OPAVs

- What Is an OPAV?

- Tools for Revenue, Affordability, and Legacy

- Sale, Donation, and Bargain Sale

- Land Trust or Government Agency

- How OPAVs Work

- The OPAV Deed

- Impact on Future Landowners

- Impact on the Value of Land

- What About a Mortgage?

- Pros and Cons of OPAVs

- How an Attorney Can Help

- Additional Resources

What Is an OPAV?

What Is an OPAV?

An OPAV (Option to Purchase at Agricultural Value) is a voluntary legal agreement that restricts the sale of land to only certain farmers or to family members, and restricts the sale price to agricultural value (versus the higher fair market value). An OPAV is placed when the landowner sells or donates an OPAV to a land trust or government agency. Once land has an OPAV, its value is usually lowered (because the land no longer able to be sold to all willing buyers and must be sold for agricultural value). This decreased value can make land with an OPAV more affordable for buyers, including farmers who may want to purchase the land.

Farmer Spotlight:

Say Hay Farm

Chris Hay runs an organic mixed vegetable and poultry farm that supports CSAs in the Sacramento Valley and San Francisco Bay Area and sells to farmers markets, independent grocers, and restaurants.

Tools for Revenue, Affordability, and Legacy

Tools for Revenue, Affordability, and Legacy

OPAVs are one of several legal tools that help farmers balance goals of: 1) generating revenue for farming or retirement; 2) making their land more affordable to future farmers; 3) keeping their farmland in farming; and 4) maintaining a treasured legacy of sustainable farm stewardship.

Other legal tools include:

- Affirmative agricultural easements (requiring land to be farmed),

- Conservation easements (prohibiting certain types of development),

- Differential assessment/current use programs (lowering taxes on agricultural land), and

- Federal farm programs (loans, grants, cost-shares).

These tools can be used separately or in combination, and are discussed within the Access Tools section and elsewhere in this toolkit.

Frequently, OPAVs are used with or can even be part of a conservation easement. For properties that already have a conservation easement, an OPAV can be added later. No matter the timing, a landowner of a property with both a conservation easement and an OPAV must abide by all restrictions of each. In these cases, OPAVs provide an extra layer of farmland preservation protection by explicitly stipulating that the land must be kept in agricultural use or sold to a working farmer.

Sale, Donation, and Bargain Sale

In the case of selling an OPAV, the landowner would receive a cash payment. This is just like selling a house in that there’s a purchase price, which the buyer pays to the seller. In the case of donating an OPAV, the landowner does not receive any cash, but may receive important tax benefits.

Sometimes, selling an OPAV at its full value is a bit too expensive for a buyer. Other times, an OPAV seller may need both the cash and the donation-linked tax benefit. In those cases, an OPAV can be sold as a “bargain sale.” This means the landowner gets less cash than if it were a full value sale, and a lower tax benefit than if it were a full donation. Still, the landowner gets some cash and some tax benefit. When this bargain sale occurs, the landowner may qualify for federal and/or state tax benefits for the portion of the land value “donated” (equal to the difference between the value of the OPAV and the lower sale price).

For example, if the value of an OPAV were $50,000, a bargain sale might involve 1) a cash payout to the landowner of $25,000 and 2) the landowner donating the other $25,000 and getting tax benefits for that donated portion.

Land Trust or Government Agency

To sell or donate an OPAV, farmers need to find an organization willing to own the OPAV. Owning an OPAV is usually referred to as “holding” it and the owner is usually called the “holder.” Usually, an OPAV holder is a land trust or a government agency.

Funding to acquire OPAVs is limited. As a result, many sales are bargain sales, which stretches a holder’s limited dollars further. The holder of the OPAV is responsible for monitoring and enforcing the terms of the OPAV, which, in general, is in perpetuity or forever. Consequently, the organization agreeing to hold the OPAV needs to have the capacity to monitor the land with the OPAV and enforce the terms of the OPAV going forward.

So, while OPAVs, affirmative agricultural easements, and conservation easements are powerful tools, they are available only if there is an organization with money, capacity, and interest in acquiring and holding the easement.

Another consideration is finding the right fit for the organization that will hold the OPAV. For example, a land trust dedicated to preserving wildlife may not be willing to hold an OPAV. Finding an agriculture-oriented organization is crucial for farmers considering placing an OPAV on their land.

Once an OPAV is in place, the holder will check in periodically to make sure that the terms of the OPAV are being followed. This is called “stewardship.” When a property is sold, the OPAV holder will usually introduce themselves to the new owner and make sure the new owner is up to speed regarding the OPAV agreement. The OPAV holder and the landowner will have an ongoing relationship and must work together in many ways.

How OPAVs Work

How OPAVs Work

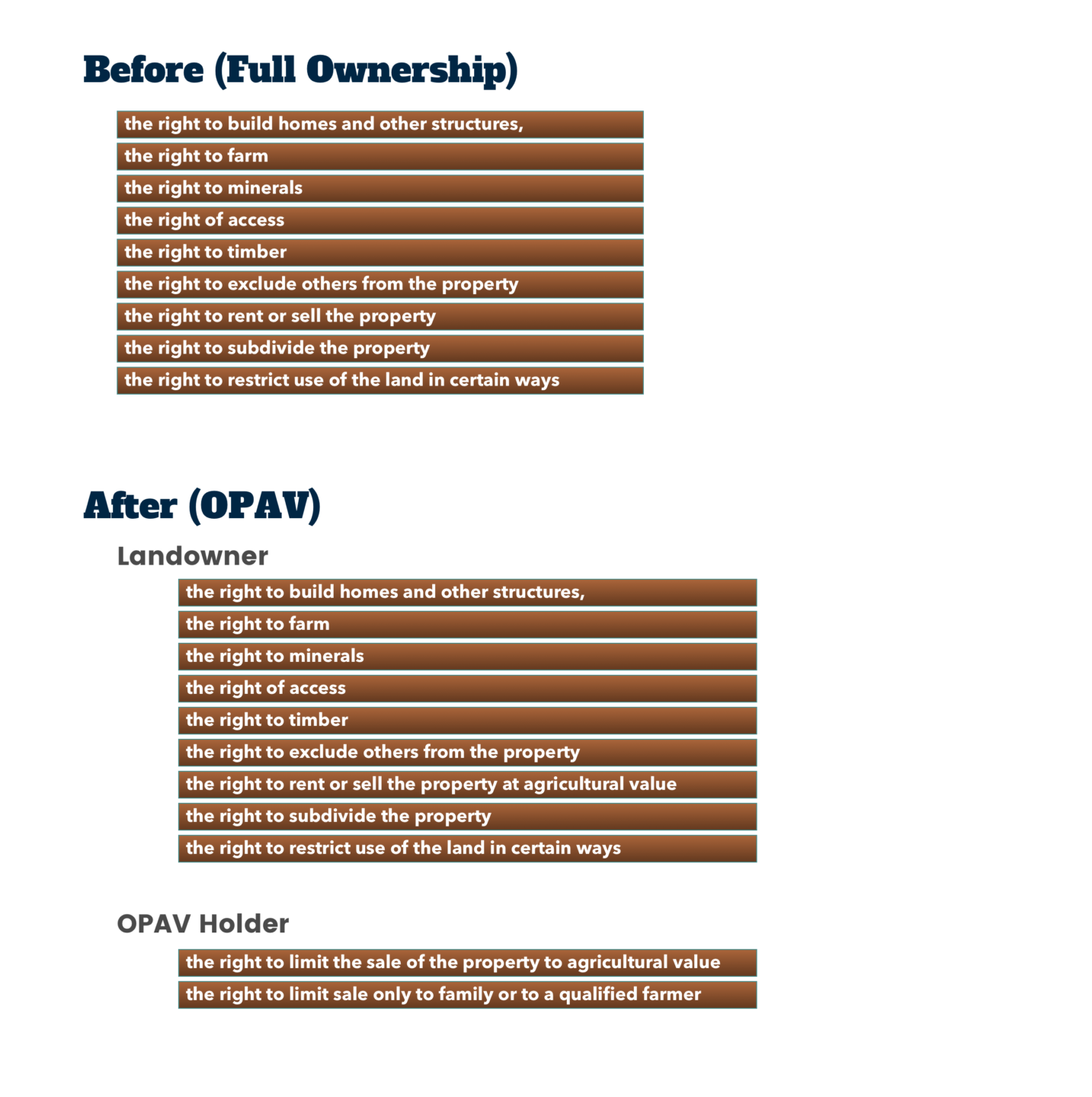

Full ownership of land comes with a variety of ownership rights. Some of these rights include:

- the right to build homes and other structures,

- the right to minerals,

- the right of access,

- the right to timber,

- the right to exclude others from the property,

- the right to rent or sell the property,

- the right to subdivide the property, and

- the right to restrict use of the land in certain ways.

These property rights can be thought of as a “bundle of sticks.” A landowner can hold all the sticks in the bundle or transfer some of those sticks to others. An OPAV takes several of the sticks in the bundle and transfers them to the buyer. After the OPAV is in place, the landowner still has many of the sticks, such as the right to farm, and the OPAV holder has other sticks, such as the right to limit commercial development and ensure the land is kept in farming.

The “bundles of sticks” concept is commonly used to illustrate the separation of property rights between the landowner and an OPAV or easement holder. Nevertheless, it’s important to note that it is an oversimplification. As discussed below, the OPAV document itself is long and complicated, and goes into great detail about how the land can and cannot be used.

The OPAV Deed

Because OPAVs limit a landowner’s use of a property, and give an OPAV holder certain rights, it is very important to specifically describe who can do what and under what circumstances. And because an OPAV is a property right, it is transferred from the landowner to the OPAV holder through a written deed, typically called an Option to Purchase at Agricultural Value, that is then recorded publicly within the land records.

OPAV deeds are a very big deal. They can be very long and can take months, or even a couple of years, to negotiate. Frequently, the landowner and the OPAV holder go back and forth many times giving each other revised drafts. Usually, a lawyer will be involved on behalf of the landowner and another lawyer involved on behalf of the OPAV holder.

Impact on Future Landowners

Once everyone has signed the OPAV, and it has been recorded within the land records, it is binding on all current and future landowners, including anyone who may use the land. As lawyers say, OPAVs “run with the land” – meaning they become a part of the chain of title and stay in effect even after ownership of the land changes. A new farmer buying land with an OPAV is bound by the OPAV. The new farmer is not allowed to negotiate new terms with the OPAV holder. So, a farmer buying land with an OPAV should closely examine the OPAV deed to make sure they understand its limits and will be able to comply with them without undue economic harm.

While being required to transfer to a family member or qualified farmer can help keep land both affordable and in agricultural use, it can also make for a lengthy transfer process. Before a farm-seeker is able to acquire land restricted by an OPAV, they must determine whether they meet the OPAV criteria, i.e., whether they are considered a qualified farmer or family member. A farm-seeker should work with the current landowner and OPAV holder to figure this out. The OPAV should thoroughly define the requirements. If there is any confusion, the landowner or farmer should review the document with the OPAV holder. If the farm-seeker does not meet the definition of a qualified farmer or family member, it is possible for the OPAV holder to waive its option. However, the farm-seeker must gain such approval from the holder.

This collaboration among landowner, farm-seeker, and OPAV holder typically has two major phases. First, an informal phase takes place where the concepts are explored and preliminary, non-binding, next steps are mapped out. Second, the process moves to the formal stage, typically involving legal counsel and/or other professionals, to undertake the required steps according to the terms of the OPAV.

Once a farm transfer has successfully occurred, the new landowner is required to follow the terms of the OPAV and any other agreements in place.

Impact on the Value of Land

When done correctly, selling an OPAV is a great way to all but guarantee that your land stays in agricultural use and is affordable for farmers, while still ensuring that the landowner eventually receives as much value as possible for the land during sale.

Generally, a property’s value is based on its “highest and best use,” which is typically residential or commercial development. However, by ensuring land is either sold to family or farmers, OPAVs limit a landowner’s right to sell for development. If a landowner attempts to sell land for development, the OPAV holder has the option to purchase the land at its agricultural value instead. The agricultural value is the price that a farmer would pay for the land to use it for agriculture. Because the agricultural value of a property is often far lower than the market value for development, an OPAV lowers the value of the land and makes the property more affordable to farm-seekers.

There is no established rule of thumb for the value of OPAVs. In some cases, OPAVs can sell for up to 70 percent of a property’s fair market value. But, if development pressure in an area is so low that the fair market value is the agricultural value, an OPAV may not be very useful outside of ensuring farmer-to-farmer sales.

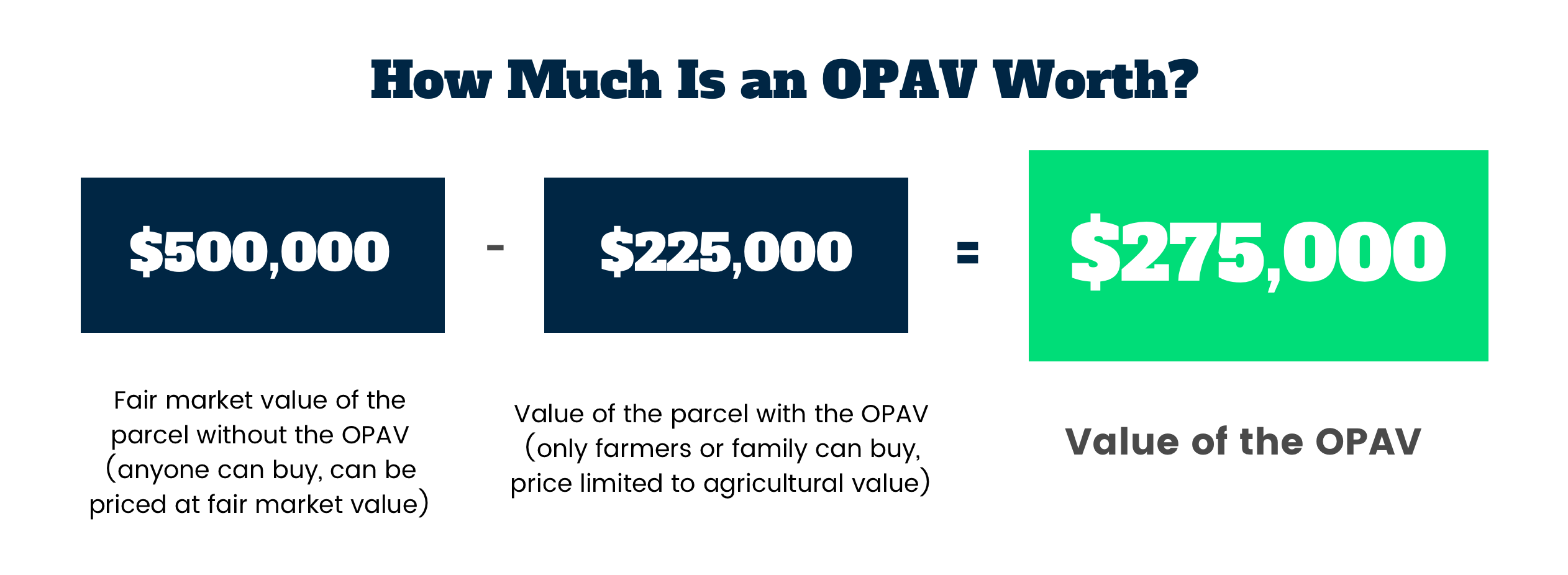

The value of an OPAV can vary widely depending on various circumstances, including the surrounding land use, the economic means of local farmers, and the desirability of the land for farming. It could be a very small percentage of the fair market value or a very large percentage of the fair market value. The value of an OPAV is determined by a qualified appraiser. The appraiser determines the value of the land before the OPAV and subtracts the value of the land after the OPAV to determine at the value of the OPAV. For example,

When selling an OPAV, landowners are essentially receiving a portion of the fair market value of their land, either through payment for the OPAV by the OPAV holder (a land trust or government agency) or through tax benefits from the donation of the OPAV.

Because an OPAV generally lowers the property’s fair market value, farm-seekers should be able to purchase conserved land at a lower price. Or, farm-seekers looking to buy land without an OPAV may have a unique opportunity to purchase the land and simultaneously grant an OPAV. If a farm-seeker is unable to afford farmland or is interested in lowering the purchase price, the farm-seeker could look for an organization such as a land trust willing to buy an OPAV on the property at the same time the farmer purchases the land. This way the OPAV holder pays for the value of the OPAV and the new farmer pays for the lower value of the land with the OPAV in effect. It is important to note that OPAV transactions are not commonplace because they require the right circumstances—availability of land, seller, buyer, funding, and an OPAV holder, as well as closely coordinated land transactions.

Farm-seekers considering buying conserved land (or buying land and restricting it with an OPAV) should also consider that if they later choose to sell the land, they will generally receive the reduced value of the land. However, sometimes land continues to appreciate (increase in value) even with OPAV restrictions. Farmers considering placing an OPAV on their land might also want to consider granting the OPAV holder a conservation easement or an affirmative agricultural easement.

What About a Mortgage?

If a farm has a mortgage (as many do), it is still possible to place an OPAV. It does, however, add some extra steps. Typically, both an OPAV holder and a mortgage company will want to be in first position, meaning they will be paid first in the event of a foreclosure or other default or loss. It is possible that a mortgage company would not allow an OPAV. This is especially likely if the proceeds from the sale of an OPAV would not be enough to completely pay off the mortgage. If there is a mortgage, contact your bank or mortgage company to discuss. Sometimes, someone from the land trust or the government agency who would hold the OPAV can assist in this conversation. And if you have a lawyer, your lawyer can assist you.

Pros and Cons of OPAVs

Pros and Cons of OPAVs

Benefits of OPAVs

Benefits of OPAVs

- Selling an OPAV can be a good way to get some cash out of the property.

- Landowners who donate OPAVs may receive tax benefits.

- OPAVs can reduce the property’s overall value, making the land more affordable for future farmers.

- OPAVs can provide peace of mind that a property will remain in agricultural production or in the family.

- Landowners can negotiate, creating an agreement tailored to their needs.

- Buying land restricted by an OPAV may create tax benefits.

Drawbacks of OPAVs

Drawbacks of OPAVs

- Limited number of OPAV buyers.

- Limited amount of funds available to purchase OPAVs.

- Most OPAVs are permanent and bind all future landowners (including heirs).

- Potential OPAV holders and farmers may not always share a common vision.

- OPAVs can reduce the property’s overall value and limit the pool of buyers, making the land worth less for future sales.

- Farmers with a mortgage may have limited options with respect to OPAVs.

- The amount of a loan offered by a bank to mortgage a property with an OPAV on it may be reduced.

- New owners are not allowed to negotiate new terms with the OPAV holder.

- Selling land after it has an OPAV can make the sale slower and more complicated.

- OPAVs may not ensure affordability for new and beginning farmers, who typically cannot compete against well-established farmers.

How an Attorney Can Help

How an Attorney Can Help

The Attorney’s Role

It’s not an attorney’s job to make decisions for farmers or to set farm transfer goals. Instead, attorneys can provide information about pros and cons of different options, advice about what is common versus unusual, fair versus unfair, etc. Attorneys can help farmers understand the range of possible farm transfer goals and help narrow down individual options so that farmers can make final decisions.

How An Attorney Can Help With OPAVs

- Negotiate the terms of the OPAV with a land trust or government agency.

- Help decide which parts of the farm to put into the OPAV and which to exclude.

- Analyze the terms of the OPAV to help farm-seekers assess what they mean and how they may affect or restrict a new farm operation.

- Negotiate with a bank (mortgage holder) to facilitate a sale or donation of an OPAV.

- Determine a strategy for combining an OPAV with other transfer or conservation tools.

- Help farmers understand the possible tax implications of selling or donating an OPAV.

Related Legal Tools

Additional Resources

Additional Resources

National Young Farmers Coalition, Farmland Conservation 2.0: How Land Trusts Can Protect America’s Working Farms (explains how farmers can use conservation easements, OPAVs, OPAVs and more to make farmland more affordable)

Land Trust Alliance, Find a Land Trust (tool to find a land trust near you)

The Center for Agriculture and Food Systems is an initiative of Vermont Law School, and this toolkit provides general legal information for educational purposes only. It is not meant to substitute, and should not be relied upon, for legal advice. Each farmer’s circumstances are unique, state laws vary, and the information contained herein is specific to the time of publication. Accordingly, for legal advice, please consult an attorney licensed in your state.