LLC-Based Farm Transfer

Overview

Overview

LLCs (limited liability companies) can be used to transfer farmland and farm businesses to one or more people over a period of time. LLCs are extremely flexible entities that allow transitioning (senior) farmers to maintain a level of control of their farm operation while simultaneously conducting a gradual transfer of farm ownership to new (junior) farmers. LLCs also allow flexibility for incoming farmers in terms of the amount and type of financing required to transition into farm ownership. Additionally, LLCs can facilitate transfer of some farm ownership rights to non-farming heirs (children not interested in farming) while still allowing control, ownership, and access for farming heirs (children interested in farming) or other new farmers.

However, farmers should note that using an LLC to transfer a farm operation will almost always require a lawyer’s help to make sure the transfer actually happens according to farmers’ wishes. For example, farmers will need a lawyer to draft an effective LLC operating agreement, which is a contract between the LLC members. A clear, legally-effective operating agreement is critical because it will govern ownership of the farm over time. A good operating agreement should also provide an exit path for farmer members that maintains the value and undivided nature of the farm operation in case the LLC-based farm transfer deal falls apart.

The bottom line is that although using an LLC to transfer a farm operation can provide the benefit of a highly-individualized and gradual transition of farm ownership, a successful LLC-based farm transfer must also conform to strict legal rules, requires farmers to create formal legal agreements and complete legal paperwork, and may also demand compliance with certain state laws.

Thus, an LLC-based farm transfer should not be attempted without the help of an experienced attorney.

Farmer Spotlight:

Windswept Farmstead Cooperative LLC and Dickey Hill Farm

Monroe, Maine farmers Eric and Alison Rector created an LLC (Windswept Farmstead Cooperative LLC) to help them transition their diversified organic farm operation to a pair of beginning farmers. The Rectors placed their farmland, infrastructure, and other assets into the new LLC and created a thoughtful, detailed LLC agreement with Noami Brautigam and James Gagne that allowed the new farmers (after a two-year trial period) to begin earning percentage ownership interests in the LLC.

All of the LLC members live on the property (in separate residences), and the Rectors are slowly releasing control and ownership over the land while still retaining access to the farm, receiving help maintaining the property and structures, and helping a new farming couple learn the business of farming. To read the full story, click here.

LLC Basics

Ownership of an LLC

- At any given time, each LLC member owns a certain percentage of the business via their “percentage membership interest.” Owning a percentage membership interest in an LLC is similar to owning a certain number of “shares” in a corporation. In fact, a percentage interest can also be reduced to a number of “units” in the LLC that add up to 100. Also, depending on the terms of the LLC operating agreement (discussed below), all or part of a member’s percentage interest in an LLC can be sold or gifted to another person or business.

LLC Operating Agreement

- An LLC Operating Agreement is a contract between LLC members that governs ownership and control of the business. An operating agreement is separate from the “Articles of Organization” or other form required to create an LLC with your state’s Secretary of State’s office. A detailed, thoughtful LLC operating agreement drafted by an experienced attorney is critical to a successful farm transfer. More information about LLC operating agreements is below.

Limited Liability Protection

- An LLC is so named because it provides some liability protection to its members for business actions taken by LLC members and debts incurred by the business. In other words, beyond the value of their percentage ownership interest in the LLC, the members of a properly-managed LLC are not usually personally liable for the debts and obligations of the business. This limited liability protection is often referred to as a “liability shield” because it can protect LLC members’ personal assets, like a home, a car, or personal bank accounts. However, LLC members are still always liable for personal wrongful conduct, like fraud or illegal acts. Also, LLC members can lose liability shield protection by, for example, signing a contract with a “personal guarantee” or by commingling business and personal monies.

Corporate Formalities Required

- An LLC is a business entity and must be treated as entirely separate from its individual members in order to maintain liability protection for LLC members. This can take some getting used to for farmers, who often view family life and farm operation as one holistic entity. For example, an LLC must have a bank account that is separate from individual members’ bank accounts. LLC members should also hold regular meetings, create meeting minutes (recording highlights of the meeting and who was present), keep records of major transactions, arrange appropriate tax filings, and make sure all farm business is done in the name of the LLC, not in the name of individual members. These formalities are not difficult to execute, but they can easily be put on the back burner by farmers with other pressing tasks to handle. Nevertheless, in order to maintain LLC liability protection, it’s important that farmers using an LLC model intentionally set aside time to make sure corporate formalities are handled appropriately. One way to make this part of a farming routine is to set up a calendar system and check in every month or every quarter with an LLC members meeting.

LLC Assets

- An LLC can only own assets (land, buildings, equipment, etc.) that are properly “placed into” (transferred to) the LLC. For example, in a farm transfer scenario, a newly-created LLC will not own the farmland until title to the land is officially transferred from the farmer owners (via the proper formal legal paperwork) to the LLC. Similarly, any farm buildings, farm equipment, farm animals, farm business name, rights to crops, and other assets must be formally transferred to the LLC. A business lawyer can help farmers make sure the appropriate assets are identified and that the formal transfer paperwork is completed correctly.

Corporate Farm Laws

- Your state may have a “corporate farm law” that is designed to protect family farms by limiting the ability of corporate entities (such as an LLC or a C-Corporation) to own farmland. For example, in Minnesota, all LLCs that own farmland must fill out a corporate farm law application, pay a $15 fee, and meet certain requirements in order to legally own farmland. Thus, before attempting an LLC-based farm transfer and creating an LLC to hold farmland, farmers should check their state’s laws and find out what requirements might apply.

LLC Operating Agreement

An LLC operating agreement is a private contract among LLC members that governs ownership and control of the business (including the farmland, buildings, equipment, animals, assets, etc.). An operating agreement is a private document entirely separate from the public-facing “Articles of Organization” or other form filed to create an LLC with your state’s Secretary of State’s office. A detailed, thoughtful LLC operating agreement drafted by an experienced attorney is critical to a successful farm transfer.

It is essential that farmers thinking about using an LLC to transfer farmland take the time to think through how to handle the management of the farm while it is in transition. The LLC operating agreement should set forth in writing the decisions that the senior and junior farmers make on a wide variety of topics, including at least the following:

How will the junior farmers pay for their initial percentage interest in the LLC? Will it be a down payment, sweat equity, or a combination? Will the senior farmers gift a percentage interest to the junior farmers (more common in a family transition)?

How will the junior farmers earn their increased percentage of LLC ownership over time? Will an additional percentage interest be tied to hours worked, certain milestones reached, farm profits, pre-set installment payments, or another mechanism? What happens if goals are not met or payments are not made?

How will the value of a percentage interest in the LLC be determined? Will the senior farmers hire an appraiser? Will the value be assessed only at the time the LLC is created, or will it be assessed each year as the transition gradually occurs? Will the value increase or decrease over time according to a formula, or in connection with another figure (inflation, average local land prices, interest rates)?

Will LLC members’ voting rights correspond to percentages of ownership? Will a 50 percent ownership equal a 50 percent voting interest, or will voting rights be separate from ownership of a percentage interest and be allocated separately?

What happens if one or more of the members involved in the farm transition realize that the situation isn’t working for them and they need to exit the LLC? Can the exiting farmer sell a percentage interest? Can they sell it only to a current member, or can they sell it to a third party? How much will their percentage interest be worth, and how and when will it be paid for?

Who is responsible for day-to-day decision making and daily activities on the farm?

Who makes “big” decisions for the farm, and what counts as a “big” decision? When is a vote of all the members required, and what percentage of votes is needed for a decision? Unanimous? Majority? Two-thirds? What happens if there is a disagreement or a deadlock?

If a farm is transitioning to children of the senior farmers, some of whom will run the farm and some who are “non-farming children,” what rights will the farming children have and what rights will the non-farming children have with respect to day-to-day management, profits, rights of access, and ability to sell the land outside the family?

Which assets of the senior farmers will be placed in the LLC, and which assets will remain personally owned by the senior farmers? Will the senior farmers live on the property? How will the existing buildings and equipment be used and/or transitioned to the junior farmers?

Will certain conservation measures or types of farming practices be allowed or required? Will diversification of income streams be allowed (such as creating a corn maze or a pizza farm business in addition to traditional crops or animals)?

If there is a dispute between the LLC members, how should it be handled? What happens if a married couple is involved in the transfer and a divorce occurs? What about the unexpected death of a member? In these situations, is mediation required? Which state’s laws will apply and what court would handle a lawsuit? If senior farmers plan to retire to Arizona while the junior farmers are in Nebraska, the cost of an out-of-state lawsuit could be prohibitive for one side or the other.

The questions above are just a subset of the universe of questions that should be answered by both the senior and junior farmers before embarking on an LLC-based farm transition. The questions that should be asked and the answers to these questions will differ in each individual situation. The answers to these questions should be written down and incorporated as part of the LLC operating agreement (with the help of an experienced attorney). An attorney should also insert operating agreement provisions that make the agreement legally effective and provide any additional protections for LLC members that are available over and above their state law’s baseline requirements.

For example, common business pitfalls (such as exiting members or disputes) should be anticipated and planned for at the outset of the relationship between the LLC members. Even with the best intentions and expectations, life happens.

Remember that without proper planning for common pitfalls, a treasured farm legacy could be lost.

Ultimately, you should consult with an attorney to ensure that your operating agreement suits the needs of all the members of the LLC and is legally effective.

Why Use An LLC For Farm Transfer?

When handled correctly, an LLC-based farm transfer has a number of benefits, including the following:

Flexibility

- LLCs are an extremely flexible type of business entity. LLC members can create a transition plan and business terms that suit their collective individualized wants and needs, as long as the senior farmers and junior farmers can come to a mutually beneficial agreement. For example, farmers have freedom to design: 1) the timing of the farm transfer; 2) whether the farm transfer will be immediate or gradual; 3) the way junior farmers will pay for farm ownership (cash, sweat equity, etc.); and 4) how the farm will be managed under joint ownership via the LLC.

Allows For Gradual Transfer

- Using an LLC to transfer a farm may be helpful if the parties want to transition the farm over a period of time instead of all at once (as a traditional sale requires). Under conditions stated in the LLC operating agreement, senior farmers can transfer ownership of LLC assets (farm land, buildings equipment, business accounts, etc.) to junior farmers bit by bit over a fixed period of time (months or years) in return for the junior farmers’ payment, work, or other valuable contribution. A gradual transfer can help ease newer farmers into farm management with help from experienced and (likely) more financially secure senior farmers. Senior farmers can also gradually gift percentage interests in an LLC to junior farmers (such as children or other prospective heirs interested in maintaining a family farm legacy).

- In most successful transfer cases, the junior farmers will eventually own 100 percent of the LLC, and will therefore own all of the farm assets that have been properly placed into the LLC. If farm assets have been properly “placed into” the LLC, junior farmers owning 100 percent of the LLC should own a complete farm business including land, buildings, equipment, animals, etc. (if that was the agreement among the LLC members).

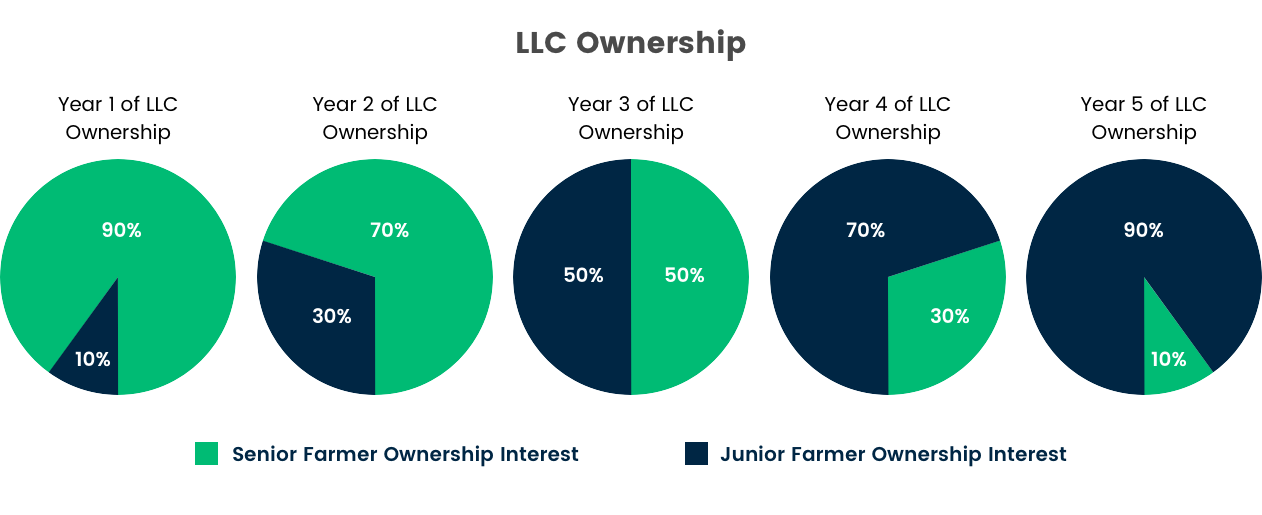

Senior Farmers Can Maintain Control While Transferring Ownership

- Transferring a farm through an LLC allows the senior farmers to retain as much or as little control in the farming operation during the transfer as the LLC members agree upon. This can be accomplished by separating ownership rights in the LLC from voting (governance) rights. For example, junior farmers could own a 90 percent ownership interest in the LLC but hold only 30 percent of the voting rights. In this example, the senior farmers would own a 10 percent ownership interest in the LLC but would hold 70 percent of the voting rights. This would put the senior farmers in ultimate control of the farm operation decision making while simultaneously allowing the junior farmers to have a larger income stream from the LLC.

Maximizing Land Access Opportunities For Junior Farmers With Limited Capital or Credit

- Using an LLC to transfer a farm in exchange for sweat equity, installment payments, or a combination of both may mean that new farmers with limited capital or credit would be able to access land without a bank mortgage loan. Or, new farmers might have the option to at least delay taking out a mortgage loan until after they have been part of the LLC for a period of time. These options make an LLC a particularly attractive option for new farmers who are initially unable to secure a bank mortgage loan for their farming operation or who would like to avoid carrying a heavy debt load.

LLC Operating Agreements Can Require Specific Farming Practices

- Through an LLC operating agreement (which is a private contract among the LLC members), members may create rules that member-farmers must agree to follow in order to use the land. Members of the LLC can incorporate conservation-related rules in the operating agreement that may contain restrictions on the use of the land. For example, members could agree to use best efforts to operate the farm business in a sustainable manner, specifically require certified organic farming practices, require particular kinds of soil maintenance, incorporate an NRCS (Natural Resources Conservation Service) plan, or come up with a detailed plan tailored to the particular piece of farmland and farmer goals.

Limited Liability

- An LLC provides some liability protection to its members for actions and debts of the business. Additionally, using an LLC structure helps limit individual LLC members’ liability for the actions of fellow LLC members. This limited liability set up is in contrast to a general partnership, for example, where each general partner is fully liable for the actions and debts of the other general partners – a risky setup if a partner turns out to be unwise or untrustworthy. Note that because an LLC’s liability shield is limited, and because LLC status cannot prevent a lawsuit (and associated attorney fees),

A farm LLC should always carry business insurance tailored to the specific needs of a farm operation.

Pass-Through Tax Status

- LLCs are automatically subject to federal “pass through” taxation status, which means the business itself does not pay federal income taxes on LLC business profits (although the business does need to file a federal tax form, called a K-1). The LLC profits “pass through” to the LLC members’ personal taxes. Each LLC member must report their percentage share of the LLC’s profits on their personal tax returns and pay federal income tax on their percentage of the profits. (This pass-through setup is in contrast to a C-Corporation, where both the corporation itself AND the individual shareholders must pay taxes – sometimes called “double taxation.”)

- Note, however, that depending on your individual tax situation, it might actually make financial sense to elect for your LLC to be taxed as an S-Corporation (check with your tax preparer and attorney); and that some states do require LLCs to pay state tax at the entity level (in addition to state income taxes on each LLC member’s share of the LLC profits). Check with your tax preparer to see what taxes you are required to pay and whether a different tax status might be advantageous for your business.

Ability To Combine With Other Transfer Tools

- LLCs can be used in conjunction with other legal tools, like wills, trusts, and leases, to transfer farms to the next generation.

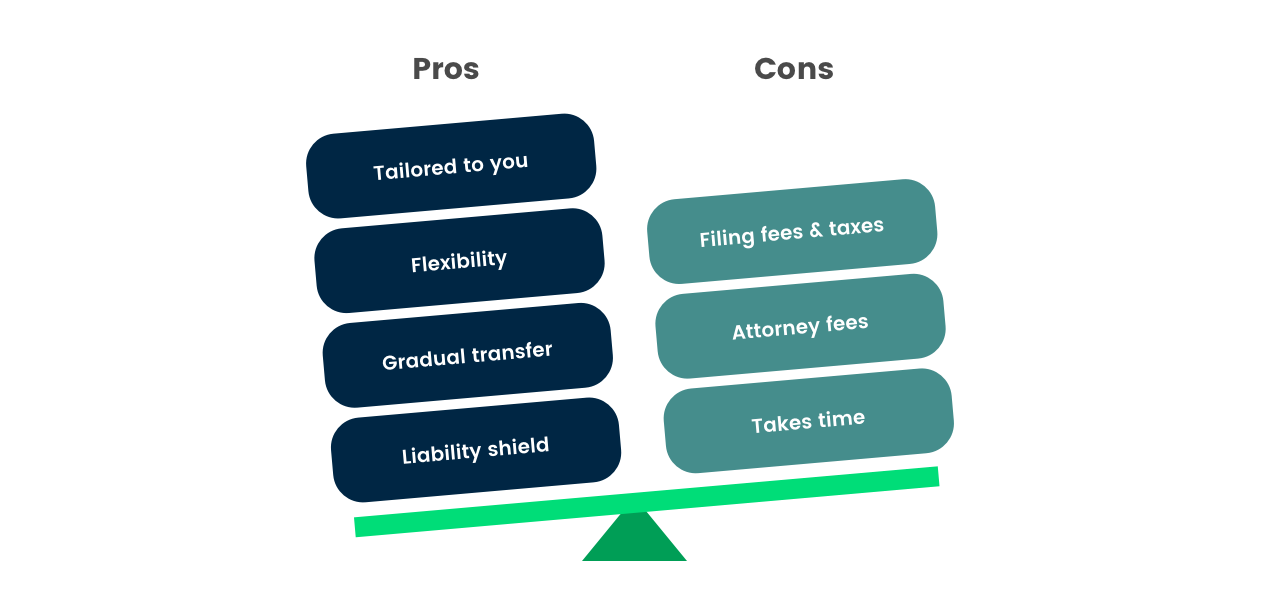

LLC Pros and Cons

LLC Pros and Cons

Note that the benefits described above will only exist with a properly structured LLC that is governed by a thoughtful, detailed operating agreement and LLC members who manage and run the LLC as a business entity that is entirely separate from personal assets.

LLC Transfer and Management Takes Time and Money

- A farm-based LLC transfer is not a simple, cheap, or one-time transaction. In contrast, setting up an LLC correctly and managing it properly over time requires both financial resources (to pay, for example, attorney fees and tax planning fees) and personal effort (the time it takes to work with an attorney, manage paperwork, negotiate an agreement, and navigate the long-term relationship with other LLC members).

New State LLC Fees and Taxes Can Add Up

- Besides income taxes, many states require LLCs to pay a filing or registration fee and/or annual renewal fees. For example, Michigan requires a $25 annual statement filing fee, Georgia requires an annual $50 registration fee, and Minnesota requires a $155 filing fee. New Mexico doesn’t require an annual registration fee, but LLC members must file a state Income and Information Return. Some states, like California, also require LLCs to pay franchise taxes. California’s franchise tax is a minimum of $800 per year, and increases as LLC revenue increases. Also, if the LLC has employees, you must pay state employer taxes, and if the LLC sells goods to state customers, you may have to collect and pay state sales taxes. For more details on state fees, see LLC Annual Report and Tax Filing Requirements: A 50-State Guide.

Without An Operating Agreement, Your Farm LLC Might Dissolve Automatically

- In some states, state laws establish that an LLC dissolves when a member leaves the LLC business. However, the state laws are usually just the default rule. Members of an LLC can often effectively address this issue by setting rules addressing under what conditions and how long an LLC will survive. For example, in Wyoming, if a member withdraws from the LLC, the LLC must dissolve unless all the remaining members of the LLC consent to continue under a right to do so stated in the LLC articles of organization. In Illinois, a dissociating LLC member must give the other members 30 days to decide to purchase the interest of the dissociating LLC member in order to avoid complete dissolution of the LLC. However, in Virginia, the dissociation of a member does not cause the LLC to dissolve. Check your state’s laws and make sure this issue is addressed in your LLC articles of organization or your LLC operating agreement, if necessary.

Bottom Line

- It’s important to remember that creating and running an LLC, even for farm transfer purposes, means that you are accepting certain financial, legal, tax, and filing obligations. However, depending on your farm transfer goals and resources, the benefits of an LLC-based farm transfer may be worth the money, time, and effort required. Farmers considering an LLC-based farm transfer should think about how well suited they are to manage a potentially complex LLC business, what financial resources are available to them, how important flexibility and tailoring are to their farm transfer vision, and whether other farm transfer options might make sense either instead of or in addition to using an LLC.

How Does An LLC Farm Transfer Work?

How Does An LLC Farm Transfer Work?

This section explains some of the mechanics that could be in involved in an LLC-based farm transfer. Please note that this section is meant to illustrate general concepts and does not include all of the options that might be available to farmers.

A farm transfer balances many nuanced and individualized considerations, and the flexibility of an LLC-based transfer allows an almost infinite array of possibilities. Accordingly, before choosing one or more specific transfer tools for your own farm transfer (LLC, gifting, trusts, etc.), it is important to assess your goals, values, and circumstances. It is equally important to consult with an attorney to ensure that the legal tools you intend to use will actually allow you to make your farm transfer vision a reality.

Example LLC Transfer Mechanics With Two Farming Couples

- Senior farmers create an LLC entity by filing Articles of Organization with the Secretary of State’s office.

- With the help of an attorney, senior farmers and junior farmers negotiate a detailed, written LLC operating agreement with (at least) ownership and transfer provisions and a buy-sell provision for exiting LLC members.

- Senior farmers and junior farmers sign the operating agreement, and senior farmers formally transfer agreed-upon farm assets from individual ownership to LLC ownership.

- Over time, junior farmers contribute sweat equity and/or money or other agreed-upon value to the senior farmers and thereby “purchase” and increase their percentage ownership interest in the LLC. As the junior farmers’ ownership percentage increases, the senior farmers’ percentage of ownership decreases. Transfer of a percentage interest in an LLC could also be done via gifting, wills, or trusts.

- Note that ownership rights can be separated from voting rights, so senior farmers could retain voting rights and some control over the operation without actually owning a corresponding equal percentage interest in the LLC. This option might be valuable for senior farmers who want to retain some say over how the operation is running but want to divest financial assets or allow junior farmers to have a larger share of LLC profits. Senior farmers should also consider how continued ownership via a gradual transition might affect their eligibility for Medical Assistance.

- Over a set period of time, junior farmers generally aim to acquire 100 percent ownership of the LLC and the senior farmers will have completely transferred their farm operation to the junior farmers.

How Junior Farmers Could Acquire LLC Ownership (Percentage Interest)

Under an operating agreement, senior farmers may allow junior (incoming) farmers to earn percentage interests in an LLC in a variety of ways, some of which are set forth below. Any of these specific methods could be combined to create an individualized solution tailored to the needs of the farmers involved in the transfer.

Installment Payments

- Junior farmers could pay installment payments to the senior farmers (similar to rent) for use of the farm property. However, instead of being treated as rent, the payments would be applied toward the purchase of a set percentage of the LLC owned by the senior farmers. For example, LLC members could agree that the junior farmers must pay $3,000 every three months, and at the end of the year the total of $12,000 ($3,000 x 4) would purchase an additional five percent ownership interest in the LLC from the senior farmers. In this way, the LLC setup is similar to a lease-to-own agreement where rent counts toward the eventual purchase price of the property. In an LLC-based transfer set up this way, the junior farmers build equity with each passing year (and senior farmers transfer equity each year), assuming installment payments are paid on time and all other conditions of the operating agreement are met.

Sell/Purchase

- The senior farmers sell percentage ownership interests to junior farmers, or junior farmers are expected to purchase a certain percentage ownership interest each year (at a certain price or according to an agreed-upon price formula).

Sweat Equity

- The junior farmers receive a certain percentage ownership interest in the LLC in exchange for working the land, rather than by making monetary payments. The parties to the arrangement determine ahead of time what percentage ownership interest is equal to a certain amount of farm labor (either by setting a certain amount, or by agreeing upon a formula). This could be tied to hours worked, outcomes achieved, or other measures. The important consideration here is that the LLC members clearly understand how and when a certain amount of work or defined outcome will result in the acquisition of a particular percentage of LLC ownership. Lack of clarity in this area could quickly lead to a dispute between the junior and senior farmers.

Gift

- Senior farmers can gift ownership interests in the LLC to their children (or other individuals) at once or over time. By gifting a percentage interest in an LLC, senior farmers can potentially receive the tax benefits of gifting while allowing their children (or other family or non-family gift recipients) to acquire equity without any cost. Note that there are federal tax limits on the amount that any party can gift annually, so gifting ownership interests may require strategic planning, like the disbursement of interests over several years. For more details on gifting requirements, visit the gifting page. Additionally, note that any recipient of an LLC interest will generally need to pay taxes each year on any profits that correspond to their percentage interest in the LLC.

Will

- Senior farmers can disburse LLC interests through their will. However, if the senior farmers pass away while retaining ownership interest in the LLC, that interest will generally have to go through the probate process, since wills must go through probate. For more details, visit the wills page.

Trust

- Senior farmers can set up a trust to transfer a percentage interest in the LLC during their life or at their death. The advantage to transferring a percentage interest in an LLC through a trust, rather than a will, is that when senior farmers pass away with a percentage ownership interest remaining in the trust, the trust does not have to go through the probate process. Instead, the assets within a trust generally pass directly to its beneficiaries. For more details, visit the trusts page or the probate section on the wills page.

Multiple LLCs Can Be Used For Transfer

An LLC transfer plan can involve one or more LLCs. In many situations, one LLC could effectively transfer the entire operation from the senior farmers to the junior farmers. Sometimes, however, using more than one LLC might make sense if assets (like land, buildings, equipment, etc.) are best served by being held within separate LLCs. An experienced attorney can help farmers make and execute these more complex business decisions.

How and whether to use one or more LLCs for farm transfer is a highly individualized strategic decision that should only be made with the help of an experienced attorney.

How An Attorney Can Help

How An Attorney Can Help

The Attorney’s Role

It’s not an attorney’s job to make decisions for farmers or to set farm transfer goals. Instead, attorneys can provide information about pros and cons of different options, advice about what is common versus unusual, fair versus unfair, etc. Attorneys can help farmers understand the universe of possible farm transfer goals and help narrow down individual options so that farmers can make final decisions.

How An Attorney Can Help With LLC-Based Farm Transfers

- Understand the process of creating and managing an LLC.

- Help determine which state law obligations (fees, filings, default rules) apply to your LLC.

- Properly set up one or more LLCs to be used in a farm transfer.

- Draft a thoughtful, tailored LLC operating agreement between the LLC members that governs how the farm will be managed and transferred.

- Make sure that your farm assets are properly “placed into” your LLC.

- Create a fair and reasonable course of action in the event of an LLC member’s exit.

- Include sustainability and land use requirements related to farm management.

- Make sure you are maintaining your liability shield by running the LLC correctly.

- Help you find farm business liability insurance.

- Resolve disputes among LLC members or help you protect yourself in a dispute.

Additional Resources

Additional Resources

- LLC Creation Checklist (Farm Commons)

- LLC Annual Report and Tax Filing Requirements: A 50-State Guide (NOLO)

Related Legal Tools

Footnotes

1. For example, in New Hampshire, an LLC has to pay a business profits tax if it has a gross income of more than $50,000 before expenses. See http://www.revenue.nh.gov/assistance/tax-overview.htm#profits. Additionally, New Hampshire also imposes a business enterprise tax on LLCs with gross business receipts for more than $200,000, or if the tax base exceeds $100,000. See http://www.revenue.nh.gov/assistance/tax-overview.htm#enterprise. Also, in California, if an LLC makes more the $250,000 per year, the state requires the business to pay income taxes.

The Center for Agriculture and Food Systems is an initiative of Vermont Law School, and this toolkit provides general legal information for educational purposes only. It is not meant to substitute, and should not be relied upon, for legal advice. Each farmer’s circumstances are unique, state laws vary, and the information contained herein is specific to the time of publication. Accordingly, for legal advice, please consult an attorney licensed in your state.