Trusts

Overview

Overview

Trusts can help farmers manage and distribute their assets in order to meet farm transfer goals – both during life and after death. Trusts that can be used during a farmer’s life are called “living” trusts, and trusts that are effective only at death are called “testamentary” trusts. Trusts can be used as the primary tool in a farm transfer process, and one or more types of trusts can be used simultaneously by the same farmer. There are three main types of trusts particularly relevant to farm transfer: 1) Revocable Living Trusts; 2) Irrevocable Living Trusts (of which one sub-type is a Charitable Remainder Trust); and 3) Testamentary Trusts. The basic characteristics and the pros and cons of each type are discussed more fully below.

Trusts are often used together with a will as part of an estate planning strategy, and can be used to provide for an uninterrupted transition of the farmland and farm business. To ensure farm transfer goals are met, trusts should generally be used in combination with at least the following: a will, long-term health care planning, life insurance, and tax planning for both estate taxes and gift taxes.1 Note that certain trust arrangements may impact a farmer’s Medicaid eligibility.

Creating an effective farm transfer plan that actually does what you want it to do will almost always require the help of an estate planning attorney. Estate planning attorneys can create trusts, draft wills, help keep farmland in the family, help find tax advantages, and determine the best combination of tools to meet farm transfer goals. It’s best to find an estate planning attorney who has experience working with farmers and understands the special rules and benefits that apply to farms under state and federal laws.

Farmer Spotlight:

Sunbow Farm LLC

Harry MacCormack has owned 15 acres of farmland on the edge of Corvallis, Oregon, since 1972. Harry’s two adult children live off the farm and are not interested in farming, which led Harry to consider innovative possibilities for passing his land on to the next generation. Read more about Sunbow Farm here.

What Are Trusts?

What Are Trusts?

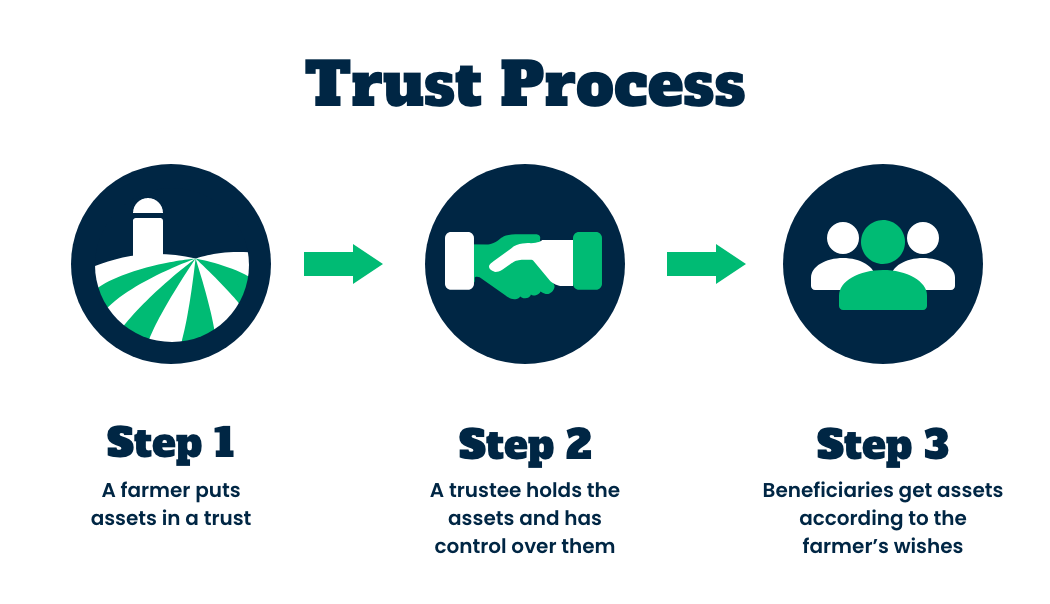

A trust is a way to hold, manage, and distribute property. A trust could be described as a custom-designed bucket that holds and takes care of your assets during life and distributes them after death. Trusts can be used as the primary element of an estate planning strategy, and have four basic elements:

1. Trust property (like farmland, a farm business, or cash)

Trusts can hold any type of property, but that property must be formally transferred to the trust. If an asset has a title (like land or equipment,) the title must be formally amended to reflect ownership by the trust. Placing property within the trust is called “funding the trust,” and must be done correctly by following legal guidelines and preparing appropriate documentation. If title of an asset is not properly transferred to the trust, the trust will not hold (or “own”) the property and therefore, the terms of the trust do not control/govern the management, administration, and/or distribution of that asset.

2. A trustee (like a farmer or a trusted representative)

A trustee is an individual who has a fiduciary duty to oversee, manage, administer, and protect the assets held in a trust for the benefit of the beneficiaries of the trust. Depending on the type of trust, a trustee can also be the owner of the trust property, meaning farmers can place their own property in a trust and then name themselves as the trustee. It is advisable to name a successor trustee who can take over management of the trust in case the trustee farmer can no longer take care of trust matters, due to incapacity, incompetency, disability, and/or death. Alternatively, a farmer can name a third party to immediately serve as the trustee, and this trustee can be a trusted friend or advisor. A trustee can also be an institution, like a land trust or a bank trust department.

3. Beneficiaries (like children, business partners, or others)

The beneficiaries of a trust can be a farmer’s spouse, children, grandchildren, or the farmer herself. Trust beneficiaries can also be non-family members or institutions (like a farm advocacy nonprofit or a land trust).

4. Instructions and guidelines for how the trust property should be used and/or distributed

Just like wills, trusts can be used to distribute property. However, trusts allow for more flexibility than wills because some types of trusts can be used to manage and distribute assets during a farmer’s lifetime. Trusts can also be used to distribute property in installments, rather than all at once, and can impose other requirements for the beneficiaries. Additionally, because the trust holds the property, rather than the farmer, upon the farmer’s death probate is not necessary to transfer title or ownership of the farmland or farm business.2

In summary, while there are several different types of trusts, they all follow a typical structure: An individual (a farmer) distributes or manages property for the benefit of one or more people or organizations (perhaps her children) by placing the property in a trust managed by a trustee (either the farmer herself or a third person). The trustee must manage the property in the trust for the benefit of the beneficiaries.3

What Is Estate Planning?

Estate planning (also referred to in the farm transfer context as “succession planning”) is the process of strategically controlling your assets during your life and strategically distributing your assets at death. Important estate planning goals are: 1) Ensuring you have the necessary income and resources upon which to live; 2) Ensuring that upon your death, your assets go to the people and/or organizations you intend; and 3) Minimizing estate taxes, fees, delay, disputes, confusion, and any associated court costs.

Estate planning involves setting farm transfer goals and using legal tools and strategic planning to meet those goals. One or more trusts can be used as a primary estate planning vehicle, along with a will. Your trust(s) and/or will should be tailored to meet your farm transfer goals. Property, farm business ownership, and the transition or distribution of such assets should be examined and tailored to your farm transfer goals. Estate liquidity issues should be reviewed and can sometimes be addressed with the help of life insurance. Family income requirements should be matched with projected income. Other issues to be considered include treatment of heirs (farming and non-farming), incapacity planning through the use of powers-of-attorney and health care directives, disability planning, tax planning, personal representative or trustee selection, estate administration cost savings, long-term health care issues, and more, depending on your personal situation.

Estate planning can be a simple or complex process depending upon the size and composition of your estate, your family situation, and your business situation. No two families have precisely the same set of circumstances. Farm families, however, tend to have more complex estates and goals. Effective estate planning for farmers requires the help of an estate planning attorney, preferably one that has experience working with farmers. Without legal help, specific farm transfer goals are unlikely to be met. Investing in strategic estate planning up front is often far less costly and disruptive to a farm family than handling these issues after a disability or death.

How Do Trusts Work?

How Do Trusts Work?

Trust Creation

Although state law varies, there are three basic legal requirements for creating an effective trust.4

Intent. The settlor (trust-creator) must intend to create a trust.

Beneficiaries. A trust must have ascertainable individuals to ultimately direct assets to (for example, a farmer’s spouse or children). Beneficiaries do not need to be directly identified, but must be identifiable. This means a farmer could place property in trust for her “grandchildren,” both born and unborn. In this situation, the unborn grandchildren cannot be directly identified by name (as they do not yet exist) but are still “identifiable.” Furthermore, a settlor can name him or herself as the beneficiary of his or her own trust.

Trust Property. Property (cash, land, equipment, or other property) must be transferred into a trust either during the settlor’s (trust-creator’s) life or by a will upon his death. This is referred to as “funding a trust.”5 Funding a trust must be done with the appropriate formal paperwork. If the formalities are not done correctly, the trust is “nothing more than a pile of paper.”6 An estate planning attorney can help with the formalities so that your family can rely on a trust to function properly during your life and after death. Hiring an attorney to help assist in drafting a trust document is important to ensuring that the trust is valid and that it manages and distributes a farmer’s property according to the farmer’s wishes.

Trust Operation

Once a valid trust is established, the trustee has a fiduciary duty to ensure that the settlor’s (farmer’s) assets are administered according to her wishes and that the trust assets are managed in the beneficiaries’ best interests.7 For some types of trusts, like a Revocable Living Trust, the farmer can be the trustee and manage the assets during her own life. Trust operation varies widely based on the type of trust selected.

Why Use A Trust?

Trust Types

A trust arrangement can take many different forms, but trusts typically fall within one of two general categories: 1) living trusts (effective during life and at death); or 2) testamentary trusts (effective at death only).

A living trust (also known as an inter vivos trust) is a trust which can go into effect during the farmer’s (settlor’s or grantor’s) life to manage and/or distribute assets, but can also be used to distribute a farmer’s assets at death. Living trusts are often set up to avoid probate costs at death, since living trust assets do not need to go through the court-administered probate process. Avoiding probate means that a farmer’s living trust assets do not become public and can generally be transferred more quickly and smoothly at death, helping to provide for an uninterrupted farm business transfer. Living trusts can also be useful in providing management and/or transfer of control through a trustee for elderly, ill, or disabled family members.8

Within the category of living trusts, there are two main types of trusts that are particularly relevant to farm transfer. They are called Revocable Living Trusts (RLTs) and Irrevocable Living Trusts (ILTs). As their names suggest, the difference between these trusts is that one type is “revocable,” meaning it can be changed, and the other type is “irrevocable,” meaning it can not be changed.

Summary of Trust Types:

Revocable Living Trust (RLT): Can be used during life and at death of the farmer; allows management of the farm in case of disability or incapacity; can allow opportunity for farming heir to buy into the business; flexible and can be amended in certain circumstances before the farmer’s death; avoids probate for assets placed in the trust; the value of the assets in RLT remain in the value of the farmer’s estate for estate tax purposes.

Irrevocable Living Trust (ILT): Can be used during life; cannot be changed; assets cannot be reclaimed; includes Charitable Remainder Trusts; does not protect assets from Medicaid spend down unless the 60 month lookback period is over; the value of assets in ILT are no longer included within the value of the farmer’s estate for estate tax purposes.

Testamentary Trust: Become effective at the farmer’s death; most often created by a will (but can be created under a RLT or ILT); used to minimize estate taxes and protect assets; does not avoid probate if created under a will; can also be called A-B Trusts, By-Pass Trusts, Credit Shelter Trusts, or other names.

Revocable Living Trusts, Irrevocable Living Trusts (of which one type is a Charitable Remainder Trust), and Testamentary Trusts are described in detail below.

Revocable Living Trusts

Revocable Living Trusts

For farmers, Revocable Living Trusts (RLTs) can be useful as a primary tool for farm transfer – as long as farmers can put in the time, effort, and investment in legal help to properly set up and manage a RLT.

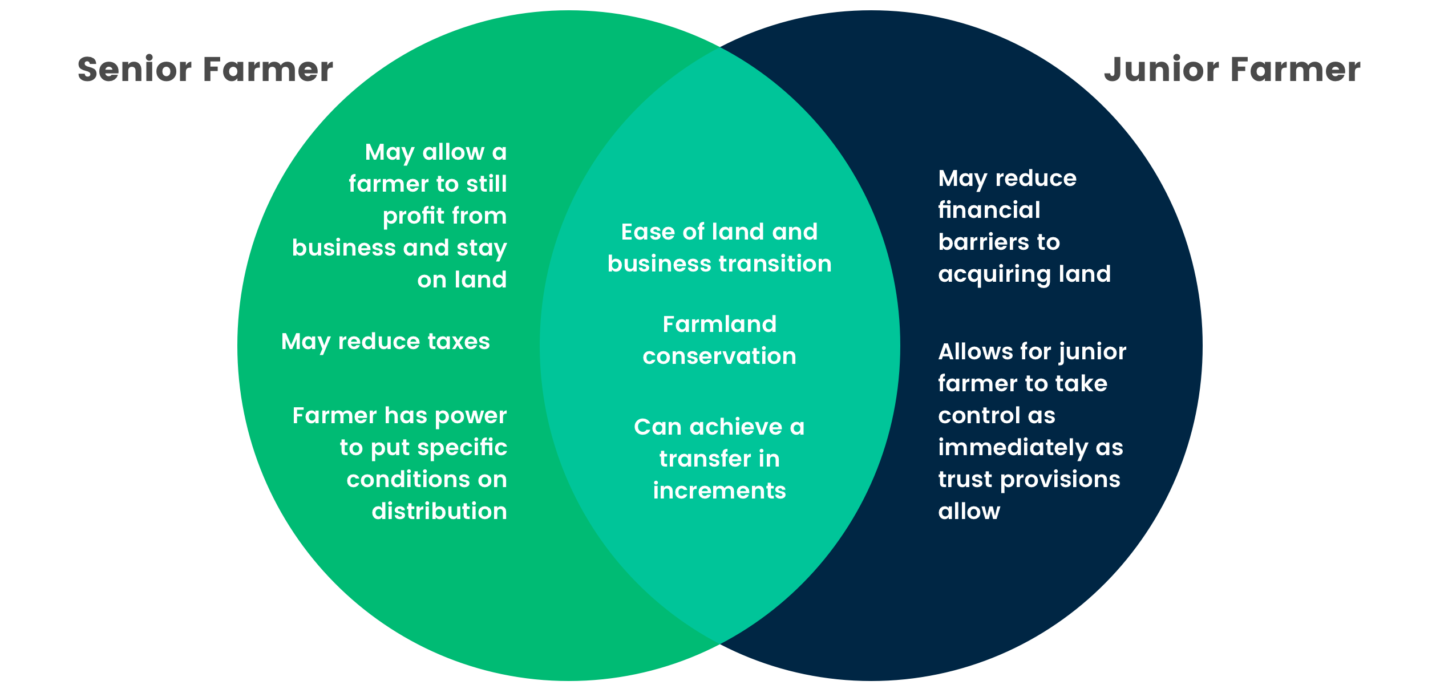

Farmers who use RLTs place their property into the trust “bucket” by formally transferring title of their property into the RLT. This is called “funding the trust,” and must be done formally with appropriate paperwork. Then, farmers name themselves as both the trustee of the RLT and the beneficiary of the RLT.9 That means the farmer still owns the assets, but owns them via the trust instead of directly as an individual. While the assets are within the RLT, they can be managed and transferred by the farmer (or by a successor trustee appointed to manage the trust upon the farmer’s disability, incapacity, or death). RLTs can provide a vehicle to allow a farming heir who does not have sufficient capital to purchase a farm business outright to gradually buy into the family farm business, as purchase agreements and buyout provisions can be written into the RLT and payments can be spread out over time.

RLTs have an advantage over a will as a primary farm transfer tool because while a will automatically triggers the probate process, an RLT bypasses the probate process. Keep in mind, though, that even farmers with RLTs generally need a will that accompanies the RLT and functions to transfer any assets into the trust that may have remained outside of the RLT for any reason. This type of will is often called a “pour-over” will.10

Advantages Of An RLT

Advantages Of An RLT

- Avoids Probate. RLTs can serve as the primary estate planning tool, thus avoiding the probate process for all property within the RLT. This saves on expense, delay, and publicity at death.

- More Control Over Distribution. Farmers can include trust provisions which instruct a trustee when and how to distribute assets from the trust to the beneficiaries, both during life and at death. For example, if a beneficiary is a minor, a settlor can instruct the trustee to withhold payments until the beneficiary is eighteen, or older. Farmers can also include provisions in a trust to allow a junior farmer to progressively buy into the business by incorporating purchase agreements and other provisions into a trust document.11

Disadvantages Of An RLT

Disadvantages Of An RLT

- Initial and Ongoing Expenses. In comparison to a will, creating a trust document may require more time and money to prepare depending on the complexity of a farmer’s situation and goals. Additionally, management of an RLT requires time and potentially some expense.

- No Creditor Protection. Unlike with a testamentary trust, creditors can reach assets within RLTs.12

- Medicare & Medicaid Eligibility. Since a farmer still retains the right to use and benefit from assets in a RLT, farmers may be ineligible for government health benefits.13 In about half of states, known as “income-cap states,” it may be possible to work around this issue by setting up a qualified income trust (also known as a Miller Trust).14

Irrevocable Living Trusts (ILTs)

Irrevocable Living Trusts (ILTs)

For farmers, Irrevocable Living Trusts (ILTs) are generally used to reduce the size of the farm estate in order to reduce taxes and/or to establish a trust for beneficiaries (either family beneficiaries or charitable beneficiaries). An ILT removes property from a farmer’s estate forever, and the farmer cannot get it back.

An ILT removes property from a farmer’s estate forever, and the farmer cannot get it back.

Placing assets into an ILT is final; farmers no longer own the assets, and farmers retain no decision-making power over the assets.15 Additionally, creating an ILT may require the preparation and filing of additional tax returns upon the creation of the ILT and throughout the administration of the ILT.

ILTs are generally not used as a primary farm transfer tool because retiring farmers generally still need property and the related income to live on during their lifetimes. However, if farmers can retain enough property and associated income to live on, and can afford to permanently give up ownership of a farm business, farmers could use an ILT as a primary farm transfer tool. Additional estate planning tools and strategies, like a will and long-term health care planning, would still be necessary.

In previous years, ILTs were sometimes used by farmers to protect assets from Medicaid spend-down requirements. However, at this time in most states, ILTs do not protect assets from Medicaid spend-down unless the 60 month (5-year) lookback period has expired.

For farmers who wish to simultaneously donate to charity, retain an income stream during their lives, reduce income taxes, and reduce estate taxes for heirs at death, a Charitable Remainder Trust is an option to consider.16 This type of trust is a type of Irrevocable Living Trust that transfers the farmer’s assets to a charity while allowing the farmer to both stay on the land and receive income until death. At death, the farmer’s assets then transfer to a charity of choice.17 The value of the donation is deductible from the farmer’s income tax the year the Charitable Remainder Trust is set up and the gift is made.18 19 To assist with the creation of a charitable trust, the Internal Revenue Service provides suggested language on its website. Charitable Remainder Trusts can be used together with other trusts, such as Revocable Living Trusts (RLTs) and Testamentary Trusts.

As with all elements of estate planning and trusts, Irrevocable Living Trusts and Charitable Remainder Trusts must be set up correctly in order to be effective. It’s best to consult with an estate planning attorney who has experience working with farmers and setting up different types of trusts to create a strategic estate plan that meets farm transfer goals.

Advantages Of An ILT

Advantages Of An ILT

- Can provide an income stream and donation to charity (Charitable Remainder Trust)

- May reduce a farmer’s income taxes

- Reduces estate taxes

- Provides assets to beneficiaries immediately

Disadvantages Of An ILT

Disadvantages Of An ILT

- Assets in an ILT are gone for good and cannot be reclaimed

- Farmers can no longer control how assets in an ILT are used

- Farmers will get no income from assets in ILT, in general (unless the ILT is also a Charitable Remainder Trust)

- May require the preparation of additional tax returns, such as a gift tax return and an annual trust income tax return

Testamentary Trusts

A testamentary trust is a trust created by provisions within a will (or under an RLT or ILT). This means the settlor’s (farmer’s) wishes only go into effect upon the farmer’s death. A farmer might prefer the use of a testamentary trust to be able to control the distribution and management of assets even after he or she has passed away. Compared to transfers via a will, transfers via testamentary trust can be more flexible, can include investment and management directions, can have tax advantages, and can provide creditor protection for the heirs. Testamentary trusts created under a will, however, do not avoid the probate process. Note that there are many types of testamentary trusts, and they go by a variety of names, such as A-B Trusts, By-Pass Trusts, and Credit Shelter Trusts.

Advantages Of A Testamentary Trust

Advantages Of A Testamentary Trust

- Lower Upfront Costs. Testamentary trusts are generally less complex and may therefore be less expensive for a lawyer to prepare compared to other types of trusts.

- Asset Protection. Farmers can design a testamentary trust that protects a settlor’s assets from a beneficiary’s wasteful habits, a beneficiary’s creditors, or both.

- Funding. Unlike living trusts, a settlor does not need to fund a testamentary trust during his or her life. A farmer can use will provisions or beneficiary designations to direct assets into the trust at his or her death. For example, life insurance proceeds can be used to fund a testamentary trust.

- Creditor Protection. A testamentary trust may provide a beneficiary with protection from creditors.20

Disadvantages Of A Testamentary Trust

Disadvantages Of A Testamentary Trust

- Irrevocability. Since a testamentary trust only takes effect at the farmer’s (settlor’s) death, its provisions cannot be changed or amended after going into effect unless all of the beneficiaries consent.21 However, courts may modify a trust if: 1) There is a mistake;22 2) Compliance with the trust’s terms are illegal, impossible, or would go against the settlor’s intent, or;23 3) To achieve the settlor’s tax objectives.24

- Probate. Testamentary trusts created under a will must go through the probate process, meaning trust assets will become part of public record and it may be a time-consuming and costly process requiring a court’s continuous oversight. Farm business transitions may be interrupted by the delay caused by the probate process.

How An Attorney Can Help

How An Attorney Can Help

The Attorney’s Role

It’s not an attorney’s job to make decisions for farmers or to set farm transfer goals. Instead, attorneys can provide information about pros and cons of different options, advice about what is common versus unusual, fair versus unfair, etc. Attorneys can help farmers understand the universe of possible farm transfer goals and help narrow down individual options so that farmers can make final decisions.

How An Attorney Can Help With Trusts

- Help select and create effective trusts that meet farm transfer goals.

- Help decide how to strategically use a trust or a combination of different types of trusts as part of an overall estate planning strategy.

- Help assure that farm businesses and farm property will be managed and distributed according to farmers’ wishes.

- Draft the formal paperwork required to effectively fund a trust, including re-titling assets like land or farm equipment.

- Help determine how certain types of trusts might aid or affect long-term health care planning, such as planning for Medicaid eligibility.

Additional Resources

Additional Resources

- Transfer and Estate Planning, University of Minnesota Extension

- Trusts as an Estate Planning Tool, Iowa State University Extension

- Uniform Trust Code (Last Revised/Amended in 2010)

Related Legal Tools

Footnotes:

1. Gary A. Hachfeld, et. al., Establishing A Will, University of Minnesota Extension Estate Planning Series (2016), https://extension.umn.edu/transfer-and-estate-planning/gifting-farm-assets.

2. Gary A. Hachfeld, et. al., Trusts: Definitions, Types & Taxation, University of Minnesota Extension Estate Planning Series (2016), https://extension.umn.edu/transfer-and-estate-planning/gifting-farm-assets.

3. Definition of a Trust, Internal Revenue Service (2016), available at https://www.irs.gov/Charities-&-Non-Profits/Definition-of-a-Trust.

4. See Uniform Trust Code, Section 402, “Requirements for Creation,” https://www.uniformlaws.org/committees/community-home?communitykey=193ff839-7955-4846-8f3c-ce74ac23938d.

5. “Trusts as an Estate Planning Tool,” Iowa State University Extension and Outreach (2014), https://www.extension.iastate.edu/agdm/wholefarm/html/c4-59.html.

6. Gary A. Hachfeld, et. al., Revocable Living Trusts, University of Minnesota Extension Estate Planning Series (2016), https://extension.umn.edu/transfer-and-estate-planning/gifting-farm-assets

7. See Uniform Trust Code, Article 8, “Duties and Powers of A Trustee,” https://www.uniformlaws.org/committees/community-home?communitykey=193ff839-7955-4846-8f3c-ce74ac23938d.

8. Gary A. Hachfeld, et. al., Trusts: Definitions, Types & Taxation, University of Minnesota Extension Estate Planning Series (2016), https://extension.umn.edu/transfer-and-estate-planning/gifting-farm-assets; see also 8-62 Agricultural Law § 62.04 (2015).

9. In this scenario, no income taxes are due on this transfer, the assets are still in the farmer’s control, and they remain as part of the farm estate. Because RLT assets are still part of the farmer’s estate, this significantly lowers estate taxes for heirs by allowing the heirs to receive a stepped up tax basis upon the farmers’ death. See Gary A. Hachfeld, et. al., Trusts: Definitions, Types & Taxation, University of Minnesota Extension Estate Planning Series (2016), https://extension.umn.edu/transfer-and-estate-planning/gifting-farm-assets.

10. Gary A. Hachfeld, et. al., Revocable Living Trusts, University of Minnesota Extension Estate Planning Series (2016), https://extension.umn.edu/transfer-and-estate-planning/gifting-farm-assets.

11. Gary A. Hachfeld, et. al., Revocable Living Trusts, University of Minnesota Extension Estate Planning Series (2016), https://extension.umn.edu/transfer-and-estate-planning/gifting-farm-assets.

12. Guide to Wills and Estates, Fourth Edition: Everything You need to Know about Wills, Estates, Trusts, and Taxes, American Bar Association (2013), https://nypl.overdrive.com/media/1214827; see Christopher R. Dang, et. al, “Planning Ahead: Practical Financial and Estate Planning Considerations,” Haw. B.J., October 2014, at 4,10.

13. Marsha A. Goetting, et. al, “Medicaid and Long-Term Care Costs,” Montana State University Extension (2015), http://store.msuextension.org/publications/FamilyFinancialManagement/MT199511HR.pdf.

14. What is a Miller Trust?, Elder Law Answers, http://www.elderlawanswers.com/what-is-a-miller-trust-14945.

15. Gary A. Hachfeld, et. al., Distribution of Estate Assets, University of Minnesota Extension Estate Planning Series (2016), https://extension.umn.edu/transfer-and-estate-planning/gifting-farm-assets.

16. Understanding Charitable Remainder Trusts, EstatePlanning.com, https://www.estateplanning.com/Understanding-Charitable-Remainder-Trusts/.

17. “Trusts as an Estate Planning Tool,” Iowa State University Extension and Outreach (2014), https://www.extension.iastate.edu/agdm/wholefarm/html/c4-59.html .

18. Gary A. Hachfeld, et. al., Trusts: Definitions, Types & Taxation, University of Minnesota Extension Estate Planning Series (2016), https://extension.umn.edu/transfer-and-estate-planning/gifting-farm-assets.

19. See Uniform Trust Code, Section 405, “Charitable Purposes; Enforcement,” https://www.uniformlaws.org/committees/community-home?communitykey=193ff839-7955-4846-8f3c-ce74ac23938d.

20. “Two Types of Trusts: Which Protect Against Creditors?,” EstatePlanning.com (2013), https://www.estateplanning.com/which-type-of-trust-protect-against-creditors/.

21. See Uniform Trust Code, Section 411, “Modification or Termination of Noncharitable Irrevocable Trust By Consent,” https://www.uniformlaws.org/committees/community-home?communitykey=193ff839-7955-4846-8f3c-ce74ac23938d.

22. See Uniform Trust Code, Section 415, “Reformation to Correct Mistakes,” https://www.uniformlaws.org/committees/community-home?communitykey=193ff839-7955-4846-8f3c-ce74ac23938d.

23. See Uniform Trust Code, Section 415, “Reformation to Correct Mistakes,” https://www.uniformlaws.org/committees/community-home?communitykey=193ff839-7955-4846-8f3c-ce74ac23938d.

24. See Uniform Trust Code, Section 416, “Modification to Achieve Settlor’s Tax Objectives,” https://www.uniformlaws.org/committees/community-home?communitykey=193ff839-7955-4846-8f3c-ce74ac23938d.

The Center for Agriculture and Food Systems is an initiative of Vermont Law School, and this toolkit provides general legal information for educational purposes only. It is not meant to substitute, and should not be relied upon, for legal advice. Each farmer’s circumstances are unique, state laws vary, and the information contained herein is specific to the time of publication. Accordingly, for legal advice, please consult an attorney licensed in your state.