Heirs’ Property

- Overview

- How Heirs’ Property Works

- Amount of Land Owned as Heirs’ Property

- Challenges for Heirs’ Property Owners

- Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act

- Importance of Wills and Estate Planning

- Understanding the Legal Issues in Your State

- State Incentives to Clear Title and Facilitate Property Transfer: A Focus on Vermont

- Heirs Property Case Studies

- A Lawyer’s Suggestions for Heirs’ Property Owners

- How An Attorney Can Help

- Organizations Providing Direct Assistance to Heirs’ Property Owners

- Additional Resources

Overview

Overview

Heirs’ property is property passed to family members by inheritance, usually without a will, or without an estate planning strategy. Typically, it is created when land is passed from someone who dies “intestate,” meaning without a will, to their spouse, children, or others who may be legally entitled to the property. (See box below regarding how a will can create heirs’ property too.) If the property is inherited without a will, the heirs own the property as tenants in common, which means they each own an interest in the undivided property. These interests may be equal or the heirs may inherit different percentages of the property, depending on state law. In other words, rather than each heir owning their own individual lot or piece of the property, they each own an interest in the whole property. Unless the heirs go to the appropriate administrative agency or court in their locality, and have the title or deed to the land changed to reflect their ownership, the land remains in the name of the person who died. For the heirs, owning property as tenants in common without clear title leads to many problems, which are discussed in detail below.

How A Will Can Create Heirs' Property

A person with a legally valid will can designate heirs to inherit their real property. If multiple heirs are designated, this creates what the law calls a co-tenancy. Two forms of co-tenancy can arise in the context of heirs property—tenancy in common and joint tenancy. Unless specifically designated, multiple heirs receiving one parcel of real property from a will will inherit as tenants in common. Sometimes, a will may specifically designate multiple heirs to receive the property as joint tenants with a right of survivorship.

Joint Tenancy

In a joint tenancy, each joint tenant is considered to have an equal, undivided interest in the whole unless state law provides otherwise. Generally, joint tenants are required to seek consent from the other joint tenants before taking an action that impacts the property. If a joint tenant takes an action that impacts the property without the consent of the other joint tenants, that can break the joint tenancy and may convert it into a tenancy in common. Joint tenancies also include the right of survivorship meaning that when one joint tenant dies, the whole property passes to the other joint tenant.

Tenancy in Common

A tenancy in common is the default form of co-tenancy, meaning that unless a will specifies a joint tenancy, if the will leaves property to more than one person, they own it as a tenancy in common. And if property passes to multiple heirs without a will, based on a state’s intestacy laws, those heirs own the property as tenants in common. When heirs own property as tenants in common, they may have equal or unequal shares in the property. When one of them dies, their share passes to their heirs, rather than their existing co-tenants.

In both cases, each tenant owns an undivided interest in the whole property. Either way, if the person who died designates more than one heir to take the property, and title is not legally transferred from that person to the current heirs, it becomes heirs’ property, and those heirs are subject to the legal problems set forth below.

Heirs’ property has been a significant driver of land loss for particularly African American farmers in the United States. For example, in parts of South Carolina and Georgia, the Coastal Community Foundation of South Carolina estimated that 14 million acres of heirs’ property has been lost since the Civil War.

Heirs’ property is also an issue for many communities in Appalachia, Latine communities in the Southwest, and Indigenous communities living on reservations. Ultimately, heirs’ property can increase land insecurity for entire communities and impede the transfer of intergenerational wealth while also creating challenges for access to loans and government grants and assistance.

How Heirs' Property Works

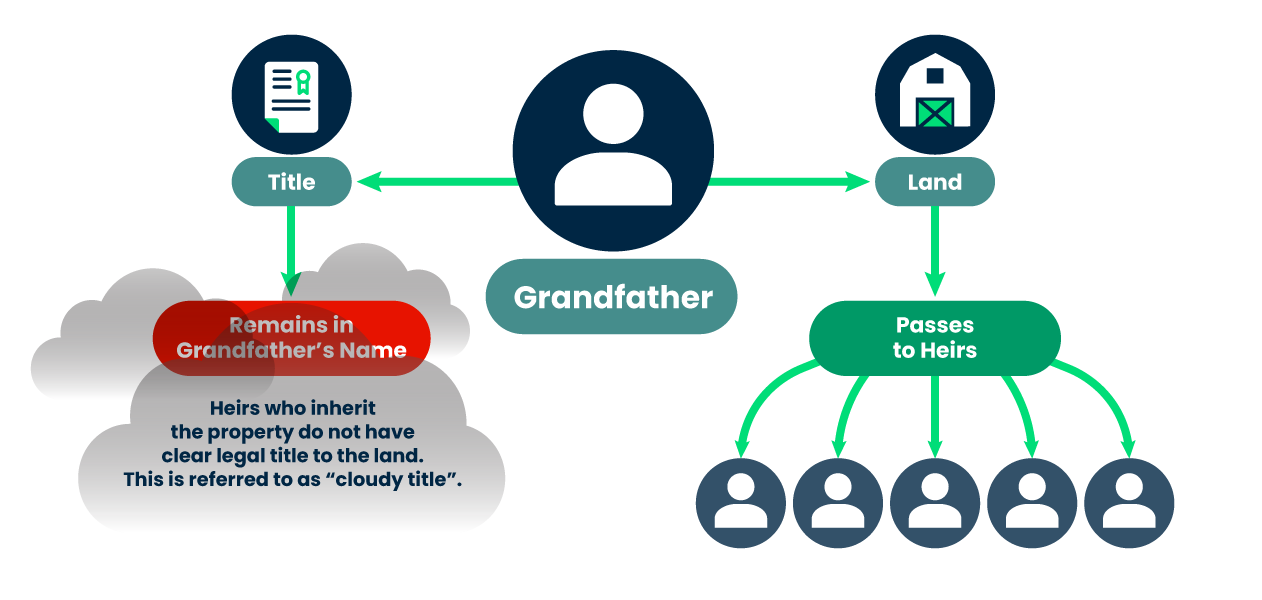

State “intestate succession” laws govern who are heirs to property when someone dies without a will. In the US, every state’s law provides that family members who inherit property from someone who dies without a will own the property as tenants in common. If the tenants in common do not change the deed to the property to reflect that they own it, the property remains in the name of the deceased person rather than those who inherited it.

If the original heirs then die without a will, and their descendants inherit the original heirs’ interests in the land, each additional heir now has an ownership interest in the property. After a couple generations, there could be 25 heirs, each having an ownership interest in the land. After another generation, there could be 50 owners. The deed to the land will still show the original ancestor, now perhaps the current heirs’ great grandfather, as the owner. These 50 heirs who each hold an interest in the land now have a “cloudy title,” since the deed remains in the name of the great grandfather who has long since died. This ownership structure is problematic for the landowners, for reasons explained below.

Amount of Land Owned as Heirs' Property

There are numerous studies attempting to demonstrate how much heirs’ property exists both regionally and across the US. One recent national estimate shows that there are approximately 444,172 parcels of land, totaling 9,247,452 acres, that qualify as heirs’ property in the United States excluding the territories.1 This property is valued at $41,324,314 billion.

Recent estimates of heirs’ property amounts and values build off many decades of work performed by other organizations and entities: In 1980, the Emergency Land Fund estimated that 41 percent of land owned by African Americans in the Black Belt South was held as heirs’ property, for a total of 3.8 million acres.2 There have been a few more recent localized studies performed: one study from 2010 looked at 365 counties in 11 southern states where African Americans made up 25 percent or more of the population. This study extrapolated from the data collected and determined that heirs’ property comprised 1.6 million acres valued at $6.6 billion.3 The Federation of Southern Cooperatives estimates that 60 percent of African American-owned land is held as heirs’ property. Some media outlets have estimated that a third of African American-owned land in the south is held as heirs’ property—3.5 million acres valued at approximately $28 billion.4

A recent regional study, commissioned by the National Policy Research Center at Alcorn State University in Mississippi, conservatively estimates that across the 14 southern states studied, there are 579,000 parcels of heirs’ property totaling 6.8 million acres, with a value of $47.3 billion.5

Studies vary depending on their methodology. It is challenging to obtain specific data because every state, and each county within each state, compiles real estate ownership data differently. Most people who have studied heirs’ property agree that there are millions of acres in the U.S. held as heirs’ property, worth billions of dollars, in both urban and rural settings.

Appalachia is known as a region where there are substantial amounts of heirs’ property. In 2005, B. James Deaton, an agricultural economist, estimated that in a single county in Appalachian Kentucky between 14-24 percent of property was held as heirs’ property.6 Currently, there are broader studies underway to determine the amount of land in Appalachia held as heirs’ property.7

Indigenous people also hold a significant amount of land in the United States as heirs’ property, or fractionated land. The Dawes Severalty Act of 1887 (the General Allotment Act) allowed for the division of Native American reservations into allotments for individual tribal members and made inheritance of these plots of land subject to state law. However, Indigenous people did not treat land as a commodity, were not legally permitted by the U.S. to use wills to transfer land until 1910, and were unfamiliar with U.S. legal mechanisms such as wills.8 If someone died “owning” an allotment, their heirs were left the property via intestate succession laws of the state, and title remained in the name of the ancestor who died, creating significant amounts of heirs’ property, known as fractionated land.9

African American rural landholdings have significantly declined over the last 100 years from the almost 16 million acres of farmland operated by farmers in 1910 (14 percent of all farm operators), to less than 3 million acres operated by African American farmers in 2017 (1.5 percent of all farm operators).10 A number of factors have contributed to this loss:

- African Americans fleeing their land and migrating north and west to avoid Jim Crow laws and lynchings in the south;

- The lack of access to capital and credit and high rates of foreclosures, spurred by discrimination by USDA and its local county committees;

- The illegal takings of land by partition sales, fraudulent tax sales and other forced land sales, including the theft of a substantial amount of land held as heirs’ property; and

- Deceptive practices and the withholding of legal information by unscrupulous sheriffs, lawyers, and judges.11

The rate of African American land loss has been far greater than for other racial and ethnic groups in the same time period. It remains a continuing and systemic problem, as it is a significant factor in the wealth gap between white and African American populations.

Challenges for Heirs' Property Owners

There are numerous challenges for landowners who are heirs’ property owners, including the following:

Legal Title Implications

The individual heirs who inherit real estate as heirs’ property do not have clear legal title to the land because the deed to the land remains in the deceased ancestor’s name. Since ownership of heirs’ property is transferred through inheritance and often there has been no recorded change in the name of the owner, it is difficult to prove ownership by the heirs. This is referred to as “cloudy title.” Heirs’ property owners with cloudy title cannot use the property as collateral for a mortgage or other type of loan for farm operating expenses or equipment, and cannot access government programs that require proof of ownership of land, including Farm Service Agency loans, USDA programs, or FEMA disaster recovery and relief assistance.

Additionally, it can be difficult to sell timber or other natural resources on the land to generate income, as many companies often require proof of ownership.

FARM AND TRACT NUMBER REQUIREMENTS

After the 2018 Farm Bill, a package of legislation which governs many aspects of food and agricultural policy in the US, USDA’s Farm Service Agency developed rules allowing heirs’ property owners to obtain a farm and tract number, even if they hold cloudy title to their property. This is significant because USDA requires farmers to have a “farm number” to participate in and benefit from many of the agency’s programs. Having a farm number allows a farmer to be part of the USDA system and receive notice of new programs and other opportunities, get technical assistance from USDA, obtain loans, and take advantage of USDA’s many programs. It also allows farmers to participate in elections for local USDA county committees, which determine local farmers’ ability to obtain loans, along with other matters. The Farm Service Agency has issued guidance that sets forth rules regarding how different types of heirs’ property owners can obtain a farm number by showing documentation that they are the farm’s owner or operator.

Another positive development for heirs’ property owners is that the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has also developed guidelines for its agents to accept documentation from heirs’ property owners that will allow them to get disaster relief. This is critical given the prevalence of more extreme weather events.

Implications for Tenants in Common

In the U.S., each state’s law considers heirs’ property owners who inherit under the intestacy laws to be “tenants in common.” The laws governing tenants in common generally require full agreement among the heirs for any commercial activity on the land, such as timber sales, development, or leasing. This can be extremely difficult to obtain, especially if there are multiple generations of heirs who must come to agreement. It can be hard to locate all the heirs, and even if they are found, families often cannot agree on what to do with the land. The USDA’s Farm Service Agency runs an Agricultural Mediation Program that can help with family disputes regarding heirs’ property.

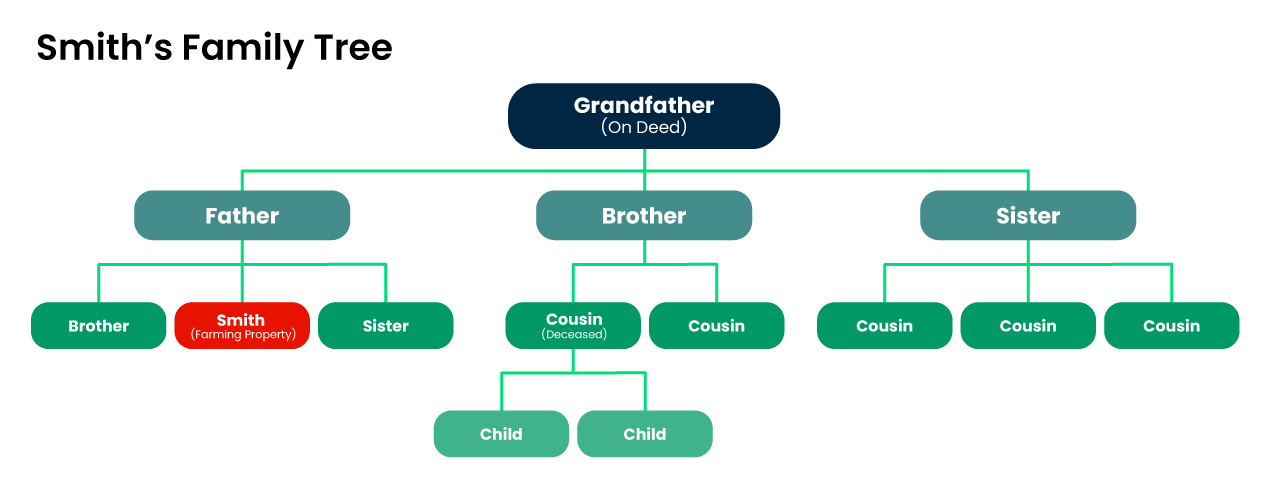

As an example, assume 63-year-old Smith farms on land they have lived on for their entire life. Smith wants to get a farm and tract number from USDA, which is necessary to qualify for a loan from USDA’s Farm Service Agency to buy seed and other items needed to plant their crops for the season. However, the land was originally owned by Smith’s grandfather, who left it to Smith’s father and two siblings, all of whom are deceased. Smith’s father’s two siblings each had several children; one cousin died, and Smith believes the rest of the cousins are alive, but does not know where they are. Smith’s brother and sister moved away years ago, but they all remain in touch. The last deed to the land on record lists Smith’s grandfather as the owner because the family did not have an attorney clear the title after Smith’s grandfather, father, and the father’s remaining siblings died.

Because Smith has cloudy title to the land and there are numerous other owners of the land from whom Smith has to obtain consent to do business, it is very difficult to make decisions that could generate income from the land. For example, Smith cannot participate in most USDA programs, obtain USDA or Farm Service Agency loans, enroll in commodity support programs or disaster assistance programs, or get technical assistance. Additionally, Smith cannot use the property as collateral for any loans from banks or other financial institutions. Put simply, Smith cannot participate in any activity that requires demonstration of clear legal title or sign anything as the “owner.”

Partition Sales

Owners of heirs’ property are particularly vulnerable to losing their land because they are subject to a legal action called a “partition action.” State law generally provides that because heirs’ property owners who have inherited through intestacy laws are tenants in common, any of the co-owners of heirs’ property can bring an action in court to obtain an order establishing the value of their interest in the property. Once a partition action is filed, a court can order a “partition in kind” or “partition by sale.” A partition in kind results in a court ordering the physical division of the land equitably and proportionate to the value of each owners’ share. Generally, courts are supposed to favor partition in kind when possible to honor any sentimental attachment to the land. When a court orders partition by sale, the property is sold to the public, usually by forced sale at an auction, and the owners of the property lose their family legacy and generally receive a small percentage of what the land is worth, which is often much less than the property’s fair market value.

Although most states have a legal preference for partition in kind, many courts have ordered partition sales even where the property can be divided. Even if 50 heirs own a tract of land as tenants in common, the owner of one 1/50th interest can file a partition action in court and ask the court to order a forced sale of the property, which is likely to result in a sale of the property at a very low price at auction.

For example, if one family member is financially vulnerable and has no connection to the land or to the family living on and farming on the land, and a real estate developer offers that family member a few thousand dollars for their share, that offer could be very attractive. Many heirs’ property owners do not know that if they sell their share to the real estate developer, the developer can ask a court to order the sale of the entire property. Unfortunately, this type of event is quite common.

Partition sales have proved devastating to heirs’ property landowners, resulting in forced sales of millions of acres of property and the loss of a tremendous amount of land, wealth, and family legacy.

Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act

The Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act (UPHPA), completed by the Uniform Law Commission in 2010, contains legal protections for heirs’ property owners designed to address the devastating effect of partition sales. The UPHPA restructures the way partition sales occur in states that adopt the act, and generally includes three major reforms to partition law:

- If a co-owner brings a partition action in court, the court must provide an opportunity to the other co-owners to buy out the co-owner who brought the action. Significantly, the value of the share of the co-owner who brought the partition action is determined by multiplying the fair market value of the property as determined by an appraiser by the person’s percentage of interest in the property.

- If there is no buyout, then the law provides a preference for the court to order a partition in kind and divide the property, rather than order a sale. The law requires courts to take into account factors other than economic, such as the value of family heritage, historical value of the property, or the impact of the sale on those living on the property.

- If a partition in kind is not ordered, the UPHPA requires the court to sell the property at a market sale, not at an auction sale, and specifies a process for the property to be appraised and sold for its fair market value. The law is designed to preserve and maximize the wealth generated for the heirs’ property owners by the sale.

As of May 2025, 24 states and the Virgin Islands have passed the UPHPA, including Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Connecticut, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Maryland, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, New York, South Carolina, Texas, Utah, Virginia and Washington.12 The passage of the act in all 50 states could mitigate the impact of partition sales on heirs’ property owners.

Importance of Wills and Estate Planning

Overall, a substantial number of Americans do not have wills or other estate plans; studies show the rate of dying without a will (“intestacy”), is between 40 and 70 percent, depending on factors such as race and income level.

Estate planning and will making are critical to avoid the challenges for heirs’ property owners outlined above.

Understanding the Legal Issues in Your State

The following fact sheets aim to prevent the loss of land owned as heirs’ property in specific states. Each examines state laws that are relevant to heirs’ property owners, and outlines steps owners can take to resolve property issues before seeing an attorney.

Each fact sheet also addresses relevant legal issues in a given state, including: 1) how to identify legal heirs of the original ancestor who owned the land; 2) state partition law; 3) state law that permits tax foreclosures, i.e., the sale of land due to unpaid property taxes; and 4) state law addressing adverse possession and condemnation (terms defined in the glossary in each resource).

In addition to heirs’ property owners, these fact sheets may be useful to professionals assisting heirs’ property owners, such as lawyers, nonprofit and community development advocates, and cooperative extension agents.

State Incentives to Clear Title and Facilitate Property Transfer: A Focus on Vermont

This issue brief assesses how state incentives to clear title and make it easier to transfer property reduces the amount of heirs’ property in Vermont. Allowing the use of deeds to avoid probate, implementing a property tax system that incentivizes clearing title, and establishing methods for lawyers to correct clouded title issues that do not require a full probate process are a few of the legal processes discussed. These policies could serve as examples for other similarly rural states with heirs’ property issues.

Heirs Property Case Studies

Heirs Property Case Studies

The Wright Family's Story

The Wrights are a large family, managing a sizeable plot of heirs’ property that has been in their families for decades. Although this story is still unfolding, the Wrights have a couple of things working in their favor: they have a representative structure for making decisions as a group, and they retained an attorney prior to any conflict arising regarding the land. With the help of students from two law school clinics, the Wrights are optimistic that transferring their interests into a legal entity will allow the family to keep the property secure for generations to come.

Janice's Story

Disputes between family members present significant barriers to families solving heirs’ property issues by clearing title. In this particular matter, family conflict was the main source of friction. Although this matter was ultimately resolved satisfactorily to all parties, it demonstrates the issues that arise when family property issues are left unaddressed for a long period of time.

A Lawyer’s Suggestions for Heirs’ Property Owners

Click here to read an essay by Mavis Gragg, attorney, and CEO & cofounder of HeirShares.

How an Attorney Can Help

How an Attorney Can Help

How An Attorney Can Help With Heirs' Property

Lawyers who help families with heirs’ property must have experience in trusts and estates, real estate, and business law. Before hiring an attorney, families should attempt to find out the identities of the heirs, create a family tree, and collect all information possible regarding the land and its recorded owners. Family bibles where handwritten records of births and deaths have been kept, birth certificates, and death certificates are all relevant. In order to prove the identity of the heirs, an heirship affidavit may have to be filed with the court, and the family will have to demonstrate it made a diligent search and inquiry for all the heirs. A lawyer can review documents provided, review any available public records, discuss particular issues regarding the family’s land, and recommend next steps. These recommendations should include estimated costs for each stage of resolving the heirs’ property issues, and what the family can do to prevent further distribution of heirs’ property, including perhaps creating a trust, an LLC, or another business entity to hold the land.

USDA's Agricultural Mediation Program

The USDA’s Farm Service Agency (FSA) runs an Agricultural Mediation Program which can be used by heirs’ property owners to mediate family disputes. The FSA grants funds to relevant state agencies to support mediation between those involved in many kinds of disputes related to agricultural issues, including USDA decisions on loans, conservation programs, wetland determinations, and rural water loan programs. Other disputes that can be mediated include lease issues between a landlord and tenant, family farm transition issues, farmer-neighbor disputes and family disputes regarding heirs property. For example, if a lender denies a farmer a loan, they may request mediation before resorting to an administrative appeal within the relevant agency. Mediation helps producers avoid significant costs associated with litigation. A list of state certified agricultural mediation programs is here:

Organizations Providing Direct Assistance to Heirs’ Property Owners

Organizations Providing Direct Assistance to Heirs’ Property Owners

Black Family Land Trust: bflt.org

Center for Assistance to Families: https://mycaf.org/

Center for Heirs Property Preservation: heirsproperty.org

Community Legal Services – mid-Florida: clsmf.org

Federation of Southern Cooperatives/Land Assistance

Fund: federation.coop

Florida A&M University, Cooperative Extension Program: cafs.famu.edu/outreach

Georgia Heirs’ Property Law Center: gaheirsproperty.org

HeirShares: heirshares.com

Indian Land Tenure Foundation: iltf.org

Jacksonville Area Legal Aid: jaxlegalaid.org

Land Loss Prevention Project: landloss.org (North

Carolina)

Legal Aid of North Carolina: legalaidnc.org

Legal Aid Society of Palm Beach County: https://legalaidpbc.org

Legal Services Alabama: legalservicesalabama.org

Legal Services of Eastern Missouri: https://lsem.org

Legal Services of Greater Miami, Inc.: legalservicesmiami.org

Legal Services of North Florida: www.lsnf.org

Livelihoods Knowledge Exchange Network (LiKEN Knowledge) (KY): likenknowledge.org/

Louisiana Appleseed Center for Law & Justice: louisianaappleseed.org

McIntosh SEED: mcintoshseed.org

Mexican American Unity Council: mauc.org/

Middle Georgia Access to Justice Council, Inc.: mgajustice.org

Mississippi Center for Justice: mscenterforjustice.org

New York City Bar Justice Center, Homeowner Stability

Project: citybarjusticecenter.org/projects/homeowner-stability-project

Prairie View A&M University: pvamu.edu

Roanoke Electric, Inc.: roanokeelectric.com

Southern University Law Center: sulc.edu

Sustainable Forestry and African American Land Retention

Program: sflrnetwork.org (includes

links to the eight partners working with landowners)

The KKAC Organization, Inc.: kkac.org

The Limited Resource Landowner Education and Assistance

Network

Three Rivers Legal Services, Inc.: https://www.trls.org/

University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff: uapb.edu

Winston County Self Help Cooperative: wcshc.com

Resources

Resources

- Thomas W. Mitchell, Historic Partition Law Reform: A Game Changer for Heirs’ Property Owners (2019), https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2313&context=facscholar.

- Conner Bailey et al., Heirs’ Property and Persistent Poverty among African Americans in the Southeastern United States, in Heirs’ Property and Land Fractionation: Fostering Stable Ownership to Prevent Land Loss and Abandonment (Cassandra J. Gaither et al. eds., 2019).

- Cassandra Johnson Gaither, “Have Not Our Weary Feet Com to the Place for Which Our Fathers Signed?”: Heirs’ Property in the United States, United States Dep’t of Agric. Forest Serv. (2016), https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/gtr/gtr_srs216.pdf.

- The Emergency Land Fund, The Impact of Heir Property on Black Rural Land Tenure in the Southeastern Region of the United States (1980)

- Michelle Chen, Black Lands Matter: The Movement to Transform Heirs’ Property Laws, The Nation (Sept. 25, 2019), https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/heirs-property-reform/.

- Faith Rivers, Inequity in Equity: The Tragedy of Tenancy in Common for Heirs’ Property Owners Facing Partition in Equity, 17 Temp. Pol. & Civ. Rts. L. Rev. 1 (2008).

- 1910 Census: Volume 5. Agriculture, 1909 and 1910, General Report and Analysis, United States Census Bureau (1913), https://www.census.gov/library/publications/1913/dec/vol-5-agriculture.html.

- Edward Pennick & Monica Rainge, African-American Land Tenure and Sustainable Development: Eradicating Poverty and Building Intergenerational Wealth in the Black Belt Region, in Heirs’ Property and Land Fractionation: Fostering Stable Ownership to Prevent Land Loss and Abandonment (Cassandra J. Gaither et al. eds., 2019).

- Tadlock Cowan & Jody Feder, Cong. Research Serv., RS20430, The Pigford Cases: USDA Settlement of Discrimination Suits by Black Farmers (2013).

- When Black Farmers Prevailed: Remembering the Historic Pigford Case, RAFI-USA (Aug. 13, 2015), https://www.rafiusa.org/blog/tbt-when-black-farmers-prevailed-remembering-the-historic-pigford-case/.

- 2017 Census of Agriculture – UNITED STATES DATA, USDA, Nat’l Agric. Stats. Serv. 72–75 (2017), https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2017/Full_Report/Volume_1,_Chapter_1_US/st99_1_0061_0061.pdf.

- Abril Castro and Zoe Willingham, Progressive Governance Can Turn the Tide for Black Farmers, Ctr. for Am. Progress (Apr. 3, 2019, 9:03 AM), https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2019/04/03/467892/progressive-governance-can-turn-tide-black-farmers.

- Leah Douglas, Deep in the farm bill, a step forward for black farmers on heirs’ property, Food & Env’t Reporting Network (July 24, 2018) https://thefern.org/ag_insider/deep-in-the-farm-bill-a-step-forward-for-black-farmers-on-heirs-property/.

- Thomas W. Mitchell, Reforming Property Law to Address Devastating Land Loss, 66 Ala. L. Rev. 1 (2014).

- Thomas W. Mitchell, From Reconstruction to Deconstruction: Undermining Black Landownership, Political Independence, and Community through Partition Sales of Tenancies in Common, 95 Nw. U. L. Rev. 505 (2001).

- They Stole Our Land, by Todd Lewan and Dolores Barclay, AP series

- Todd Lewan & Dolores Barclay, ‘When They Steal Your Land, They Steal Your Future,’ Associated Press (Dec. 2, 2001, 12:00 AM), https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2001-dec-02-mn-10514-story.html.

- Heirs Property Myths & Facts, Georgia Heirs Property Law Center, https://www.gaheirsproperty.org/myths-facts-about-heirs-property (last visited Jan. 24, 2021)

- Nathan Rosenberg & Bryce Wilson Stucki, How USDA distorted data to conceal decades of discrimination against Black farmers, The Counter (June 26, 2019, 7:00 AM), https://thecounter.org/usda-black-farmers-discrimination-tom-vilsack-reparations-civil-rights/.

Related Legal Tools

Footnotes

- Dobbs, Rebecca G. & Cassandra Johnson Gaither, How Much Heirs’ Property Is There? Using LightBox Data to Estimate Heirs’ Property Extent in the United States, Journal of Rural Social Sciences. Vol 38, issue 1 (2023), https://open.clemson.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1013&context=jrss.

- The Emergency Land Fund, The Impact of Heir Property on Black Rural Land Tenure in the Southeastern Region of the United States 50, 62–63 (1980); Thomas W. Mitchell, Destabilizing the Normalization of Rural Black Land Loss: A Critical Role for Legal Empiricism, 2005 Wis. L. Rev. 557, 582 (2005); Cassandra Johnson Gaither, “Have Not Our Weary Feet Com to the Place for Which Our Fathers Signed?”: Heirs’ Property in the United States, United States Dep’t of Agric. Forest Serv. (2016), https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/gtr/gtr_srs216.pdf.

- Gaither collects the data that existed in 2016 in her book produced by the Forest Service. Gaither, supra note 1, at 13.

- Michelle Chen, Black Lands Matter: The Movement to Transform Heirs’ Property Laws, The Nation (Sept. 25, 2019), https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/heirs-property-reform/.

- (Forthcoming)

Thomson R., Bailey C. & Gunroe, A., Quantifying Heirs’ Property Across

the Deep South: A Geospatial Approach. US

Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Southern Research Station. - Gaither, supra note 1.

- Liken Knowledge, a community based organization based in Kentucky, is spearheading an heirs’ property project to attempt to determine the frequency of occurrence of heirs’ property. Heirs’ Property Project, Liken Knowledge, https://likenknowledge.org/projects/heirs-property-project/.

- Gaither, supra note 1.

- For more information regarding heirs’ property and the complicated land issues facing Native Americans, see Indian Land Tenure Foundation, at https://iltf.org/land-issues/.

- 2017 Census of Agriculture – UNITED STATES DATA, USDA, Nat’l Agric. Stats. Serv. 72–75 (2017), https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2017/Full_Report/Volume_1,_Chapter_1_US/st99_1_0061_0061.pdf.

- Thomas W. Mitchell, Historic Partition Law Reform: A Game Changer for Heirs’ Property Owners 65 (2019).

- Partition of Heirs Property Act, Uniform Law Commission, https://www.uniformlaws.org/committees/community-home?CommunityKey=50724584-e808-4255-bc5d-8ea4e588371d (last visited Jan. 24, 2021).

The Center for Agriculture and Food Systems is an initiative of Vermont Law School, and this toolkit provides general legal information for educational purposes only. It is not meant to substitute, and should not be relied upon, for legal advice. Each farmer’s circumstances are unique, state laws vary, and the information contained herein is specific to the time of publication. Accordingly, for legal advice, please consult an attorney licensed in your state.