Long-Term Healthcare Planning

- Overview

- What Is Long-Term Healthcare?

- Why Is It Important?

- How Does Long-Term Healthcare Planning Relate to Farm Transfer?

- How Can Farmers Pay For Long-Term Healthcare?

- What Is The Difference Between Medicare And Medicaid?

- How Can Farm Transfer Affect Medicaid Eligibility?

- How An Attorney Can Help

- Additional Resources

Overview

Overview

Long-term healthcare planning is important for all people, including farmers. The majority of Americans will require an average of five years of care near the end of their lives. In a farm succession situation, it is all the more important to have a plan because the high cost of care. Planning can ensure access to health care services. Not having a long-term healthcare plan could result in the loss of land or other farm assets that must be sold in order to cover the high costs of care. It’s best to consult with an elder law attorney and/or financial planner about long-term healthcare planning long before you or your family member might need care.

What is Long-Term Healthcare?

Long-term healthcare is assistance provided to the elderly and cognitively impaired who have difficulty performing daily tasks of living, such as eating and drinking, bathing and toileting, dressing and grooming, and sitting and standing. Long-term care also receives a special designation by public programs and insurance companies (versus standard healthcare). Generally, a person’s eligibility for coverage is based upon their ability to perform the “activities of daily living,” as defined by each individual program or policy.

Farmer Spotlight:

Sunbow Farm

New farmers Yadira and Nate agree that a major benefit of their gradual farm transfer agreement is stepping into Harry MacCormack and Cheri Clark’s successful 40-year organic farming business.

Real Talk From Elder Law Attorney Donald Sienkiewitz

Long-term care planning is a VERY complex legal and financial subject

Unfortunately, your long-time family lawyer, your banker, and your insurance brokers are unlikely to have sufficient expertise, and there is a lot of dangerous misinformation out there – even among professionals. For example, laypersons and financial/legal professionals alike are generally aware of the “five-year lookback” for asset transfers that will disqualify you from receiving Medicaid, but many believe that you can make gifts of $14,000 per year without a problem. This is not true – that amount is the federal gift tax annual exclusion amount ($15,000 in 2018) and has nothing to do with Medicaid eligibility.

The unforeseen costs of long-term care are the 800-pound gorilla in the room for every estate plan and every farm (or other business) succession plan

Medicaid does not care that the farm has been in your family for five generations. Medicaid does not care that you’ve finally found the perfect young farmer to buy your place after searching for years. Medicaid does not care that you’ve been paying your taxes for decades. If you need long-term care, you, your children, or your buyers may well have to give up assets that you thought were safe.

The good news is that with planning, professionals can help you protect an almost unlimited amount of asset value

The good news is that with planning – preferably four or five years before anyone needs nursing home care – professionals can help you protect an almost unlimited amount of asset value, or ensure that the succession plan you’ve worked so hard on won’t be undone by a Medicaid lien on the farm (which you may have sold several years before). On the other hand, waiting until you need care makes it MUCH less likely that you’ll be able to preserve assets. By the way, we know you don’t plan to go to a nursing home. Do you think anyone in all those nursing homes did?

"Elder Law"

“Elder law” is a code phrase for lawyers who specialize in planning for public benefits like Medicaid and social security disability. Their main trade group is the National Academy of Elder Law Attorneys (NAELA). The NAELA website has an attorney locator here. However, one only need pay the annual dues to be listed there, so you’ll still need to do some investigation to know if you’ve found an experienced elder law attorney. Meet with them first, before you meet with your personal or business attorney, or better yet, bring your personal or business attorney to the meeting with the Elder Law attorney. This is not an area in which to be penny-wise and pound-foolish.

Some questions to ask before deciding whether to have an individual consultation with an Elder Law attorney

It would be reasonable to expect the attorney or her office staff to be able to respond to these questions ahead of time:

– How long have you been practicing Elder Law?

– How many Medicaid applications have you done?

– How many Medicaid appeals (when an application is denied) have you done?

– How many Medicaid irrevocable trusts have you done?

Here are some questions to ask a long-term care insurance salesperson:

– How long have you been selling long-term care insurance?

– How many policies have you sold?

– Do you sell asset-based or “hybrid” policies as well as traditional insurance?

Consulting with both an attorney and an insurance professional

It’s best to consult with both an attorney and an insurance professional. Attorneys tend to make their money by selling trusts and doing Medicaid applications and appeals. Insurance professionals tend to make their money by selling insurance. Don’t be surprised if their prescriptions follow the way they are paid. However, an experienced Elder Law attorney is likely to have a bigger picture of how Medicaid works, especially in the context of an estate or farm transfer plan, and should also have no hesitation about referring you to an insurance professional for additional advice.

A final warning

A final warning: Medicaid is jointly funded by the Federal and State governments, and the background law is Federal – but the States have a great deal of leeway in how they administer the programs, so don’t trust information that comes from professionals in other states. In other words, don’t believe what you read on the internet.

For example, in Vermont in 2017, you can deed your home to your child in a “Lady Bird” or “enhanced life estate” deed in which you reserve the right to live there for your life, and decide at some later date who gets the property upon your death, and the value of your retained rights has no effect on qualifying for Medicaid. In Massachusetts and New Hampshire, however, if you hold a life estate, when you apply for Medicaid, you have to come up with the remaining value of the life estate – basically, what the place would rent for, multiplied by your life expectancy according to special actuarial tables – and pay for that much care before Medicaid will kick in.

Learn more about Donald Sienkiewicz here.

Why Is It Important For Farmers To Have A Long-Term Healthcare Plan?

- The majority of people 65 and over will need long-term healthcare at some point in their lives.

- Depending on the location and level of care needed, average long-term care costs can range from approximately $10,000 to $100,000 per year, or from approximately $800 to $8,300 per month.

- Failing to plan for how to pay for long-term healthcare can result in the loss of a family farm or lack of sufficient care.

- Planning ahead can ensure access to long-term healthcare without losing the family farm, over-burdening family members, or ending up unable to access services like assisted living or a nursing home when needed.

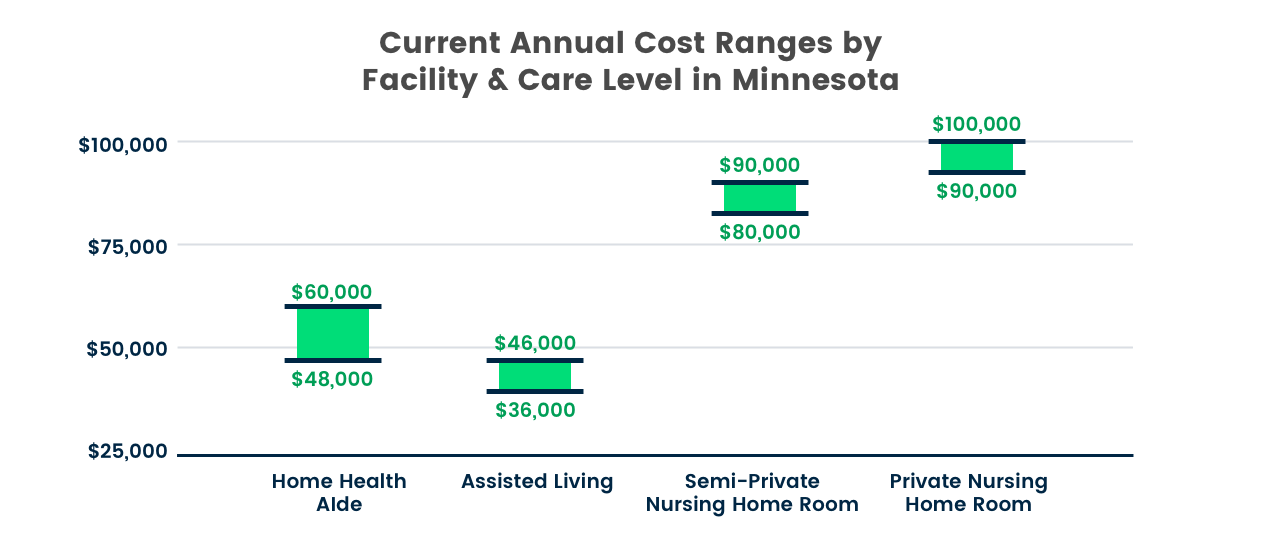

As an example, the chart below shows the range in the cost of care per year in Minnesota. As the chart shows, the cost of long-term care can far exceed most budgets, making the need for a long-term healthcare plan all the more pressing.

Figure 1. Data comes from University of Minnesota Extension, Long-Term Health Care Planning Series, 8/2017, “Estate Planning Principles: Agricultural Business Management," by Gary Hachfeld, David Bau, and Robert Holcomb, Extension Educators.

Costs in the New England states are higher. In 2017, according to the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services, the average annual “private pay” cost for nursing homes that also accept residents whose care is paid for by Medicaid was $117,250.

How Does Long-Term Healthcare Planning Relate to Farm Transfer?

Long-term healthcare planning should always be a consideration in the transfer process for both the junior AND senior farmers – regardless of their age – because of the high likelihood that every person will eventually need care. As the majority of farm transfers occur at the same time senior farmers experience increasing healthcare needs, long-term healthcare concerns should be included in farm transfer plans.

The main benefit of making a long-term care plan at the time of farm transfer is that it can help ensure the costs of care will be covered (without losing the family farm, if that is one of the family’s goals). A farm transfer is such a large financial transaction that it can significantly impact a farmer’s future ability to afford care.

See below to learn how the method of farm transfer can dramatically affect Medicaid coverage (which is a government assistance program for long-term healthcare costs).

How Can Farmers Pay For Long-Term Healthcare?

Among the variety of options available, the best option for each farmer’s situation will depend upon individual care needs and financial capacity. Often, a combination of the methods below is the most effective way to cover the costs of care while working within a person’s financial limitations. You can learn how each method works independently and then see how they can work together to create a workable long-term healthcare plan. Note that this is not a comprehensive list of all possible options; please seek personalized advice from an elder law attorney, financial planner, long-term care insurance specialist, and/or a healthcare professional.

Methods Of Paying For LTHC

Out Of Pocket (Private)

This method is generally not recommended because most people have not saved enough money to afford the cost of care. As shown above, the costs for long-term care are often extremely high and in many cases, planning to cover long-term care costs out of pocket would be unrealistic. Even if paying out of pocket is a realistic option, though, long-term care insurance could be a more effective use of funds. While it is generally not recommended to plan to pay out of pocket, it is necessary in some cases when the patient does not have insurance and/or needs to pay down assets in order to qualify for Medicaid.

Standard Health Insurance (Private)

Most standard health insurance policies do not cover long-term care services. Generally, standard plans are designed to cover short-term, medically necessary skilled care rather than long-term custodial or personal care services (like nursing home or home health aide services). Standard health insurance might cover an initial illness or injury, but if that initial situation leads to long-term care needs, a standard plan likely won’t be of much help. Be sure to carefully study current standard health insurance coverage before purchasing a long-term healthcare insurance policy to ensure there is no gap in coverage.

Long-Term Care Insurance

Long-term care insurance policies are designed specifically to cover the needs of long-term care patients. Generally, these policies pay up to a specified daily amount to policyholders for custodial care services that assist the patient with the daily activities of living. This option may be a more affordable method of covering long-term care costs (when compared to the actual cost of long-term care), but will require monthly premiums to be paid in advance of any potential long-term care needs. The average long-term health care premium cost for couples over 60 is $3,930 per year ($327.50 per month), according to the most recent Long-Term Health Insurance Price Index numbers (2015) from the American Association for Long-Term Care Insurance.

Note that it is best to investigate long-term care insurance sooner rather than later because 1) not all people will be eligible for long-term care insurance; 2) a farmer’s likelihood of qualifying for insurance decreases with age; 3) premiums are often cheaper for younger people and more expensive for older people; and 4) long-term care insurance must generally be purchased in advance of needing care in order to receive coverage. The American Association for Long-Term Care Insurance recommends mid-50s to mid-60s as the ideal age to start looking into long-term care insurance, and provides a helpful primer on long-term care insurance here.

Look for these terms when reviewing and comparing policies:

– Benefit Trigger: The criteria a company will use to determine eligibility for coverage, like the Activities of Daily Living.

– Elimination Period: Generally a time period between 30 and 90 days during which the patient will have to cover the costs of long-term care before coverage under a long-term care policy begins.

– Premium Rate History: Investigating an insurance company’s premium rate history could show if it is likely they will raise the policy premium.

See longtermcare.gov for more tips on purchasing long-term care insurance. For veterans, there are benefits available through the VA Healthcare Program.

Medicare (Government)

Medicare is a federal government insurance program for people over the age of 65 or for people of any age with certain disabilities or end-stage renal disease. Medicare is designed to cover short stays in skilled nursing facilities. It is not designed to cover long-term custodial care. Generally, after a patient is admitted into a Medicare-approved facility, Medicare will cover the costs of skilled care for the first 20 days and any costs beyond $140 for the following 80 days. In most cases, Medicare should not be depended upon to cover the costs of long-term care. It is a common misunderstanding that Medicare pays for long-term care – it does not. The chart below shows the differences between Medicaid and Medicare.

Medicaid (Government)

Medicaid is a federal and state assistance program designed to help those with low income or limited assets cover the costs of medical care, including long-term care services. While the federal government sets requirements for eligibility and available services, the manner in which individual states operate their programs varies considerably. Farmers should check their state’s eligibility requirements (specifically the asset limits and coverage options) to determine if Medicaid will cover their long-term care costs. Each state has a Medicaid assistance office. Medicaid eligibility can be affected by the method of farm transfer farmers choose. Keep reading to find out more.

Combination

Each of the individual methods of paying for long-term healthcare provide access to a range of different levels of care at widely variable costs. For most farmers, using a combination of methods will be the most effective method of covering long-term care needs. Here are some common combinations:

– Long-Term Care Insurance + Standard Health Insurance: This method generally does not require a farmer’s assets be limited or spent down (meaning valuable farmland could more likely be kept in the family, and caregivers could have more financial stability and peace of mind). With both forms of health insurance working together, farmers should be able to access services like a nursing home or in-home care at a cost significantly lower than paying out-of-pocket. However, farmers will have to pay the up-front costs of monthly premiums.

– Long-Term Care Insurance + Medicaid + Medicare: This combination could help those who need care before their assets are low enough to qualify for Medicaid (see below for information on Medicaid asset limits). Should farmers also qualify for Medicare, farmers should receive additional coverage for short-term care.

– Medicaid + Medicare: This method works best for those who already qualify for Medicare and currently have assets low enough to qualify for Medicaid (note that farmland ownership could make qualification for Medicaid difficult or impossible without proper planning). Between the two programs, there should be enough coverage for all long-term care needs.

– Out-of-Pocket + Medicaid + Medicare: Because qualifying asset levels are set so low for Medicaid, if a farmer does not have long-term care insurance, the farmer may have to pay for care costs out-of-pocket until the farmer’s assets are low enough to become eligible for Medicaid coverage. Should the farmer also qualify for Medicare, the farmer will likely not need standard health care insurance.

What Is The Difference Between Medicare And Medicaid?

MEDICARE

Who administers the program?

Medicare is a federal program. It offers the same coverage everywhere in the United States and is run by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, an agency of the federal government.

Where does the money come from?

Medical bills are paid from trust funds that covered patients have paid into during their working life.

Whom does it serve?

- Patients over 65, primarily, whatever their income

- Younger disabled patients

- Dialysis patients

What does it cover?

Skilled medical care, including doctor’s visits and hospital costs up to a limited time period depending on individual circumstances.

What do patients have to pay?

Patients pay part of the costs through deductibles for hospital costs. Small monthly premiums are required for non-hospital coverage.

How can I apply?

The enrollment period begins 3 months before and ends 3 months after a patient’s 65th birthday.

Where can I learn more?

For more information regarding Medicare and its components, go to medicare.gov.

MEDICAID

Who administers the program?

Medicaid is a federal-state program. Coverage and eligibility rules vary from state to state. The program is run by state and local governments within federal guidelines.

Where does the money come from?

Medicaid is a welfare program jointly funded by the federal government and states.

Whom does it serve?

- Low-income patients of any age

- Patients with limited assets

What does it cover?

● Skilled medical care, including doctor’s visits and hospital costs

● Long-term care services in nursing homes or at home, including custodial care

What do patients have to pay?

Patients usually pay no part of costs for covered medical expenses. A small co-payment is sometimes required.

How can I apply?

To see if you qualify, check

healthcare.gov/medicaid-chip/eligibility/

Where can I learn more?

For more information on Medicaid, go to medicaid.gov.

How Can Farm Transfer Impact Medicaid Eligibility?

Medicaid is the one method of covering long-term care costs that is most likely to be affected by the manner in which the farm is transferred. Farm transfer affects Medicaid because eligibility is determined by available income and assets.

In order to be eligible for Medicaid, an applicant may only have a certain amount of “countable” income and assets. “Countable” assets typically include checking and savings accounts, stocks and bonds, property other than a primary residence (like a cabin or farm equipment), and vehicles beyond one primary vehicle, among other items. Generally, “countable” assets do not include an applicant’s primary residence, some personal property and belongings, and a primary vehicle, although the rules vary from state to state.

For example, in Minnesota, an individual must have under $3,000 in countable assets to be eligible for Medicaid assistance. Similarly, in California, the asset limit for a single person is $2,000. The limit is also $2,000 in North Carolina and Texas.

Because Medicaid asset limits are set so low, many people who could not otherwise afford the costs of long-term care need to “spend down” their assets in order to become eligible. Senior farmers can spend down their countable assets through a farm transfer, but only through careful planning. In fact, some methods of farm transfer may render a senior farmer ineligible for Medicaid assistance even though the farmer may possess no liquid assets.

For example:

In a farm transfer that occurs through a contract for deed, the junior farmer makes monthly payments to the senior farmer over a number of years. Those payments go towards the purchase price of the farm. The key to this arrangement is that the senior farmer retains ownership (the deed) to the farm until the final payment is made, at which time farm ownership (the deed) should be transferred to the junior farmer. Depending on the terms of the contract, it could be 10, 20, 30 or more years before ownership of the farm is transferred. In the meantime, the farm would be considered a “countable” asset for the senior farmer for purposes of Medicaid eligibility. In a case such as this, should the senior farmer seek to qualify for Medicaid coverage before the ownership of the farm actually transfer, it is likely that he/she would not qualify for Medicaid.

However, with careful (and early) planning, farmers can successfully transfer a farm and qualify for Medicaid. The key is determining the state Medicaid rules as early as possible, determining farm transfer goals, and figuring out how to achieve farm transfer goals while still qualifying for Medicaid (if necessary). The best way to start this process is to consult with an elder law attorney and/or an estate planning attorney who has experience working with farmers.

What Is The Look-Back Period?

When determining a Medicaid applicant’s assets, most states have a “look-back period.” This means that states are allowed to review any asset transfers made before the applicant filed for Medicaid up to a certain length of time (typically a number of months or years). If the applicant made a gift or other significant asset transfer within the “look-back period” for which the applicant did not receive full compensation, the state will be able to apply that “lost value” to an applicant’s asset assessment. This rule is in place to keep Medicaid applicants from transferring assets shortly before applying in order to qualify for assistance. While the length of the “look-back period” varies from state to state, the federal maximum length for the “look-back period” is currently 60 months (or 5 years).

The purpose of the “look-back period” is to ensure that applicants for Medicaid are truly in need of assistance and not manipulating their assets in order to qualify for government benefits. If an asset is transferred within the look-back period in a manner that does not capture the full value of the asset, the state will not provide benefits until the missing value is recaptured.

The following example demonstrates how this works:

A land trust has offered to buy the development rights to a farmer’s land in the form of a conservation easement. The value of those development rights is $150,000, but the land trust can only pay $100,000. Wanting to conserve the land and glad to accept $100,000 rather than nothing, the farmer accepts the deal and puts the easement on the land. However, by selling the conservation easement for $50,000 less than full value, under the law the farmer is considered to have donated $50,000 to the land trust.

The next year, the farmer suffers a bad fall and finds himself in need of care as he can no longer wash, dress, toilet, or feed himself. The cost of the care he needs each month is $5,000, which he cannot afford, so he applies for Medicaid. Although his current assets are below the allowable asset level, his $50,000 “donation” to the land trust was within the 5-year look-back period. As a result, he will not be covered by Medicaid until that amount, $50,000, would be used to cover his medical costs. At $5,000 per month, it will be 10 months before he is eligible for Medicaid coverage. For that period of time (10 months), he will have to pay for his medical costs out-of-pocket or through an insurance program. Of course, the farmer doesn’t actually have that $50,000 to pay for medical costs, so he and his family will have to figure out how to pay or how to arrange for family or other caregiving.

The Future Of The Look-Back Period

Note that it is possible that the federal and state look-back periods may be expanded or made limitless. As a result, more (and perhaps all) transfers that appear to have been for the purpose of qualifying for Medicaid may be counted towards an applicant’s asset assessment. Accordingly, those planning on utilizing Medicaid to cover long-term healthcare costs should carefully consider the method by which they transfer their farm and when to transfer or gift assets.

How An Attorney Can Help

How An Attorney Can Help

The Attorney’s Role

It’s not an attorney’s job to make decisions for farmers or to set farm transfer goals. Instead, attorneys can provide information about pros and cons of different options, advice about what is common versus unusual, fair versus unfair, etc. Attorneys can help farmers understand the universe of possible farm transfer goals and help narrow down individual options so that farmers can make final decisions.

How An Attorney Can Help With Long-Term Health Care Planning

- For assistance regarding Medicaid eligibility, consult with an elder law attorney, preferably with experience in farm succession/farm transfers or estate planning.

- For assistance regarding Medicare eligibility, consult with an elder law attorney, preferably with experience in farm succession/farm transfers or estate planning.

- Additionally, it may be advisable to consult a financial planner to ensure that your long-term care plan and farm transfer plan meet your financial needs and goals.

- Attorneys can help make sure your long-term health care plan fits together with your other farm transfer goals.

Related Legal Tools

The Center for Agriculture and Food Systems is an initiative of Vermont Law School, and this toolkit provides general legal information for educational purposes only. It is not meant to substitute, and should not be relied upon, for legal advice. Each farmer’s circumstances are unique, state laws vary, and the information contained herein is specific to the time of publication. Accordingly, for legal advice, please consult an attorney licensed in your state.

Additional Resources

Additional Resources