“To do this kind of arrangement, everyone has to be willing to give up something to get something.”

– Eric Rector

The Backstory

In 1990, Eric and Alison Rector moved to a 100-acre piece of farmland in Monroe, Maine. Since that time, they have used the land as homesteaders to grow much of their own food, while engaging in a variety of other enterprises. Eric has always worked full time with computer systems, but became an IT consultant in 2003 and primarily works from home, telecommuting. He also continues to run an artisanal cheese and yogurt business from the farm, selling at the Belfast Farmers Market and some local retailers. His wife, Alison, ran a bakery business on the farm, but stopped when she began to develop carpal tunnel syndrome. She is also an artist and continues to run a fine arts business with a studio on site. The Rectors occasionally sell apples or cider, but have mostly used the orchards on their property for their personal consumption.

Envisioning A Succession Plan

After Alison turned 50 in 2010, she and Eric began thinking about retirement and devising an exit strategy that would allow them to maintain their lifestyle as homesteaders. They thought about selling their farmhouse, barn, and their 100 acres, but were not ready to sell the entire farm right away. Slowly, the two began developing a 10-year plan. According to Eric, the first year or so was spent brainstorming and musing on what their relationship was to the land and what they wanted it to be in the future. They recognized that they would not be able to simultaneously maximize their profit on their real estate and ensure that the land was maintained in a certain way in accordance with their values and vision. Although the Rectors never farmed the land for a profit, they grew much of their own food using sustainable methods and without the use of synthetic pesticides and fertilizers. They wanted to see the land remain agriculturally and economically viable for future generations.

Eric and Alison came to realize that they wanted to stay on the land in a more limited capacity while backing away from the parts of the farm that were most physically intensive. To that end, they wanted to take on a less active role in maintaining the gardens, orchards, and livestock. They also wanted to build a smaller, more modern house on the hill on their property and vacate the farmhouse. They began wondering if there was an opportunity to allow a younger couple to take on parts of the farm work that they no longer wanted to engage in and, if so, how they could create an equitable arrangement for the new farmers.

Eric recognized that growing a farming business that builds equity is different from, for example, constructing a house that has the potential to immediately begin building equity. Growing a strong farming business requires expending significant time and energy maintaining and/or improving the soil. As Eric puts it, “you are constantly working today for tomorrow and the next day and ten years from now.” Eric did not want to simply lease the land to new farmers; he wanted to transfer the farm in a way that allowed for new farmers to begin building equity – something a typical lease arrangement often doesn’t contemplate. Eric and Alison also wanted to provide an opportunity for new farmers to access land for a farm business without needing a mortgage loan.

At this point, both Eric and Alison realized that if they were envisioning sharing their land with another couple, they would “need to practice.” They recognized that bringing new people into their living space would not be easy, so they decided to move slowly by seeking farm apprentices each year for a period of two years to see if sharing their land was feasible. After successfully having farm apprentices for two years, Eric and Alison felt that they were ready to share their land on a more permanent basis. But where would they find the right farming couple?

Meeting The Right Match

The Rectors posted a listing for their farm on Maine Farmland Trust’s FarmLink matching site. They received 10 different responses to their posting, including one from James Gagne and Noami Brautigam. For each farm couple they met, Eric and Alison hosted a lunch or dinner at the farm, gave a farm tour, and had a discussion about what each person wanted out of any future sort of arrangement. Eric said James and Noami most closely matched what they were looking for. Noami had 10 years of farming experience already (and a business plan), and James enjoyed farming as well, although he worked full-time as a program manager for a veterans housing services organization.

James and Noami were the second couple the Rectors interviewed. They saw the posting on the FarmLink program and were excited by the prospect of the Rectors wanting to transition the property rather than simply selling it and moving. After several discussions, Eric described the situation as the two couples agreeing to “go steady in the summer” of 2014 – meaning that the young couple stopped looking and making offers on other posted properties and the Rectors stopped showing their farm or receiving other offers on it.

James and Noami were the second couple the Rectors interviewed. They saw the posting on the FarmLink program and were excited by the prospect of the Rectors wanting to transition the property rather than simply selling it and moving. After several discussions, Eric described the situation as the two couples agreeing to “go steady in the summer” of 2014 – meaning that the young couple stopped looking and making offers on other posted properties and the Rectors stopped showing their farm or receiving other offers on it.

After a six-month “going steady” period, the couples entered into what Eric called “the fiancé agreement” – a two-year timespan during which the parties sorted out their transition plans. Eric ultimately decided to create a limited liability company (LLC) for the farm as a transition tool that would set forth the terms of the parties’ understanding in an LLC operating agreement and in a separate purchase and sale agreement (PSA). During this two-year period, the LLC essentially operates as a landlord, with Noami and James (doing business as Dickey Hill Farm) paying rent for the farmhouse and access to the land and equipment owned by the LLC (rent is set at the cost of maintaining the assets being rented).

The LLC Agreement

Eric wanted to create an LLC that would own all of the open farmland (including the orchards) and also own all of the infrastructure on the 18-acre property (the farmhouse and barn). Eric notes that there are many different ways to structure such an arrangement; the key idea is that all parties agree to whichever method is ultimately chosen. In Eric’s case, he enlisted an independent appraiser to obtain a static fixed price for the entire LLC-owned property (and thus the price of all the shares to be transferred over time so long as the parties adhere to the scheduled buyout timeline). Eric structured the LLC with a fixed number of units pegged to the appraiser’s valuation, and set up the LLC to be jointly owned by Eric and Alison at the outset. When the PSA was signed, Noami and James owned zero units of the LLC.

At the end of the two-year leasing period, under the PSA, Noami and James become members of the LLC as part owners and begin to buy out all of Eric and Alison’s LLC units. At this point, Noami and James will be writing two checks each month: one to Eric and Alison to buy LLC units (percentage interest in the LLC), and the other to the LLC to pay for leasing LLC-owned assets (farmhouse, barn, field, equipment) that they use.

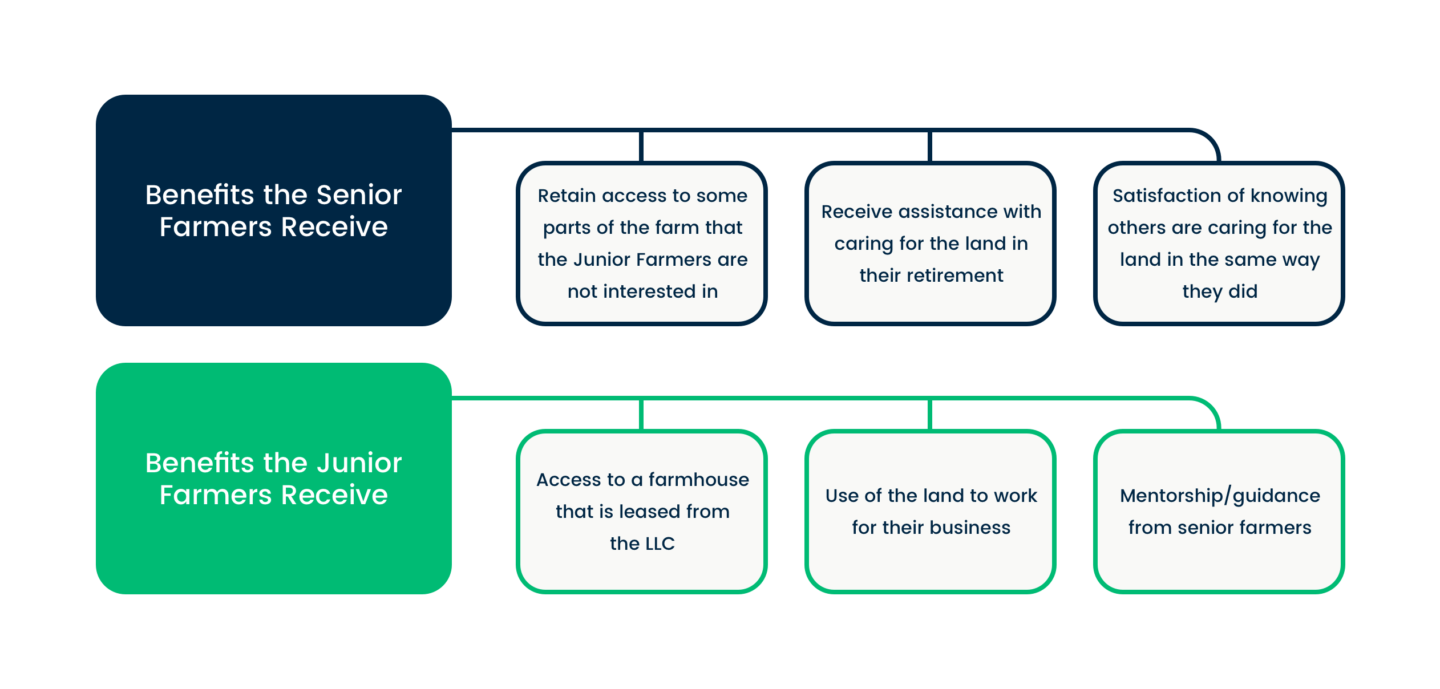

As the junior farmers gain LLC units (ownership) via purchase or other means, the senior farmers lose units and decrease their ownership percentage. Thus, the senior farmers can slowly release their control over the land while still retaining access to the farm (they have since built their new, ultra-modern house on the hill) and receiving help maintaining the property and structures.

During the two-year trial “engagement” period, everyone agreed that either party could back out of the deal (with three months’ notice) and that the money paid into the LLC at that point would simply be considered rent. At the end of the two years, and for additional years thereafter, the money/sweat equity the junior farmers have paid into the LLC then counts toward a purchase of LLC units (and therefore toward the ultimate purchase price of the LLC). Under their PSA, Eric and Alison agreed to sell 100 percent of their units over time, and Noami and James agreed to buy 100 percent of the LLC units. However, a different PSA could specify a limit to the units purchased if that was the mutual desire of the buyers and sellers. A properly set-up PSA and LLC operating agreement can allow for a great deal of flexibility when dictating the means and method of LLC ownership transfer.

The two-year engagement period is set to end in March 2017, and Eric describes the parties’ experience as “so far, so good.” The separate PSA provides that at the end of the two-year leasing period, the next phase of the farm transfer will occur, during which the junior farmers will begin purchasing shares of the LLC over a 20-year period until full ownership is transitioned to the junior farmers. The PSA contains an early buyout provision in case the junior farmers wish to purchase the LLC faster. If at any point James and Noami no longer wish to farm, they can sell the shares they have accumulated back to the Rectors or to new farmers, provided those new farmers agree to abide by the terms of the LLC, which requires – among other things – the use of sustainable farming methods.

Importantly, the Rectors and the junior farmers each used their own attorneys to ensure that the deal was fair and amenable to all parties.

Why an LLC?

Continuing to use parts of the farm was important to the Rectors for several reasons. Regarding Eric’s cheese business, he would still have access to his licensed production facility in the barn during the buy-out period. Most importantly, though, the Rectors had clear ideas about how they wanted their land to be used. It was important to help ensure that the new junior farmers would care for it in ways that were sustainable and ecologically sound. While Eric recognized that he could have placed a conservation easement on the property to prevent the land from being developed in the future, he admitted to being “skeptical about an easement’s ability long term to affect productive fields and their maintenance.” Eric worried that “down the line when a parcel with an easement is transferred to other owners and the original owners are no longer actively involved,” land trusts (or any other nonprofit organization holding the easement) might not be able to keep the fields open for agriculture while maintaining soil fertility. By using an LLC with a detailed, specific operating agreement containing enforceable conditions for using the land that all parties agreed to follow, Eric felt he could alleviate these concerns.

Eric also chose an LLC as a farm succession tool because he wanted to be able to issue units of the LLC and transfer them in a measured way, according to a schedule provided in the operating agreement. This allows the new farmers the option to build equity and to be more likely to see a return on their investment of time, energy, and money than they would in a typical leasing arrangement. From a landowner’s perspective, Eric appreciated that an LLC allowed him to transfer the farm and farm infrastructure bit by bit while retaining a measure of access, control, and oversight for himself and Alison regarding how the land is used. On the other hand, Eric admits that the arrangement is not perfect. He recognizes that he and Alison will not realize the full value of their investment in the land for 20 years, if ever. Eric further recognizes that while an LLC offers the potential for equity for the junior farmers, they are required “to deal with” the senior farmers and the terms provided in the operating agreement. Thus, Eric comments, “to do this kind of arrangement, everyone has to be willing to give up something to get something.” Senior farmers must be willing to give up a fast return on their investment in the land, while junior farmers must be willing to give up a certain amount of control over how they can use the LLC-owned land. However, for senior farmers who wish to transition slowly and junior farmers who lack access to land and a mortgage loan, the arrangement has the potential to accommodate the needs and desires of both parties.

Eric also admits that this type of arrangement could cause the parties to “run into unanticipated stickiness,” which is why “good will and good nature is important.” Eric also cautions that it is “important to be honest about mistakes and how things came up and were settled.” Eric further cautions that this arrangement “isn’t necessarily great for land that is counted on for retirement – but it might be if you start this kind of arrangement 20 years prior to when you want to retire.”

Eric also appreciated the amount of flexibility an LLC allows. The parties could arrange to have the new farmers buy X number of units each month in order to maintain the terms of the PSA. Once the land is appraised and the land price is set, new farmers are able to buy shares at set prices – and the PSA could contain a clause allowing for the land to be revalued every 5 years and LLC unit prices adjusted accordingly. According to Eric, “all kinds of choices can be made” in terms of how and when the transition occurs.

Although not the case here, Eric appreciates that an LLC arrangement could also be used to create opportunities for multiple farmers to use a piece of land and maintain a multi-owner situation. If any of the LLC member-farmers decided they needed to move and sell their assets, they would have LLC units to either sell back to the landowners or to another farmer who could become a new member of the LLC.

For the junior farmers as well, there have been a few lessons learned. First, Noami says that the arrangement has made her and James’ taxes much more complicated. While she’s glad that the couple used their own lawyer while setting up and entering into the LLC, she wishes they had also consulted an accountant to learn about the tax implications of the deal. Additionally, the assets placed into the LLC included not just the land and permanent infrastructure (like the farmhouse and barn mentioned above), but temporary infrastructure as well (like farm machinery and other equipment). While this helped Noami and James start farming right away, Noami says that it “limits flexibility” to upgrade equipment. For example, the couple is not able to trade in a tractor if they’d like to buy a newer version, because they don’t own the tractor outright. Instead, the members of the LLC could vote to sell the tractor, and profits would be distributed as shares. Noami and James appreciate the advantage they had in getting to start farming without the financial capital usually required, but trade-off is some constraints and complications.

An Arrangement Where Everybody Wins

Open Source Agreement

Given Eric’s computer science background and his desire to assist new farmers in their business ventures, Eric wanted to make his arrangement a replicable model for other similarly situated farmers. Thus, he wanted his documents and arrangement to be available in an open source format. You can read more about the Rectors’ and James’ and Noami’s experiences here and see the LLC operating agreement here. Eric agreed to serve as a case study for this toolkit because he would like to see other farmers replicate this legal arrangement and benefit from his experience as they sort out their own farm succession plans.

Epilogue

On March 4, 2017, Eric & Alison and Noami & James signed the initial unit transfer document that welcomed Noami and James to the LLC as equity-owning members who now purchase new units from Eric and Alison on a fixed schedule every month. Things are looking stable and are on track for a long-term commitment. James and Noami were recently married and just added a dog to their farm family. They constructed a large commercial hoop house in the summer of 2016, which provided significant production the following winter. They are building the second of three large hoop houses in 2017 and have invested in an irrigation system that will service all hoop houses, plus an enclosed wash and prep area. For two years, Eric has helped raise, slaughter, and butcher meat chickens for personal consumption, just as he and Alison have done each year. Eric also continues to produce award-winning cheeses and yogurt in the production facility he built into the barn, as well as press cider from the mature apple trees on the property. Little by little, the farmstead cooperative is an idea coming into fruition.