Leasing Situations

Several parcels of land make up the Temple-Wilton Community Farm, and each was acquired and conserved separately in different ways and at different times.

In the early 1980s, Anthony was working in a small therapeutic community in Temple, New Hampshire, that provided housing and care for disabled people. He began farming on the land that belonged to the therapeutic community.

Meanwhile, Trauger married Alice Bennett – a friend of Lincoln and Anthony who lived two miles down the road in Wilton. Alice had a small 40-acre farm consisting of woods, two ponds and a few fields.

Anthony, Lincoln, and Trauger all began farming on the hodge-podge combination of 1) Lincoln’s leased dairy farm property; 2) the therapeutic community property Anthony had access to; 3) Alice’s property; and 4) some of the hayfields neighboring Alice’s property. Anthony recalls that this system was, “not a great way to go” because they would put a lot of effort into the fields but occasionally the owner would decide to do something different with the land. In addition, the therapeutic community Anthony worked for experienced a turnover in management and the new management no longer wished to allow farming on the property. Achieving stable land tenure was becoming more challenging with every growing season.

Lincoln took his cows to what eventually became Temple-Wilton Community Farm, known historically as Four Corners Farm, on Abbot Hill in Wilton. There, he had leased some land, while at the same time vegetables were grown in West Wilton. Logistically, it was difficult to farm at opposite ends of the town. Eight miles of highway separated the two locations, which posed a challenge to their biodynamic farming methods. Meanwhile, Trauger was growing older and pulling back from active farming.

Anthony moved closer to Four Corners Farm. But, they could not find any land to farm that was suitable for vegetables. During this time period, Lincoln’s lease relationship was growing tense. Anthony recalls, “It was hard to work like that, not having one square foot of land that belonged to us.”

Initial Solution: Creating the Nonprofit Educational Community Farm

In the late 1990s, Temple-Wilton could have simply been described as a group of people growing their food together. It was difficult to negotiate with landowners and it was difficult to own anything, so the Temple-Wilton farmers, together with a few CSA members, formed a New Hampshire nonprofit called the Educational Community Farm. The board members of this newly formed nonprofit included farmers and CSA members. The creation of this entity later proved important in helping to purchase and lease land and to finance and hold equipment for Temple-Wilton’s use.

Securing Land

By the early 2000s, the Temple-Wilton dairy was operating at Four Corners Farm on Abbot Hill in Wilton under a rather tenuous short-term sublease agreement. The Educational Community Farm nonprofit would have liked to purchase the farm at that time. But, the Educational Community Farm didn’t have the money and the Temple-Wilton farmers were not interested in allowing time for fundraising.

It was becoming clear that Temple-Wilton needed to secure its land base or the farm might not survive.

Orchard Owned by Land Trust, Land Trust Leases to Farm

In the spring of 2001, four Temple-Wilton families purchased an old orchard of approximately 40 acres. This group formed an LLC together to own the property. They had a plan that once enough money was raised to pay back the LLC, they would resell the property. They accomplished this largely through a New Hampshire Land & Community Heritage Investment Program (LCHIP) grant. They resold the property to the Yggdrasil Land Foundation. Yggdrasil is a land trust with the stated purpose of supporting biodynamic, sustainable, and organic practices to ensure that healthy land remains available for future generations to farm. Yggdrasil achieves its mission by securing land in perpetuity for current and future generations of farmers, either by purchasing parcels or receiving gifts. Integral to putting Yggdrasil in a position of owning this 40-acre area was a lease back to Temple-Wilton so that the farming was not interrupted and could continue for the long-term. See more about this lease below.

In the spring of 2001, four Temple-Wilton families purchased an old orchard of approximately 40 acres. This group formed an LLC together to own the property. They had a plan that once enough money was raised to pay back the LLC, they would resell the property. They accomplished this largely through a New Hampshire Land & Community Heritage Investment Program (LCHIP) grant. They resold the property to the Yggdrasil Land Foundation. Yggdrasil is a land trust with the stated purpose of supporting biodynamic, sustainable, and organic practices to ensure that healthy land remains available for future generations to farm. Yggdrasil achieves its mission by securing land in perpetuity for current and future generations of farmers, either by purchasing parcels or receiving gifts. Integral to putting Yggdrasil in a position of owning this 40-acre area was a lease back to Temple-Wilton so that the farming was not interrupted and could continue for the long-term. See more about this lease below.

Four Corners Farm: Initial Lease, Then Purchase With Better Lease

Meanwhile, part of Temple-Wilton continued to operate with a lease at the historic Four Corners Farm. However, the land making up historic Four Corners Farm was sold to a development company, Senator Development LLC, in the 2003 and 2004 timeframe. This created the risk that the land would be commercially developed or otherwise no longer available to Temple-Wilton.

The nonprofit formed to support Temple-Wilton, the Educational Community Farm, negotiated with Senator Development. Based on a plan with Senator Development, the Educational Community Farm began fundraising to establish a conservation easement on 68 of the original 140 acres of the Four Corners Farm, and a 99-year lease to Temple-Wilton. A year later, by the spring of 2004, the Educational Community Farm had raised enough money. As a result, a conservation easement was put on the land of the historic Four Corners Farm, protecting it forever against commercial development. The easement is now held by the Wilton Conservation Commission. Significant financial help came from another Land & Community Heritage Investment Program (LCHIP) grant and other sources of funding such as the USDA’s Farm and Ranch Lands Protection Program, the town of Wilton and many farm members and friends. The original farmhouse, which consisted of two apartments (one of which later became the Hilltop Café), were rented separately by the owner.

Senator Development also executed a 99-year lease with the Educational Community Farm for $1 per year. Anthony recalls that the long-term lease and relationship with the developer provided some stability, but it was not without certain drawbacks: “It could be done but it wasn’t great because it wasn’t ours. And it also wasn’t great because every improvement we made would eventually go to the owner.” The lease provided that any improvements made to the barn, and new buildings or structures such as apprentice housing, all accrued to the landlord.

As time went on, the farmers became concerned about having such a large portion of the farm still owned by a private, for-profit entity, Senator Development LLC. The farmer especially wanted the land to remain available and in agricultural use for future generations of farmers. Thus, they began working with community organizations and with Yggdrasil to explore the feasibility of raising enough funds to purchase Four Corners from Senator Development. They explored every avenue, and it took a long time.

Eventually, they cobbled together the necessary $576,000, as follows:

- 340 donations

- 2 grants from New Hampshire Charitable Foundation, New Hampshire’s statewide community foundation, which manages a growing collection of more than 1,800 funds, and awards nearly $40 million in grants and scholarships every year

- 24 individual loans

- A loan from the New Hampshire Community Loan Fund, which serves as a catalyst, leveraging financial, human, and civic resources to enable traditionally underserved people to participate more fully in New Hampshire’s economy. The New Hampshire Community Loan Fund aggregated and manages all of the individual loans.

After purchasing the historic Four Corners Farm, where the Temple-Wilton Farm had now been operating for decades, the Community Farm leased the farm to the newly-formed Four Corners Cooperative, Inc., as discussed below.

Other Purchases & Leases

At various times several other pieces of land also on Abbot Hill came up for sale. The supporting nonprofit, the Educational Community Farm, worked with the Temple-Wilton farmers, CSA members, and others. Together, they used a variety of different mechanisms to secure more of a land base for Temple-Wilton. One parcel was financed by a generous CSA member. Other parcels were purchased by the farmers themselves.

Anthony and his wife Glynn were able to purchase three parcels (18 acres in total) with some financial assistance from their family members and some financing. Once they owned the properties, Anthony and Glynn sold a conservation easement on the land. The Town of Wilton, the State of New Hampshire, and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) through the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) pooled funds to purchase the conservation easement. The proceeds from the conservation easements helped pay off the mortgage loans. The underlying ownership in the land (the fee interest) was then donated to Yggdrasil Land Foundation. As it had before, an integral part of this deal was that Yggdrasil provided a 99-year lease to the Educational Community Farm. This helped Temple-Wilton further its security in the land it was farming.

Similarly, Lincoln was able to purchase an 18-acre parcel of land. He, too, sold a conservation easement on the property to Yggdrasil (again funded by the Town of Wilton, the State of New Hampshire, and the Natural Resources Conservation Service). Lincoln also used the proceeds from the conservation easement to pay off the mortgage on the land. Just as Anthony had done, Lincoln donated the conserved land to Yggdrasil Land Foundation, and Yggdrasil provided a 99-year lease to the Educational Community Farm for the benefit of Temple-Wilton.

The Rolling, 99-Year Ground Lease

As described above, Yggdrasil Land Foundation now owns several portions of Temple-Wilton and has given a lease to the Educational Community Farm for the benefit of Temple-Wilton. Yggdrasil and the Educational Community Farm have one written lease that covers all the different parcels that Yggdrasil owns. The lease is written to also cover any future parcels that Yggdrasil may come to own which are also part of Temple-Wilton.

The lease is a ground lease, meaning that the buildings and structures are not leased (the Educational Community Farm owns them) – only the underlying land is leased:

This lease and the terms included in it cover the use of the purchased and gifted lands, but excludes improvements to existing structures and any new farm or residential buildings that may be constructed on the current and future properties.

The lease does not prohibit building new structures or improving existing ones. But, given that Yggdrasil owns the land, it makes sense for Yggdrasil to be in the loop with any construction activities. So, the lease gives Yggdrasil the right to review and approve any building plans. To make sure that Yggdrasil uses that power in a balanced and fair way, the lease provides that Yggdrasil cannot “unreasonably withhold approval.”

The lease term runs for a period of 99 years, commencing on January 1, 2004. Given the long duration of the lease term, the parties agreed that they will review the lease together at regular 5-year intervals to reassess whether the lease continues to meet the needs of both parties.

Because Yggdrasil’s charitable mission is to support the type of farming that Temple-Wilton does, the lease does not call for payment of fair market rent. Instead, the lease calls for a combination of payments designed to cover Yggdrasil’s costs. First, the lease required a one-time, upfront contribution from the Educational Community Farm to Yggdrasil in the amount of $5,000 (which was paid in 2004, when the lease was set up). Second, the lease provides that the Educational Community Farm bears all annual costs relating to the leased property (including taxes, maintenance, and operating charges). Third, the Educational Community Farm pays a nominal rent of $1 per year for the remainder of the 99-year lease term. Fourth, the Educational Community Farm must pay an amount to Yggdrasil each year to cover Yggdrasil’s “stewardship” costs. Stewardship means the efforts Yggdrasil must make to ensure that its lands are being used appropriately. This typically includes annual inspections and communications, and sometimes, reports from consultants. The Educational Community Farm’s stewardship contribution is set at 1% of the CSA’s operating budget.

The lease term is rolling, meaning it automatically renews itself at its expiration, as indicated by the following language, “Ninety-nine (99) years, with automatic extensions of additional ninety-nine year terms.”

The lease prohibits the Educational Community Farm from using any hazardous materials on the land, which are defined to include synthetic pesticides. The lease is also assignable, meaning the Educational Community Farm can give its rights under the lease to another entity, provided that the Educational Community Farm obtains prior approval to do so from Yggdrasil. The lease further states that the Educational Community Farm is responsible for all maintenance and repairs. Any buildings, structures, or other improvements left on the land at the expiration of the lease term become the property of Yggdrasil. The parties clearly spell out the procedure to be followed in the event of a default by either party and designate New Hampshire’s laws as the laws applicable to any disputes.

Raising Money For Conservation Easements

As is frequently the case, many helping hands came together to secure the money needed to put conservation easements on much of the land now comprising Temple-Wilton Community Farm.

As is frequently the case, many helping hands came together to secure the money needed to put conservation easements on much of the land now comprising Temple-Wilton Community Farm.

The Farm and Ranch Lands Protection Program (FRPP) provided $125,000 towards the purchase price. The FRPP is currently known as the Agricultural Conservation Easement Program (ACEP). ACEP is a federal program through USDA that provides financial assistance to farmers who wish to conserve their land and help ensure that agricultural land remains in farming, thereby providing important protection to the nation’s food supply.

The State of New Hampshire, acting through the Land & Community Heritage Investment Program (LCHIP), also has an executory interest pursuant to New Hampshire state law RSA 227-M. An executory property interest is a future interest in a property right that will not be triggered unless a specified event occurs. Here, should the Town of Wilton at some point in the future be unable to retain and enforce the conservation easement, the State of New Hampshire would then own the conservation easement. Conveying an executory interest in the conservation easement to the State of New Hampshire was required under LCHIP (see LCHIP Criteria, Guidelines, and Procedures). In the event that the Executory Interest Holder could not enforce the terms of the easement, then the United States of America would have the right to enforce the easement. Thus, both the State of New Hampshire and the United States of America have reasonable access to the property to inspect and ensure compliance with the easement.

The Cooperative

Temple-Wilton Community Farm has always operated as a collaborative association of individuals. In the spring of 2016, the farmers and members of the CSA formed a member-owned cooperative called the Four Corners Cooperative, Inc. The co-op does business under the name of the Temple-Wilton Community Farm. The stated purpose of the co-op is as follows:

The Farm is dedicated to providing biodynamically grown food for the local community while building and maintaining the fertility and life diversity necessary for a self-sustaining farm organism on the lands entrusted to it. The Farm shall retain all net surplus for re-investment in the stewardship and further development of the farm organism. Individual profit from farming is not an economic aim of the Farm. Our guiding principles in this effort derive from the Aims and Intentions originally set forth by our founding farmers.

Membership in the co-op is open to farmers and CSA members at Temple-Wilton, “the only restriction being the amount of food [the farm] can produce.” The voting structure is based on a one vote per member model. The co-op has bylaws and the bylaws detail the voting procedures and the format for holding member meetings, and set forth the responsibilities of the Board of Directors. The bylaws also provide a procedure to follow to amend the bylaws, and what to do in case the co-op comes to an end or dissolves.

The Current Results

At the end of the day, Temple-Wilton has secured stable and equitable land tenure for current and future generations of farmers as follows:

- Yggdrasil owns the “orchard” (now converted to a hayfield), which is protected by permanent deed language associated with New Hampshire’s Land & Community Heritage Investment Program (LCHIP). Yggdrasil leases the orchard land to the Educational Community Farm via the 99-year rolling ground lease.

- Yggdrasil owns three vegetable fields and one hay field. The Town of Wilton holds a conservation easement on all of this land. The Educational Community Farm leases this land from Yggdrasil under the 99-year rolling ground lease.

- The Educational Community Farm owns what had historically been known as Four Corners Farm, which is protected by a historic preservation and conservation easement with the Town of Wilton and LCHIP.

- All farmland and agricultural buildings held by the Educational Community Farm, either by outright ownership (as in the historic Four Corners Farm) or by lease (as with those lands owned by Yggdrasil) are leased to the newly formed Four Corners Cooperative, Inc.

Plans For Farm Succession

The farmers do not own the farmland or much equipment. Rather, the Educational Community Farm and the co-op own most of the equipment. So, a succession plan for the CSA is not necessary in the traditional sense. However, while succession is not required in terms of goods and property, it is required with regard to the farmers. The founding farmers need to feel that new farmers will carry on with Temple-Wilton’s original aims and intentions.

As of 2016, a second vegetable farmer, Jacob Holubeck, has joined Anthony and will be taking over from him in 2018. On the animal side of the farm, Shelley Lewton and Ben Schlosser have taken over from Lincoln. Also working at the farm is Benjamin Meier, originally from Germany. He joined Temple-Wilton several years ago and is the cheese maker. The farm currently takes in five apprentices each year and is listed as an official “Mentor Farm” with the registry maintained by the Biodynamic Association (USA) apprenticeship program.

Lincoln has become involved with an organization called the Gaia Education Outreach Institute (the GEO Institute). Its mission is to educate children and adults through experiential learning in all aspects of agriculture, forestry, and horticulture, among other outdoor endeavors. The GEO Institute is located next to Four Corners Farm. The GEO board and Lincoln have engaged in fundraising efforts to secure that piece of land for the Wild Rose Educational Farm. Lincoln hopes that his work with the GEO Institute will help to fund his retirement.

The co-op is working on setting up a more formal retirement fund for the new farmers.

Advice For Collaborative Farmers Of The Future

When reflecting on his own experience of collaborative farming and reaching stable land tenure, Anthony tells others who might embark on a similar path:

“If you’re just starting out, it’s hard to know what you have to do and how you have to do it, but one of the things that is crucial is to try to gain access to land that is protected into the future for the purpose of farming. If that is not possible you could well be wasting your time.”

In terms of achieving stable land tenure, Anthony does not believe that the solution involves gaining ownership of land in the traditional sense. He believes it is better for the earth and the community if the land can be protected and held by a land trust so that there is no chance of the land eventually becoming someone’s nest egg and being sold for development. The farmers and food producers of the future need stable access to land, and in his view that can best be achieved with a community farming model and the use of conservation easements and land trust organizations.